A Clandestine Visit to Steinbeck's Writing Studio

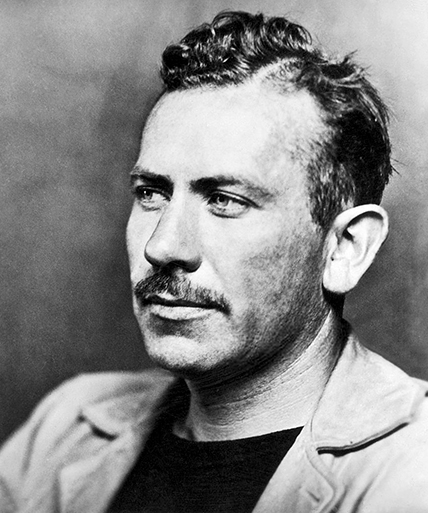

Here I am at 2 a.m. writing this article seated in a chair at the desk inside John Steinbeck’s waterfront writing studio, a six-sided structure this celebrated author built with his own hands shortly after moving from California to Sag Harbor in 1955.

I am supposedly not allowed to be here. But it’s the middle of the night, and Oliver Peterson, the managing editor of Dan’sPapers.com, quietly rowed me across the bay to Steinbeck’s old property. The great man’s long gone, of course. But his boat dock, his house, and, across the lawn, his studio, built to resemble a lighthouse, remain. Peterson, sitting in the rowboat, waits. If I have to make a quick getaway, he’s ready.

I’m here because I’m trying to write a story about the upcoming Hamptons International Film Festival for Dan’s Papers and I’m having writer’s block. Peterson suggested I might get inspired if I tried to write it from the great man’s studio, so here I am.

At this hour, both the house and studio are dark. The property’s for sale. And I’m not turning on any light. Hopefully, I’ll think of something.

Inside the studio, there is lots of stuff that Steinbeck supposedly used to write his great novels. The desk has an old worn blotter covering on it. His Remington typewriter sits atop it. Ready to go. There’s an old, ripped Oriental carpet on the floor. The chair, which swivels around, squeaks. There’s a bookshelf along one wall. A clock on another wall. And pinned to still another wall are some notes I guess he wrote. I’ve set my laptop next to Steinbeck’s Remington. The view out the window is of the bay.

Steinbeck was here in 1962 when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. He wrote The Winter of Our Discontent here. He wrote Travels with Charley, a work of nonfiction about a car trip he took from Sag Harbor to places all around the country accompanied by his dog Charley, here. His most famous book, The Grapes of Wrath, was not written here. He wrote it during the Great Depression, about the terribly hard life experienced by the farmers and fishermen in and around Salinas and Monterey, California.

As he often said later on, he moved to the fishing town of Sag Harbor with his wife Elaine because it reminded him of Monterey. He passed away in 1968 at the age of 66.

Well, here’s what I wrote before I got here:

“This weekend is the thirtieth running of the Hamptons International Film Festival, where hundreds of producers, screenwriters, distributors, producers, directors, actors and composers assemble to meet with everybody else to mingle, do deals, find new scripts, and watch films, some of which, after the 10 days of the festival, will win awards.”

And that’s as far as I got. The word “running” sounds too much like a horse race. And the word “deals” sounds too under the table. There’s got to be more to this.

Outside, I can hear the crickets chirping. I can see the fireflies and the stars. The night is clear. And when the wind stirs the bay, sparkling ripples slide across its surface. Occasionally, there is a slap down at the dock. Peterson’s lowered an oar into the water.

Aha! It’s hit me. I start typing.

If people in the film industry who are here for the festival ever wonder if what they do is important in the scheme of things, all they have to do is look up into the sky one night out here and imagine, or even see, way off into space, an explosion in the heavens that now has resulted from an idea first conceived by a screenwriter.

The screenwriter Bruce Joel Rubin had been hired to write the script for a 1998 film called Deep Impact. In the movie, a meteor is headed for the Earth. If it hits, everybody will die. But maybe, its course could be deflected if the United States fires a rocket at it. The rocket would hit the meteor, explode, and the meteor could veer off and miss. It was at least worth a try.

Steven Spielberg, who lives in East Hampton, was the executive producer of this film. And in the climactic scene in the movie, the effort would fail and a great 300-foot tidal wave would leap across a beach in Amagansett and inundate the entire Earth, with the two leading stars in the movie, Robert Duvall and Tea Leoni, playing estranged father and daughter, would forgive one another just before the catastrophe.

A casting call for extras was posted on the wall in the Amagansett fire house, advertisements in Dan’s Papers appeared, and a crowd came to the firehouse on the appointed day to apply. I applied. Who wouldn’t want to be in a movie? But I was not chosen.

The final scene was indeed filmed on the beach, but much of it wound up on the cutting room floor because computer-generated imagery (CGI) effects produced a better catastrophe. But there you are.

The following month, the movie Armageddon was released with essentially the same plot. It did better than Deep Impact. But that did not change the fact that the originator of the meteor-headed-toward Earth story idea was still Bruce Joel Rubin, the screenwriter for Deep Impact.

Well, guess what? On September 26, in real life, NASA scientists fired off a rocket at a far-off meteor heading our way to see if the resulting explosion could send it skittering off in another direction. Even though the meteor posed no danger to us, American taxpayers nevertheless paid more than $300 million for this to happen. The explosion, I believe, would take place during the festival.

Well, there you are. Moviemakers make things happen. And moviemakers matter.

Ooops. A light just went on at the main house. I’m out the door and in the rowboat. Peterson, get us out of here.