Peter Beard Biography Chronicles Life of Montauk's Wildest Artist

More than two years after artist and legendary Montauk figure Peter Beard wandered off and met his end in the dense and tangled brush of Camp Hero State Park, author Graham Boynton’s new biography presents him as the imperfect and utterly irresistible character he was, even as he remains something of an enigma when the book’s final pages turn.

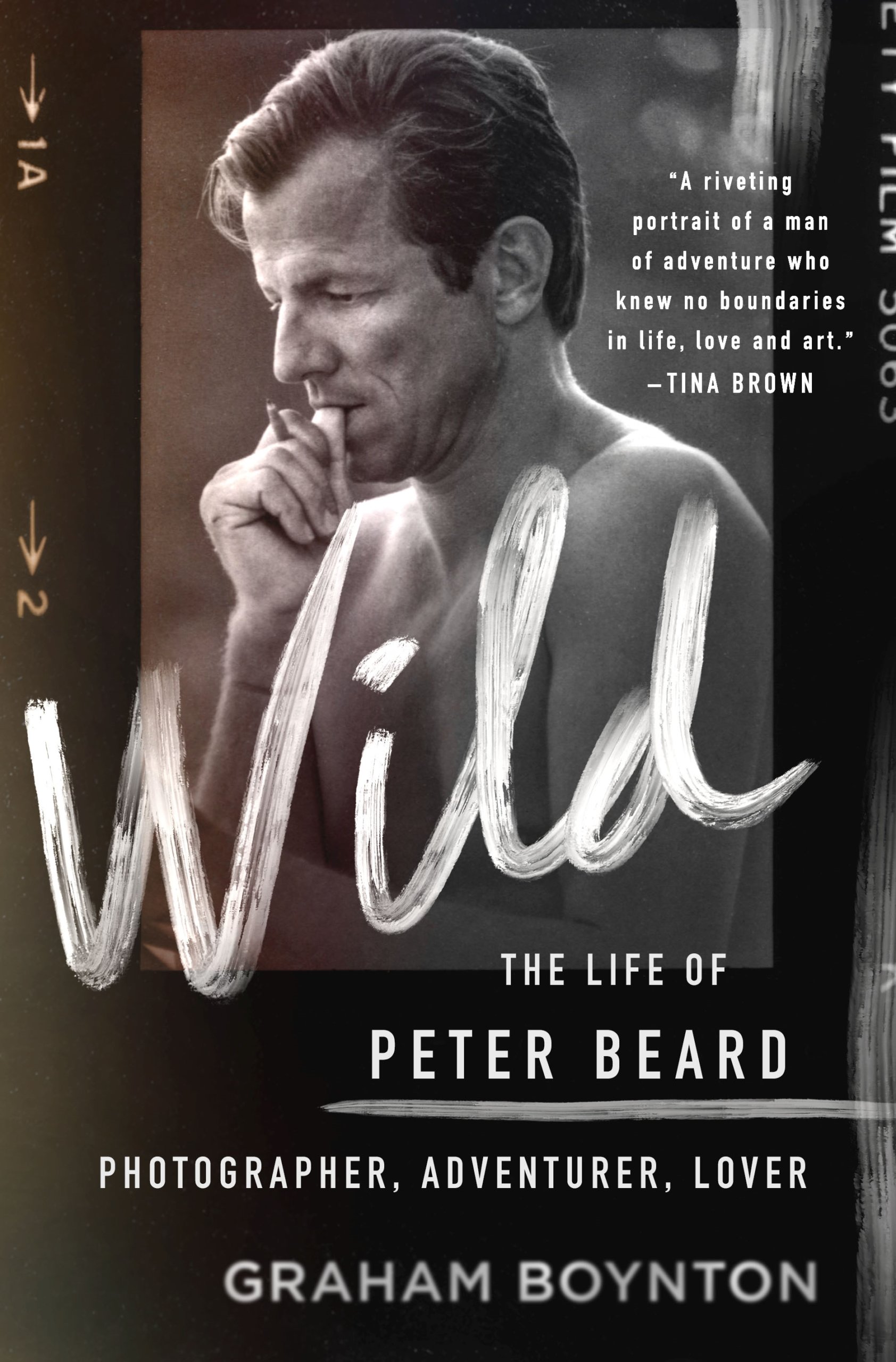

Published by St. Martin’s Press on October 11, author Graham Boynton’s Wild: The Life of Peter Beard, Photographer, Adventurer, Lover offers as clear a picture of Beard as can be had, perhaps.

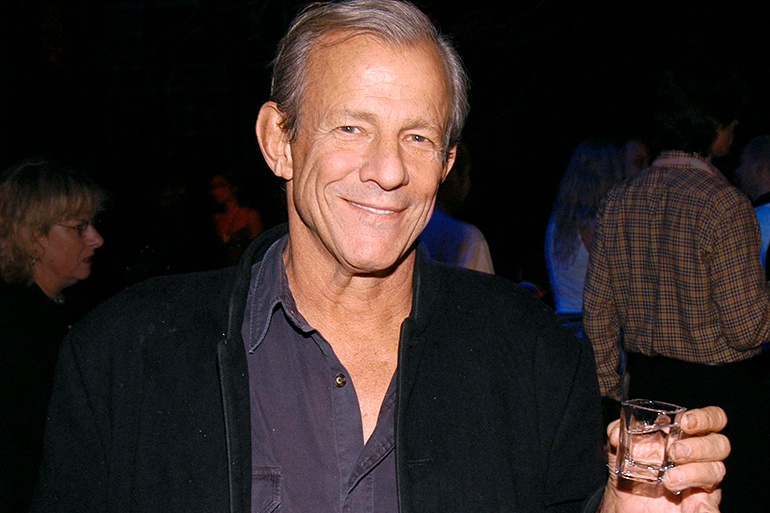

The outrageously handsome and magnetic bon vivant was a world-famous adventurer and environmentalist who made women swoon and men want to be him. He hobnobbed with celebrities like Andy Warhol, Francis Bacon, Jackie Onassis, Truman Capote, Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones.

He always had a young beauty on his arm and spent the bulk of his days and nights “pleasantly pixelated” as he’s quoted saying in the book, on a list of drugs that started with booze and marijuana, often included cocaine and could extend all the way to crack. Yet few would ever see Beard lose control.

While Boynton’s book talks about all these inescapable aspects of Peter Beard, the author understands that his subject was, at his core, an artist above all things. It was, as Boynton writes, his “raison d’etre.” And he makes an effort to examine Beard’s powerful work featuring collaged photographs taken in the African bush and the beaches of Montauk, often painted with blood, scrawled with notes in pen and ink, and festooned with bits of detritus and ephemera he collected during his travels.

What is its significance and value in the broader art world, and where does Beard’s legacy stand in the pantheon of geniuses who came before him, and those who will follow? The author doesn’t quite find an answer, but this book will help inform anyone examining these questions further.

The Wild Life of Peter Beard

Wild begins with Beard’s death in 2020, when the 82-year-old, suffering with dementia, walked into the Montauk woods and vanished, his body mysteriously eluding discovery during a massive search that employed helicopters and dogs, until three weeks later, when a friend found him in dense underbrush, laying in a stream just 500 meters from his home. It was a dramatic end to a life filled with drama, and it was, as Boynton contends, “probably how he would have wished to end his life.”

Boynton, who had a decades-long friendship with Beard, shares his own experiences with the artist and digs into his life and loves, beginning with an explanation of his monied family lineage and stories of an incorrigible child who was never afraid to fight or take risks.

In one recollection, Beard’s lifelong friend Tony Hoyt recalls how he pushed his way into an ice hockey goal with no protective equipment and encouraged Hoyt and his fellow players to fire shots at him, which they did. “That was what he was like,” Hoyt said. “Brave and completely crazy.”

Of course, Beard’s propensity for risk and danger found much greater extremes, especially during his time in Africa, a place that would inspire and then define him in the decades ahead. He came to the continent as a hunter, but soon found himself advocating for the wildlife and the land and railing against poachers in his now classic book The End of the Game.

Wild recounts his run-ins with man and animal in Africa, including the 1996 elephant attack that very nearly killed him. That particular incident is already well cemented into Beard’s legend, as it should be, but the book offers up some lesser-known adventures, and some not-so-flattering tales that show a man who could be cruel and contradictory.

The book also focuses on Beard’s prolific love life, which had an ever-expanding list of conquests that was never interrupted despite being married three times — first to socialite Mary “Minnie” Olivia Cochran Cushing in 1967, followed by model Cheryl Tiegs from 1982–1986, and, most importantly, his litigious and long-suffering third wife Nejma. The latter, who he married shortly after divorcing Tiegs, is the mother of Beard’s daughter Zara and remained with him until the end, despite years of infidelity and so-called bad behavior.

Perhaps Beard’s most important partnership, drug-fueled as it may have been, was with The Time Is Always Now gallerist Peter Tunney, who did much to bring the artist’s work to the fore in the 1990s, upping his prices significantly and setting him up for his most prolific period working in the bowels of the Broome Street gallery.

As Boynton tells it, and those who were there to witness it would agree, this was a particularly magical and fertile period for the artist, though he regularly used his works as currency to trade in payment of a bill or a bar tab, or he simply gave them away to friends, lovers, even near strangers who caught him in the right mood.

In an effort to keep Beard from the drugs and women, and friends who she saw as users, according to Wild, Nejma began to keep her husband away from all who came calling. At the same time, she made efforts to reclaim work he had given away, or sold too cheaply, often at the expense of friendships. Understandable, some might say, but to those who knew and loved the man, it also felt anathema to his nature.

The author clearly harbors some resentments toward Nejma, as a number of Beard’s friends did, and he spends time explaining how she caged the free-spirited creature in the twilight of his life, separating him from the friends, beautiful young women and random characters who once came and went from their home atop the Montauk bluffs. Some of them may have visited with a spliff or bag of cocaine at the ready (possibly at Beard’s insistence), but most were probably just eager to sit on a log, talk art and simply be in his presence.

Beard was a man who could make friends, admirers, acquaintances and lovers feel absolutely blessed to be in his orbit, yet this freewheeling, magnanimous nature also seemed to frustrate and enrage his own family to the point where they sequestered him away from many of the people who loved him.

But, Boynton writes, Beard seemed to go along with it, discarding friends in a way that to the author felt “sociopathic.” Yet few harbored resentments against Beard. Somehow, the author says nearly all of Beard’s lovers retained friendships with him after their passions dimmed, and they rarely carried ill will.

Wild is a the first full chronicle of Peter Beard’s life since his death, and it does an excellent job of putting together all the scattered pieces, and a bit of blood, to tell the truth of the man and his art which will surely endure.