Hamptons Subway Will Open Memorial Day Weekend

As most people know, the single most spectacular real estate development ever attempted on the East End was that of Carl G. Fisher. In the mid-1920s, he bought the entire peninsula of Montauk, nearly 12,000 acres in all, and during the years between 1925 and 1929 began to build a great resort city in that community.

The centerpiece of it, built on the downtown plaza he created in a field, was the seven-story building that continues to dominate this community to this day.

He also built a polo field, a yacht club, the Montauk Bathing Casino, a boardwalk and swim club, a tennis court with a glass ceiling — now the Montauk Playhouse — and a 250-room hotel high on a hill that still stands as the Montauk Manor.

He additionally built Montauk Harbor, the entire network of roads in downtown Montauk, including pink sidewalks which survive in many areas, half a dozen downtown commercial buildings, two churches and an automobile racetrack. He imported sheep as well and built a village at Shepherd’s Neck, which is still in existence.

His intention from the get-go was to build a resort similar to the one he had built in the early 1920s in Miami Beach. Among other things, he had recently been married for the third time, to an 18-year-old socialite named Jane. These were heady times for millionaire Carl Fisher.

What has never been known until now is that while Fisher and some of his wealthy friends were building Montauk (it failed in the crash of ’29), there was a lesser-known and very shady builder by the name of Ivan Kratz who had plans to make a fortune as the unofficial transportation commissioner for the Fisher operation.

Kratz, between 1920 and 1925, had made millions by building a part of the New York City Subway System. His work was good, but the way he went about securing contracts was crooked. By 1919, offering up a whole slew of bribes to New York City officials, he had bid high but nevertheless got the contract to build the Lexington Avenue Subway. By overcharging for materials and then paying notoriously low salaries to his workmen, he made huge amounts of money on both ends.

By 1924, however, Kratz was under investigation as part of the Teapot Dome bribery scandal. Amazingly, when it came time to look for the money Kratz had stolen — he was by this time the owner of a large oceanfront estate in Southampton — it all came up empty. Where had the money gone?

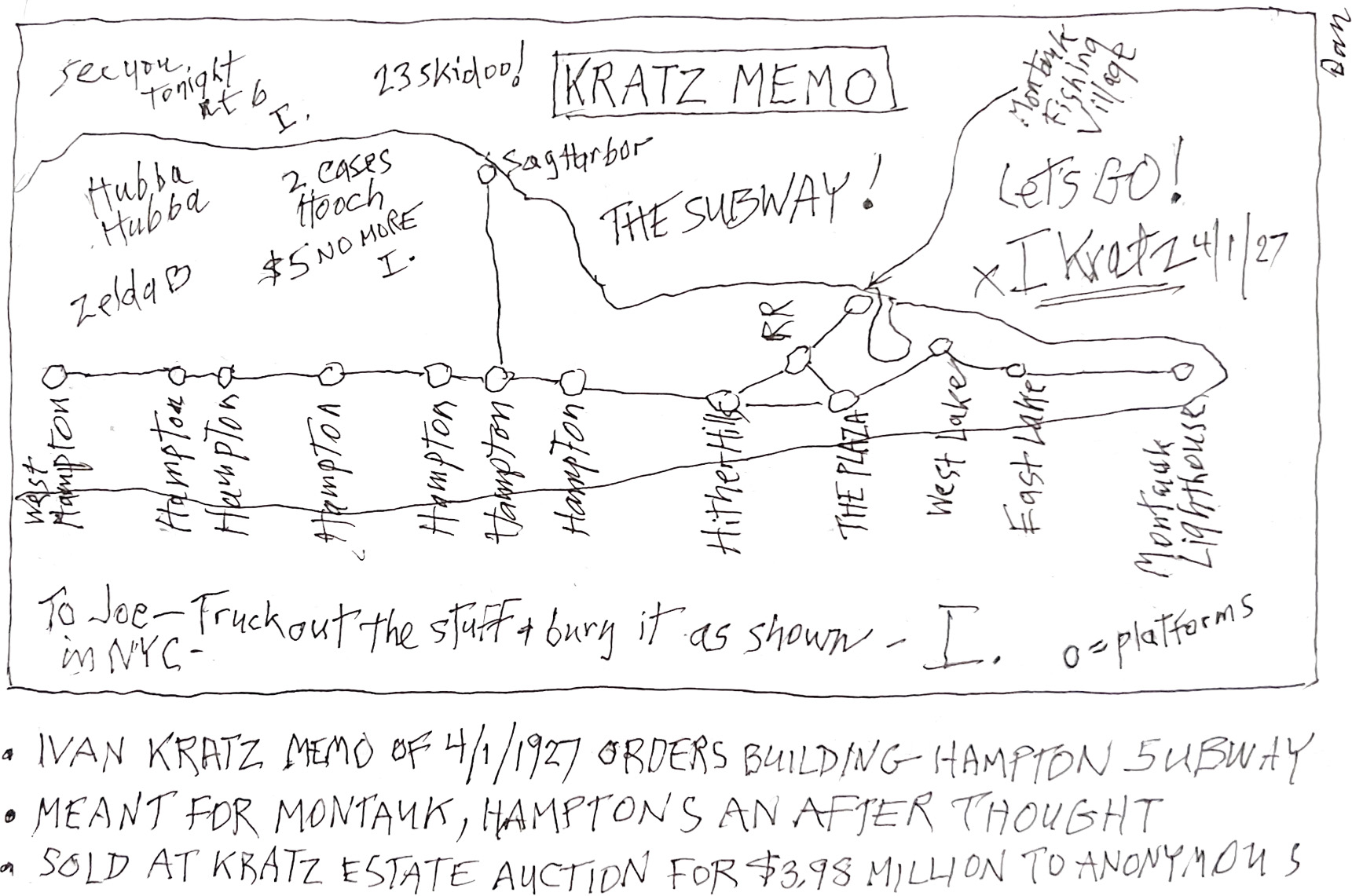

After Kratz’s death, auctioneers selling the contents of his estate came upon an extraordinary document. Copies of it were turned over to the Town of Southampton, the Town of East Hampton and the New York State Department of Transportation (DOT).

It turned out that Kratz, between 1925 and 1927, stole huge amounts of building material intended for the Lexington Avenue Subway system he was building. As the feds closed in, he had it secretly transported to an underground warehouse in Montauk, where, subsequently, he decided to use it to construct a vast underground subway system. Nobody would be the wiser about where this material had come from.

According to the map, it would be named the Hamptons Subway. From its main terminus under the open plaza in downtown Montauk, it would feature trackage through tunnels to underground stations in Napeague, Amagansett, East Hampton, Bridgehampton, Southampton, Quogue, Sag Harbor and Westhampton Beach, with 17 stations in all.

“At first,” said Charles Winston of the DOT, “we thought that the subway map that had turned up at the auction was some kind of joke.”

But then, reading the subway map and below it a description of vast amounts of subway building material, a search got underway to find Kratz’s underground warehouse.

On day two of that search, separately, a group of federal workmen digging on a superfund site in Sag Harbor behind the post office struck some sort of underground concrete dome with their shovels. Breaking through, the workmen found themselves in the ceiling of a subway station.

There were twin platforms, two sets of rails including a third rail that went down into some dark tunnels, a ticket booth, turnstiles and a flight of stairs that went up to a steel Bilco door that had been covered up by grass. The Sag Harbor station for the G Train.

“It’s all in place,” Winston said at yesterday’s press conference. His eyes welled up with tears. “The whole thing. Seventy miles of tunnels. We’ve been through it from end to end. It has the same white ceramic tiles on the walls that are in the New York Subway system. The names of all the stations are in blue tiles. The track gauge is also from the New York Subway. It’s amazing. And it’s the answer to our prayers. The transportation nightmare in the Hamptons is over.”

No station was built in Hampton Bays, however.

“We don’t know why,” Winston continued. “Members of the Kratz family say that their grandfather once complained about a yacht he bought from a marina owner in Hampton Bays that sprang a leak and sank. That, we think, might be as good a reason as any. We will build a Hampton Bays station.”

A reporter asked Winston where all the money will come from.

“Governor Hochul this morning created a Hamptons Transportation Authority, with a base funding of $50 million. We are dipping into it already.”

A reporter asked if Fisher himself, who had an excellent and above-board reputation, had been involved in this.

“We have dug deep into the Fisher archives,” Winston continued. “Apparently, he thought Kratz was some kind of drainage subcontractor. He seems to have been aware of it, but that was about it. He was a big picture sort of guy.”

“Did Kratz get away with all of this?”

“No. He was arrested for bribery and fraud, convicted and sent to prison. He died in prison.”

“Any idea when the South Fork Subway will become operational?”

“It just needs a good vacuuming,” he said. “It will open for Memorial Day Weekend. And we are building a statue of Mr. Kratz for the Southampton platform. People need to know about this special gentleman.”