The Changing Role of Hamptons Beach Stickers

As the ocean beaches along the 50-mile stretch between Westhampton and Montauk become available for the summer visitors, it reminds me of that brutal freezing cold day last January when, at 6 a.m., grim and determined local people lined up in the dark at the East Hampton Fire Department so that at 9 a.m., when the doors flew open, they would be among the fortunate few permitted to pay $500 to buy one of the few precious non-resident beach stickers allowing them to park in the village beach lots in the summertime.

Without that, it would be a long walk from where you could legally park. Probably too long for lugging a beach umbrella and folding chairs.

People who got stickers, braving the long wait at the doors that morning, came away in triumph holding up their passes. Just a half hour after the doors opened, the rest would be turned away.

How has it come to this?

Back in 1956, when I first set foot in the Hamptons as a teenager, there were the same number of beaches as today, but there weren’t beach sticker requirements.

You could park at any beach, drive on any beach, run your dog free, enjoy a party, have a bonfire, sleep the night there, or even, at some beaches, go topless.

Four years after we came, I started Dan’s Papers.From then on, I had my finger on the pulse of the community, and from that moment on, it was all downhill as far as beach stickers were concerned.

In the summer of 1975, the Town of East Hampton hired a man known for his wisdom and fairness, Frank Borth, to recommend what to do about the parking situations at our beaches. He was to think about it and, in the spring, 10 months later, make a report.

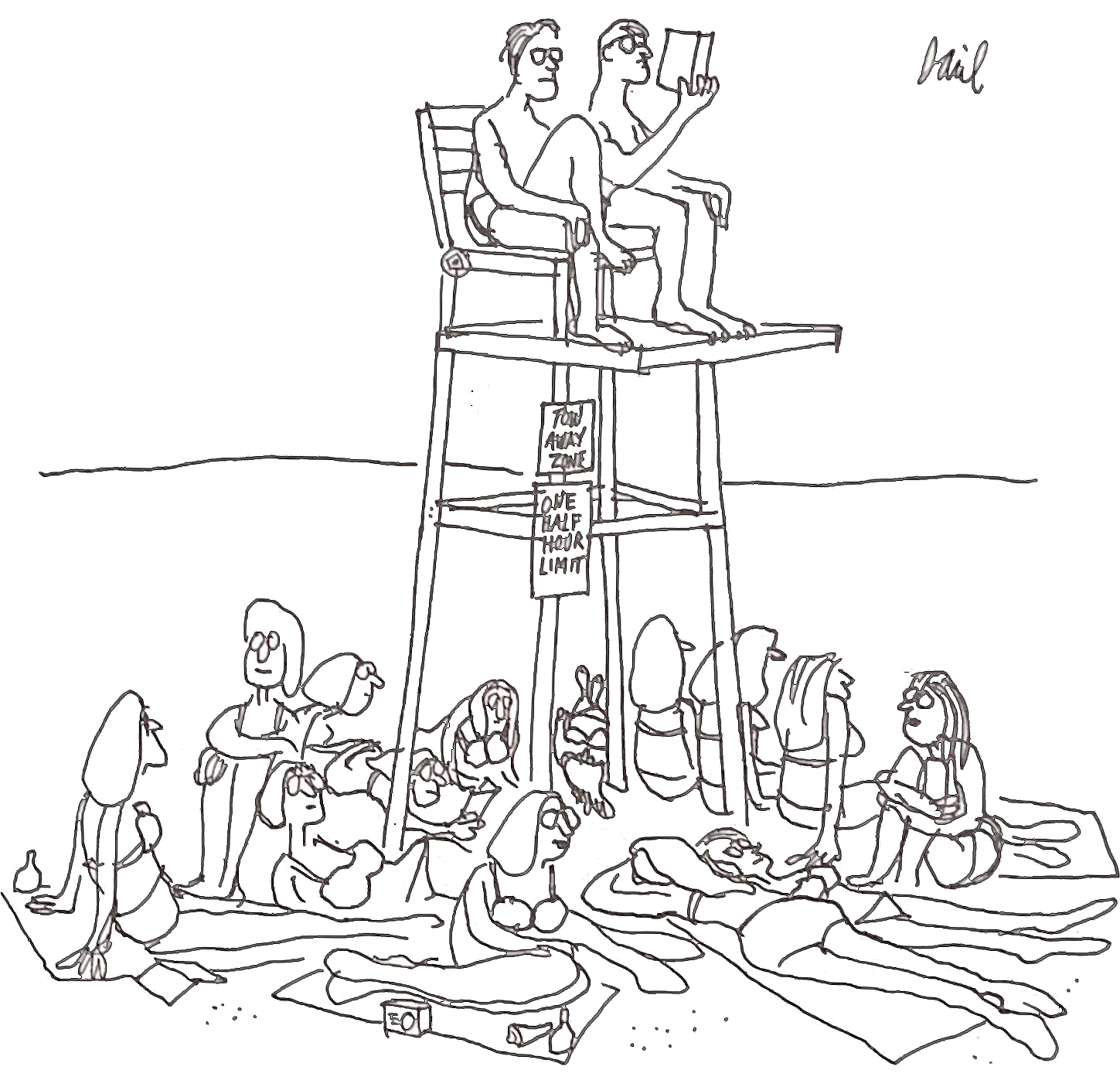

Borth and his wife lived in a small house in Hither Hills, Montauk. He was a famous syndicated cartoonist, his work appearing in the comic sections of probably half the newspapers in America at that time. Working on an easel at home, he’d make his drawings while enjoying a view of both the ocean and his 2-acre pasture where, for his daughter, he kept a horse. When done, he’d mail his drawing off by special delivery.

I got to know him. Some of my advertisers hired him to draw ads for the paper and so sometimes, I’d stop by and pick up the art. He was thoughtful, shy and kind. Here, because he was thought to be a wise man, he had this assignment.

The following summer, the Town of East Hampton put into effect what he proposed. It was beach stickers, one kind for the locals, another for the summer people. Cost a few bucks. Stick it on your car. This was pretty much what other resorts such as Cape Cod or the Jersey Shore did. As it was nothing unique, it was, in my view, a disappointment.

If East Hampton Town was first, within a few years, all the other towns and villages passed such laws too. And, I think, coordinating with one another, each chose a different color so, at a glance, you knew which was which.

Initially, we were told our local beach sticker would be good in all the other towns. But that only lasted a year.

I recall during this time writing a sarcastic story stating that if you wanted to go to every beach as you had before, you’d have to get a checkerboard of colorful stickers that would make it impossible to see where you were going.

And then, beginning about 1985, at some beaches, stickers would be available only to the immediate residents. None were available to anyone else. When this was announced, the painters, sculptors and authors in the artists colony in Springs suddenly could not go to Georgica Beach, their regular gathering spot.

As a result, Willem de Kooning, the most famous living painter in our community, said he would no longer participate in or attend events at Guild Hall arts center in East Hampton Village because the village had evicted him and his friends. Indeed, he stuck to that vow until he died in 1997.

In the 1990s, there was a spate of beach sticker robberies. People would come back to their cars at the end of the day to find the sticker scraped off their car windows. Since there were no license plate numbers on the stickers, it was impossible to trace them. The following year, the villages and towns added the license plate numbers, which ended that practice.

However, it now seemed that, with further restrictions in the townships, there would be only one ocean beach in your unincorporated community you could go to with a summer-long pass.

Also at that time, beach sticker forgery came into existence. Counterfeit stickers, both crude and almost indistinguishable from the real thing, were now on cars. When arrested, the names of these forgers appeared in the town police blotters.

By 2000, dogs could no longer run free at the beaches, except in the off-season, and even then, only if they were “under your control,” whatever that meant. Signs at beach entrances said dogs were welcome, but arrows pointed to a distance 200 yards away from the bathers to which you had to walk before your dog could be let off his leash.

And several years ago, vehicles were banned from the mile long ocean beach known as Truck Beach in Amagansett. And this year, it appears the vehicle ban might also go into effect at Picnic Beach in Southampton.

And so, in recent times, my family and I — the home we own is in Springs — are able only to get summer-long stickers to the single beach in Amagansett reserved for us: Indian Wells. We also, for a while, could go to Sagg Main, because I owned the building in Southampton Town that housed our offices. And that qualified us for a sticker.

However, we outgrew that property. And so, after selling it, we were no longer eligible for a Southampton beach sticker. This saddened me greatly.

What next? Dunno. Maybe this February there will be wrestling and other kinds of pitched battles to gain beach stickers. If so, you’ll read about it in Dan’s Papers.