Shinnecock Voices: Waves, Coping with a Lost Grandparent

People say grief comes in waves. I’ve been learning how to ride those waves for six months now, adjusting to what life looks like with one less grandparent.

Sometimes the waves are small, so small that it feels like a pebble was dropped into a puddle, but there are days when their height doubles and doubles until it feels like a tsunami. But between the pebble ripples and tsunamis, there are days I feel like the tide is creeping up and up and up.

You ever go to the beach in the morning and set up close to the shore, and you know you’ll have to move back eventually but you keep putting it off? And before you know it, the tide has crept up to where you are.

The waves reach for your towel and you have to rush to move your chair and your umbrella and your bag. You knew the waves would get you, but you didn’t want to think about them. Grief is kind of like that. Inevitable.

Sometimes it’s more like when Superstorm Sandy hit. The wind had died down enough for my dad to feel OK walking across our backyard, under the big oak and cherry trees.

He made his way to our stairs that lead down to the water. He stood there in the darkness and even though he couldn’t really see, he could tell the water had risen about seven feet above the steps and was right below the wooden deck.

The water was high, so so high, higher than it had ever been in his life. It didn’t go over the bank and into our yard, but it was close. The tide was right there, right under the deck, right there under his feet. Sometimes grief feels just like that. Looming.

Early on in the summer, Poppa drove into our yard in his Kawasaki utility vehicle — he was always more of a John Deere man, but had been driving a Kawasaki for a while. I had gotten back from college a few days prior and hadn’t made my way over to visit him just yet.

I was in bed and could hear the sound of him driving over the gravel, but I didn’t get up.

I didn’t run downstairs and poke my head out the back door and say, “Hi.” I didn’t tell him how my semester went or what I was most excited about for the summer. I stayed in bed and told myself I’d go talk with him another day.

My dad was on a business call but could see Poppa from the sliding glass windows of our dining room. Poppa drove through the yard to look at the water, then turned around and left.

A couple days later, I saw him in a hospital bed. I held his hand as our tears said what neither one of us could find the words to say.

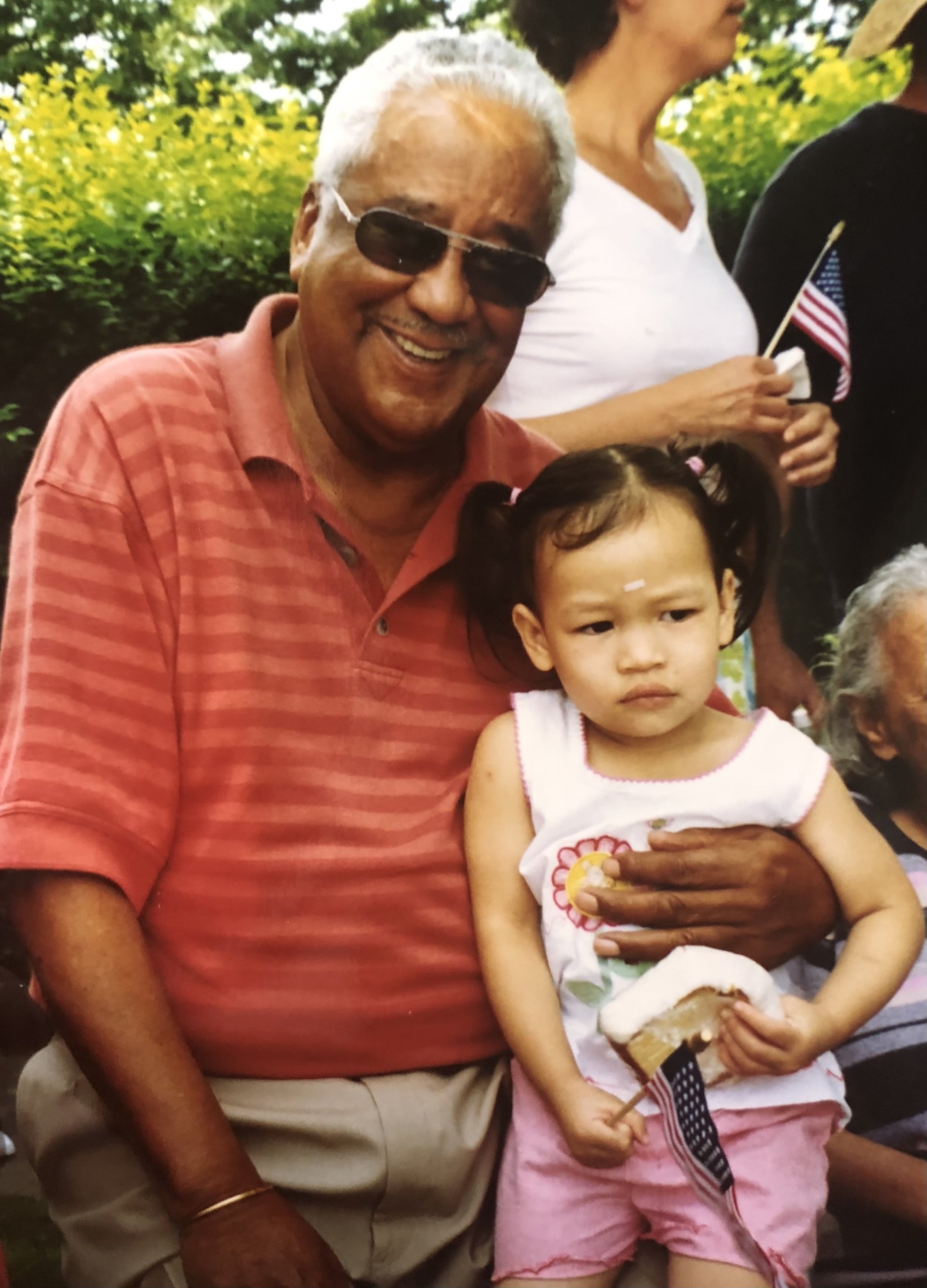

Poppa would give me something every time I saw him — whatever knickknack he had on his side table or a few bills from his wallet or a story. Whatever he slipped into my hands and into my heart was always accompanied by a hug and a kiss.

The day he passed, we got home from the hospital and my mama found a feather at the end of our driveway. I’m sorry I don’t know where that silver bracelet with the painted red heart is. I’m sorry I don’t know where that carved wooden figure is. I’m most sorry that I didn’t jump out of bed to go see him that day he drove into the yard. But that feather made me feel like it was all OK.

A few days after his funeral, when the out-of-town relatives had left and my house was empty again, I sat quietly in the living room. It was my first true moment alone in nearly a week. It was sunny with a slight breeze, a perfect early summer day.

I heard someone coming down the driveway, so I went over to the back door to take a peek. And for the smallest fraction of a millisecond, I expected to see my grandfather pulling in. It felt like a tsunami swallowed me whole.

The first time I dreamt of him was a couple days after that. He sat in my yard and talked with me and my sisters. There was a bright light behind him. He asked us to come take a ride with him. I woke up and surfed that wave with a smile.

This past summer I lived by myself for the first time. My first night alone, I woke up at 3 a.m. and swore I saw him across the room for the smallest fraction of a millisecond. “Hi, Poppa,” I whispered. The tide crept up.

There have been times when the waves have made their way into my dreams. I may see my grandfather and become painfully aware that I’m dreaming, that I’ll wake up and he won’t physically be with me. Instead of reaching for him, I pull back and start running from the tsunami. I wake up underwater some days.

It’s been six months and I’m adjusting to the tide always being high. I know the water will continue to pool around my ankles on holidays and on birthdays and on random days, too. And I’ll welcome any wave he sends my way and say, “Hi, Poppa.”

Asia Cofield is a citizen of the Shinnecock Nation. She’s currently a senior at Brown University pursuing a B.A. in Literary Arts with Honors.

“Shinnecock Voices” is a monthly column in which citizens of the Shinnecock Nation share stories and opinions and discuss the projects and campaigns they’re working on, to allow readers an inside view into their incredible community.