Ospreys in Love vs. PSEG on the North Fork, Digging to China

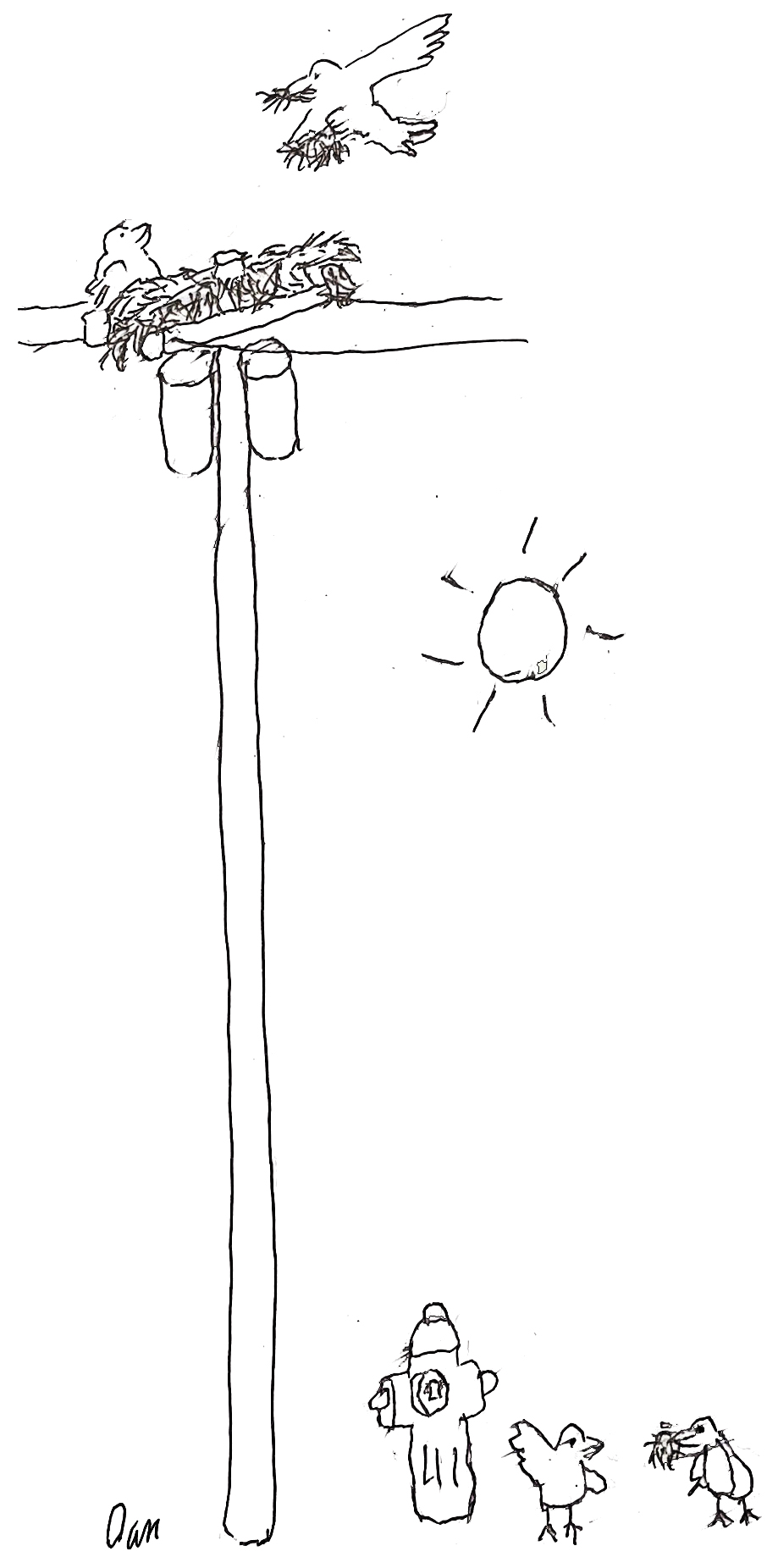

This is the season when ospreys, magnificent raptors with 5-foot wingspans, having paired off and nested high up atop telephone poles, hatch their young and begin feeding them. You’ll often see the chicks up there, quivering in anticipation, their beaks open, awaiting food. Mom sits nearby, watching and guarding the chicks, while Dad, flying over ponds and harbors looking for fish to swoop down upon, eventually dives down into the water to emerge with dinner for his hungry family.

The osprey is one of the wonders of the East End. Nests on these high-up platforms are everywhere, particularly along farm lanes. The companies that put these platforms up, either PSEG Long Island or Verizon, will see these birds courting in April and early May, then making nests on equipment attached near the top of the poles. The utility companies intervene, build wooden platforms further up, and the osprey, seeing that these are better, oblige by nesting higher.

Here, however, hangs a tale.

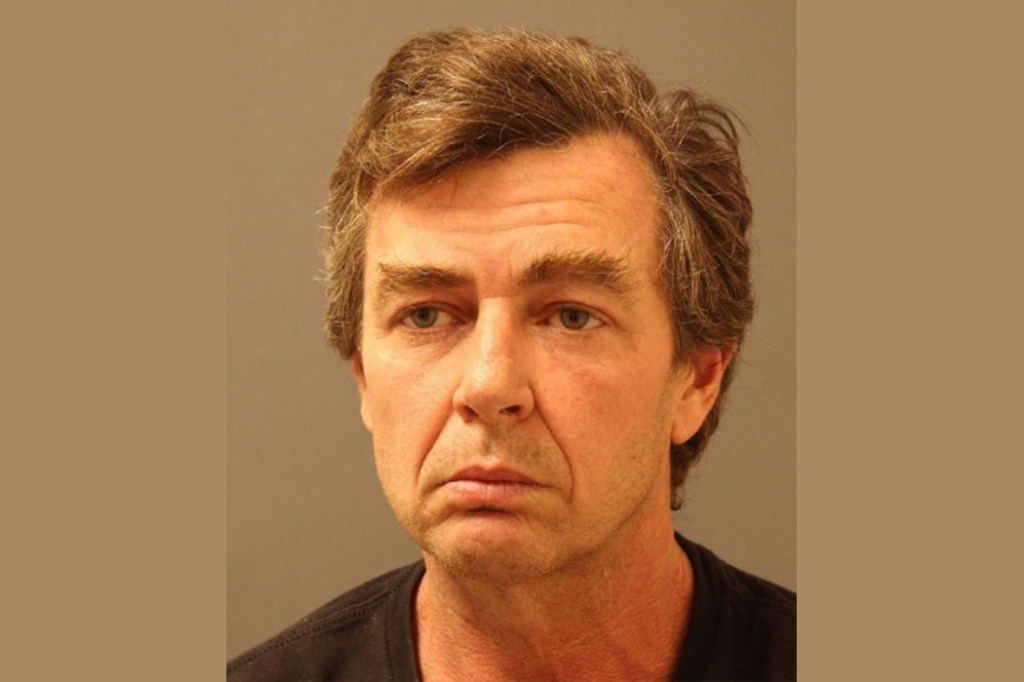

Deb Stroup is the vineyard manager at Bedell Cellars on the North Fork. She is out there in the fields with the rest of the vineyard workers, rain or shine, tending the plants and, when the time comes, harvesting their grapes.

The winery, vineyards and tasting rooms occupy some 80 acres of flat farmland in the unincorporated hamlet of Peconic just west of Southold. From the vineyard, you can see for miles. And while Stroup has been out there, she’s often seen the ospreys come and go from their high-up nests atop the poles, particularly along the Main Road heading east toward Southold.

A few months ago, however, she and the other field hands watched what seemed to be some kind of pitched battle between an osprey couple and PSEG Long Island, the local power company. Along a stretch of Main Road between Wells Road and Peconic Lane, the two ospreys had begun to build a nest on the equipment near the top of a particular pole.

The male would fly off and bring in twigs, grass, seaweed and branches. The female would stamp on these things to shape them into a nest. Some nests, either on equipment or platforms, get to be 6 feet across. But in this case, a PSEG truck appeared, and the workmen, wearing helmets, climbed up the pole and using sticks, shooed the ospreys off.

Eventually, of course, they succeeded and the birds, agitated and upset, fluttered around nearby, then after a while, flew off. Seeing this from afar, Stroup wondered what was happening. Soon, the workmen put a cap over the equipment. It could no longer be used as an osprey nest.

The next day, Stroup watched as the two ospreys were back now working to put up a nest on a second equipment pole further down the road. And again, PSEG intervened. The next day the fight continued on a third pole. What the heck was going on?

At the end of that third day, Stroup wrote a letter to PSEG. Further down Main Street but across the street, she wrote, there were poles with no equipment on them. Couldn’t PSEG put a platform atop one of the poles across the street if there were something wrong with this side of the street?

Shortly, she got a response from PSEG Communications Senior Generalist Jeremy Walsh. PSEG was committed to protecting the osprey, he wrote, and works with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the Group for the East End, both important environmental groups. But also, PSEG considers electric system reliability. So there are limits.

These are juvenile ospreys, he continued. They are not mature enough to lay eggs. So at the end of the day, there will be no new chicks up there. However, during the osprey adolescence period, sometimes, adolescents inappropriately pair off and try to build what PSEG calls “practice nests” on the poles. This is not proper. They should nest in the crooks of trees. That’s what other adolescent ospreys do.

I do not know if Stroup and her crew thought consciously of the Shakespeare play Romeo and Juliet. In that, Romeo, age 16, falls in love with Juliet, who is 13. Mad for each other, they wish to pair off together, perhaps build a life together. But their two families, the PSEGs and the Verizons, no, the Montagues and the Capulets, declare it inappropriate. The play ends tragically with Romeo and Juliet, unable to go on if they cannot be together, committing suicide.

In any case, this letter was not satisfactory to Stroup. The lovers wanted a nest on a pole.

Stroup and her crew took matters into their own hands.

She met with the owner of Bedell, Ninah Lynne, and told her what she had in mind. Lynne approved. Bedell would build a platform on a pole on private property. PSEG could not stop them.

Stroup contacted the North Fork Audubon Society and got architectural plans. They bought the wood, which cost about $500. They got a carpenter Edwin Cruz, who agreed to donate his time. The osprey platform went up. It is there on the Bedell property today.

And did the ospreys come?

“The two ospreys flew over and checked it out. They didn’t take to it at first, and instead flew off and circled around over other PSEG poles on the Main Road,” she told me. “But then, as it happened, a smoldering fire broke out in the equipment atop one of the PSEG poles. The power company rushed over and put it out. And with that, the two young ospreys decided that maybe the pole up on our property was pretty good after all. So they built the nest and moved in.”

And so, the tale ends. The two are living happily ever after on a platform and pole in back of a PSEG pole on the edge of Bedell property. Go to the vineyard and see the young lovers for yourself. Tell them I sent you.

DIGGING DOWN

On June 1, Chinese scientists began drilling a hole in the ground at Xinjiang that will be deeper than any ever dug before in China. It will advance human understanding, according to China’s President Xi. What will they find? I believe they will find themselves in the backyard of the house I grew up in when I was 7.