Art Cooley's Crusade Against DDT Made Him a Long Island Champion of the Earth

Art Cooley’s Crusade Against DDT Made Him a Long Island Champion of the Earth

Seventy years ago, all over the world, malaria was killing hundreds of thousands of people — until a powerful new weapon practically wiped out the mosquito-borne disease. Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) was an organochlorine insecticide that was hailed as a miracle because it was also effective against typhus, body lice, and bubonic plague. U.S. farmers seized on it to protect their food crops from hungry insects. This was truly a wonder chemical: It was effective, cheap, and lasted a long time — at least three generations.

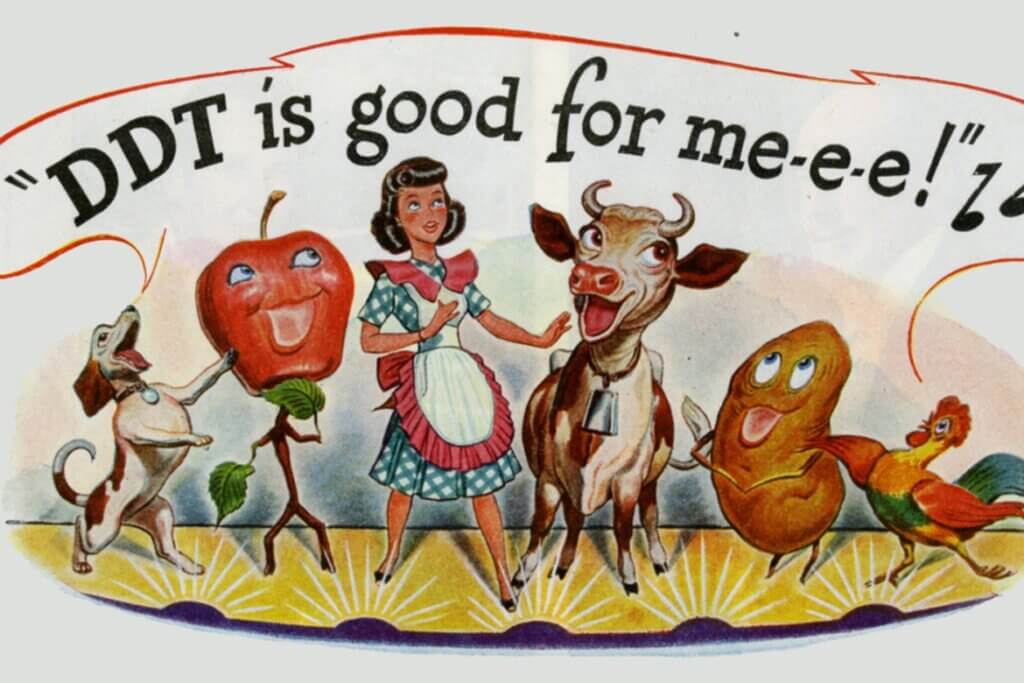

Locally, starting in the 1940s and continuing for decades, the Suffolk County Mosquito Control Commission sprayed DDT in salt marshes. But in 1945, controversy arose when Time Magazine published an article called “DDT Dangers.” Despite the red flags raised by many researchers, society continued to embrace the use of DDT and other similar insecticides.

But then Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published, in 1962; some say the blockbuster book spearheaded the modern environmental movement. It was a rallying cry to ban DDT and end “the misuse of chemical pesticides that she claimed were degrading the environment on an unprecedented scale,” reported the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

And then Art Cooley took notice.

NOTHING IS IMPOSSIBLE

Who was this concerned citizen? Born in 1934 in Southampton and raised in Quogue, the native Long Islander taught biology at Bellport High School in Brookhaven Hamlet in the 1960s. As a naturalist, expedition leader, and bird watcher, he was most passionate about local issues: salt water marsh preservation, farm runoff, waste dumps, and groundwater contamination. He and others took action when they realized that something was decimating the local eagle and osprey populations. As he later observed, “We knew DDT was damaging the eggshells of birds, preventing chicks and eaglets from hatching.”

At the time, there were no federal regulatory agencies guarding planet Earth, no Earth Day, no Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), no Environmental Defense Fund. Americans had a love-hate relationship with pesticides, as described by Clay Cansler, editorial director of the Science History Institute: “Vacuum cleaner attachments, such as the Whirl-A-Way Insector, gassed moths and larvae as the machine swept the carpet. And with the Arnold garden-hose sprayer you could battle pests with DDT or lead arsenate (cheerfully marketed as Arsen-O-Spray) while watering the tomatoes.”

But the science was clear. According to the National Pesticide Information Center, DDT persists in the environment, accumulates in fatty tissues, and can cause adverse health effects on humans and wildlife.

LIVING ROOM CRUSADERS

Starting small, meeting in Cooley’s East Patchogue living room and in the homes of other environmental crusaders in 1965, a determined group of activists voted to use the power of the law to get the toxic pesticides DDT and dieldrin banned locally and nationwide. Armed with his concern for nature, Cooley told the La Jolla Light, “When I was in eighth grade, our class motto was: ‘Nothing is impossible but some things just take longer.’”

It was an uphill fight, bookended by polar opposites: On the pros side, chemicals such as DDT helped save hundreds of thousands of lives in areas beset by malaria and other insect-borne diseases; but in the cons column, the long-lived chemicals threatened human and animal health.

“The elimination of DDT paved the way for the return of the brown pelicans, peregrine falcons, bald eagles and ospreys, to name a few,” Art Cooley said.

The goal of Cooley’s group was to go after DDT. They made a motion to sue the state of Michigan, then they sued the state of Wisconsin. Both states banned DDT use. In 1966, they filed a class action lawsuit which forced the Suffolk County Mosquito Control Commission to stop using DDT in salt marshes. And in 1967, Cooley, Charlie Wurster, and Dennis Puleston co-founded the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). Its mission: Preserve the natural systems on which all life depends.

According to the Environmental Defense Fund website, Cooley was the self-described “eclectic optimist” who led the group. Someone told co-founder Wurster that Cooley “… could get a group of people excited about a blade of grass.” Cooley’s students said his passion and enthusiasm were contagious. Others described his warmth and charisma that “helped bring people together in common cause,” said EDF’s longtime president, Fred Krupp.

The notion of protecting nature gained traction: in 1970, Earth Day (April 22) was founded; the next year, New York State banned the use of DDT; and in 1972, the EPA banned the use of DDT nationwide, an action that evolved in part from earlier lawsuits by the EDF and the Sierra Club.

The hard-won victories Cooley shepherded helped establish the right of ordinary citizens to sue the government to protect human and animal health and the environment. As he told the La Jolla Light, “the elimination of DDT paved the way for the return of the brown pelicans, peregrine falcons, bald eagles and ospreys, to name a few. Along the way we helped to get lead out of gasoline and paints, to establish a cap-and-trade program for sulfur dioxide to control acid rain, and through the Montreal Protocol to reduce gasses that caused the ozone hole.”

Cooley died in 2022 at age 87.