Shinnecock Voices: 6 Shinnecock Women Grow Kelp to Fight Climate Change & Save Shinnecock Bay

Six Shinnecock women regularly rise early, pull on waders and gloves, and head out into Shinnecock Bay year-round, in what has become a salvation practice for the water. It’s no surprise that the multi-generational collective, all enrolled members of the Shinnecock Indian Nation (and cousins to this writer) have made ancestral kelp farming practices a big part of their daily life.

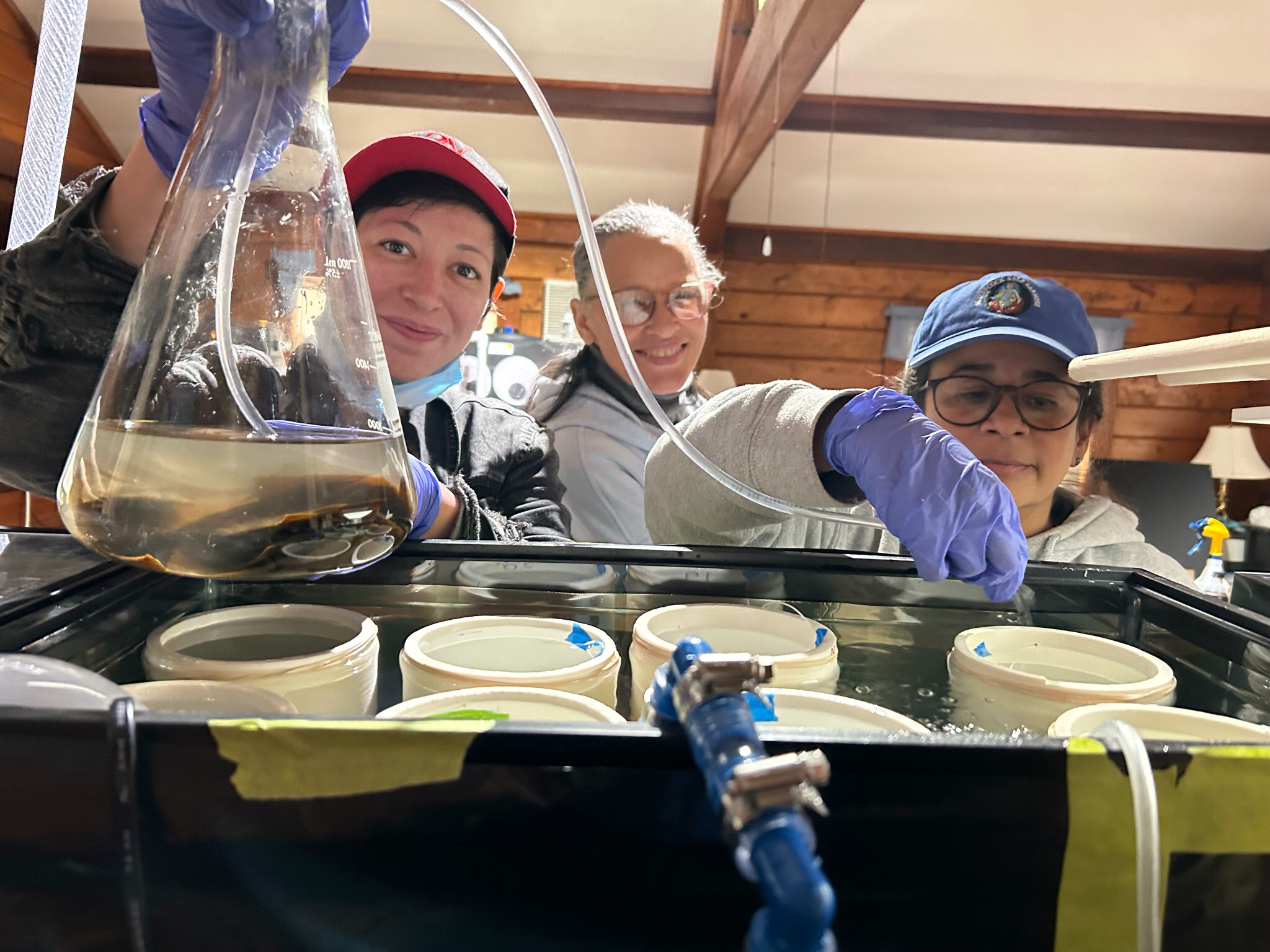

Tela Troge, Donna Collins-Smith, Danielle Hopson Begun, Waban Tarrant, Rebecca Genia and Darlene Troge, Tela Troge’s mother, make up the Shinnecock Kelp Farmers. Part of their goal in using biodiverse and traditional farming practices is to clean the area waters through kelp farming and to see the return of traditionally captured fish for consumption. The cultivation of seaweed isn’t new for Shinnecocks — it’s thousands of years old, actually — but as the world gets more polluted, kelp’s chemical absorption properties have come to the fore in international green efforts as a part of the fight against climate change.

“Shinnecock Kelp Farmers have been in the making for a very long time,” said Darlene Troge in an interview for the forthcoming documentary Kelp Movement, which features the Shinnecock Kelp Farmers. “We have come together to share our family stories and traditions, to really work together to save mother Earth, and to tell the story of seaweed.”

Spurred during the pandemic and noted increases in carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in the bay from overdevelopment in the Hamptons, they began to cultivate and later harvest sugar kelp, which naturally absorbs excess chemicals that have been poisoning our bay for decades.

After COVID became a reality in 2020, many wealthy city denizens decided to leave the spookily empty Manhattan for less urban surroundings, moving to the Hamptons to become full-time residents. The increase in wastewater runoff and groundwater toxicity, largely from expanded septic systems and use of chemical fertilizers on the lawns of expansive properties, has allowed this untreated wastewater to enter the bay.

It continues to kill marine life, powers algae bloom deadly to water creatures, and threatens to destroy not only the Shinnecock people’s reliance on what used to be a reliable source of food, but also the safety of marine fisheries farther afield.

The collective of Shinnecock women, who are tribal citizens but are not operating their nonprofit farm under the tribe’s aegis, saw the urgent need to leverage the 12,000-plus-year-old traditional relationship our people have with the sea and with seaweed for greater good. Kelp is good business — after it helps clean the water, it can be harvested for food products and also as a natural fertilizer.

And unlike many in the kelp business, the Shinnecock Kelp Farmers are doing this work more to restore the bay than for profit. Because they are not a Shinnecock tribal entity, they are ineligible for federal grants, and thus they must rely upon donations and nonprofit grants to fund their work instead.

They have been supported with a bayfront location and far more by the Sisters of St. Joseph in Brentwood, a congregation that has long adopted an environmentally conscious stance. The sisters also know that they are on “occupied Indigenous land” and have included a land acknowledgement on their website and elsewhere.

When the Shinnecock Kelp Farmers approached the sisters to collaborate after a kindred 2019 repatriation and burial effort of Shinnecock ancestral remains in the sisters’ Brentwood cemetery, the congregation enthusiastically agreed to support the kelp project. The kelp farmers are also getting technical assistance from Greenwave, an ocean farming incubator.

The kelp farmers believe in educating others as part of a holistic growth practice, and frequently participate in local and national events supporting environmental advocacy and educating the public on the practice of growing kelp. Early this year, director Tela Troge joined partner Greenwave in a live online conversation about starting one’s own kelp farm.

And the Kelp Farmer’s efforts are already being paid back by large organizations recognizing the import of the work they are doing, such as The Nature Conservancy, awarded them $75,000 to capture carbon and reduce nitrogen pollution in Shinnecock Bay.

Documents from the 1600s show that colonial settlers, who stole most everything else from our people, still reserved the right for Shinnecock people to harvest seaweed. They must not have known the intrinsic value; more recently, as a matter of historical case work, the “seaweed cases” were cited by tribal attorneys in our decades-long application for federal tribal recognition, which took until 2010 to achieve.

But the story of seaweed amongst Shinnecock and coastal Indigenous people everywhere goes back even farther than early documents suggest — carried forth and brought back into environmental healing practice by this group of six strong women.

They bring the nurturing practices of helping children grow to their young kelp plants in the hatchery — after reading studies suggesting that talking to plants actually does help them grow and that the farmers’ microscopic plants benefit from singing at higher frequency tones and high vibration “kind words,” according to kelp farmer Danielle Hopson Begun.

“In our hatchery, we sing our traditional (Shinnecock) water honoring songs and lullabies, read Joy Harjo poetry and express gratitude and beauty,” she wrote in an Instagram post.

“Doing this good work that’s healing the bay while benefiting future generations is just what we know as Shinnecock people,” says Darlene Troge. “Because of the way we were raised, on the reservation, it’s never been owned by anyone, we were taught that the air, the water and the land belongs to everyone. So we are uniquely positioned to realize what mother Earth is saying to us. Saving mother Earth is not just the job of Indigenous people, but of all people.”

Donations to support the mission and operation of Shinnecock Kelp Farmers are welcome at shinnecockkelpfarmers.com

Alli Joseph is a journalist, producer (Conscience Point), advisor on the forthcoming documentary Kelp Movement and citizen of the Shinnecock Nation.

“Shinnecock Voices” is a monthly column in which citizens of the Shinnecock Nation share stories and opinions and discuss the projects and campaigns they’re working on, to allow readers an inside view into their incredible community.