SANS Preservation Pushback: Sag Harbor Protection of Historic Black Beach Community Stirs Debate

Influential poet Langston Hughes, who was dubbed the leader of the Harlem Renaissance. Former Manhattan Borough President Edward Dudley, who was the first African-American ambassador to the United States. Former secretary of the NAACP William Pickens. These were among the most well-known Black leaders who either summered or lived in one of three Sag Harbor communities where minorities flocked for respite during the era of segregation.

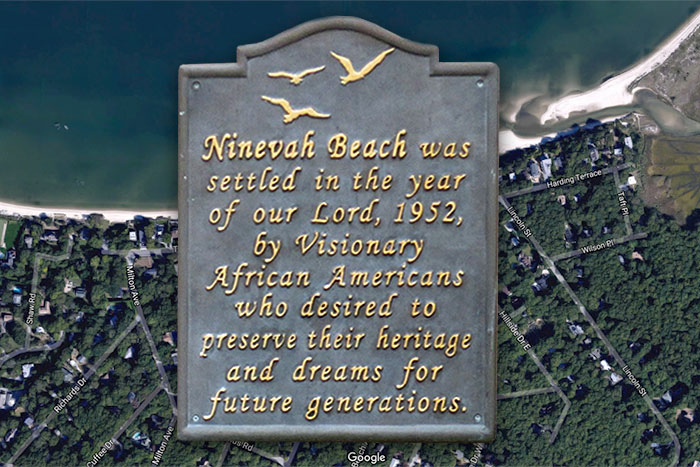

In an effort to preserve this rare community, the Sag Harbor Village Board recently passed a law enacting the Historic Black Beach Communities Overlay District. It includes Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest, and Ninevah Beach Subdivisions Historic District — neighborhoods, known locally as SANS for short, which in 2019 were added to the New York State Register of Historic Places and the National Register of Historic Places.

Preserving SANS

“SANS is of national importance,” Renee V.H. Simons, president of SANS Sag Harbor, a nonprofit that advocates for the area’s preservation, said before the village board unanimously voted to establish the district in December. “When you walk through the SANS area, you are walking through a living national historic site. … It is not just about a people’s social life and a generation. It is about the physical nature of how a planned community developed.”

SANS formed at around the same time that Levittown — widely considered America’s first suburb — was built in the 1940s for soldiers returning from World War II, but with a covenant on deeds that restricted homeowners from selling their property to minorities.

In response to Jim Crow-era legalized segregation, Black residents formed SANS, where they could enjoy a slice of summer in the Hamptons without facing prejudice — and it’s one of but a handful of such communities that still exist nationwide.

“SANS is probably one of the biggest phenomena and historically important occurrences in this village,” Simons said of the community that comprises about 300 homes, or around a third of the village residences. “We talk about whaling, we talk about the captains. We should be talking about what happened in SANS. … There are only five of these around the country. There used to be 100.”

But like anything else involving modern-day real estate on the East End — or anywhere on Long Island or in New York, for that matter — the plan has stirred debate from those in the community concerned about how it may inhibit homeowners’ freedom to maximize their investment by renovating or rebuilding.

Unintended Consequences of Preserving SANS

Azurest Property Owners Association President Steven Williams, who also chairs the Village of Sag Harbor Board of Historic Preservation and Architectural Review, fears the good intentions will have the unintended consequence of shackling the community with cumbersome zoning rules restricting residents to expensive, antiquated building materials and prohibiting redevelopment.

“This would be a restraint on our … property rights,” Williams told the village board, noting that homes in historic districts are more expensive than a regular home to maintain. “That’s what we’re talking about: Making a museum of old, no longer functional houses, versus allowing the founders, their children, their grandchildren and the new members to thrive in the community they created and to manipulate their property in such a way that it serves their highest and best use.”

The village resolution notes that the area does not have an overarching architectural style.

“Initially, the homes were best characterized as modest bungalows, although there has long been a wide diversity in home style and grandeur,” it states. “What defined the look and feel of the three communities was not attributable to a particular architectural design or style. Instead, it was the sense of community and the close, familial relationship of the residents, and the rustic quality of size-appropriate homes set within treed lots unadorned by sidewalks or curbs.”

The resolution notes that the area is now at risk of gentrification.

“Over time, the community evolved, and the diversity in homes and homeowners increased. Rapidly increasing home values led to two important and conflicting developments,” the resolution adds. “Long term African American homeowners could transfer, inter-generationally, the significant equity in their homes — an option long suppressed through policies like redlining and predatory lending. On the flip side, speculators and investors insensitive to culture and norms have become increasingly active in the communities — resulting in development approvals for homes inconsistent with the character of the communities.”

In an effort to keep the charm in place, the overlay district limits structures to no more than 4,000 square feet — even if the lot has been merged with a neighboring property — no addition of sidewalks, bans impervious driveways and limits to three the number of accessory buildings or structures on a property. It also requires that photo or video evidence of a violation of an overlay district provision should trigger a village investigation, though so far it has been all quiet in SANS.

“We have not received any new complaints in the area since the adoption of the legislation,” said Village of Sag Harbor Senior Building Inspector Christopher Talbot.

Village officials added that the new district runs concurrent with its role as a certified local government (CLG) tasked with administering SANS’ federal status as a historic place. Sag Harbor leaders promised advocates to continue efforts to inventory properties that may be added to the district.

“We will work with you on the CLG process as we promised to do,” said Sag Harbor Mayor James Larocca.

Among historic places in SANS? The porch of Pickens’ Ninevah home, where Hughes and other prominent writers recited poetry. The location is a stop on the Literary Sag Harbor Walking Tour.