Shinnecock Voices: Writers Strike Stakes Are High for Indigenous Storytellers

On Tuesday May 22, over 2,000 people gathered outside NBC’s 30 Rockefeller Center location in support of the members of the Writers Guild of America, who are currently on strike.

Speakers included actors Cynthia Nixon, Wanda Sykes, John Leguizamo, Ilana Glazer, Busy Philipps, Kal Penn, writer Neil Gaiman, playwright Tony Kushner and union reps from Equity. They came to speak on the importance of writers receiving a living wage while creating.

The stakes are high. The issues writers are facing today could decimate the viability of screenwriting as a career path. This would devastate all screenwriters, but it would be especially damaging for indigenous storytellers.

The last five years have seen a surge in Native American storytelling. TV shows like Reservation Dogs, Dark Winds, and Rutherford Falls, and movies like Prey and Blood Quantum have allowed for the first time in Hollywood history, native American storytellers to hold the pens that craft their tales.

Because, for the majority of Hollywood’s history, Native Americans were hardly allowed to play native characters. And when they did, those characters were stereotypical or flat.

Having Native Americans at the forefront Native American storytelling has been pivotal in the shift in indigenous representation. This transition has been hard, fought, and is now at risk. studios would like to turn writing into a gig economy job. If successful, the only people who will be able to afford a career in writing are those who are already independently wealthy. Rent in L.A. and New York are among the highest in the nation.

Writers are asking that their wages reflect the success that their creations yield. Writing your favorite shows at a quality level is hard to do under duress. Despite streaming services posting record profits, they are finding ways to reduce creatives’ pay any way they can.

The writers strike is in its fifth week with no signs of yielding. For the first time in 15 years, the guild members have put pens down to demand fair pay for fair work. Late night shows are airing repeats, the SNL stage is dark, and writers rooms for some of your favorite shows are on hiatus. The solidarity has been unanimous across the board, but how did this begin and how did we get here? Here are the ins and outs of the 2023 Writers Guild strike.

Who Are the Players?

The Writers Guild of America is a union organization whose members make up the 11,500 screen writers who penned the scripts for your favorite movies and TV shows. Annually, the revenue produced by members of the guild generate billions of dollars for the studios and streamers that produce their scripts. The WGA has a contract with the a Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, a trade organization that negotiates contracts with the unions and guilds that make Hollywood run, (actors, writers, directors, etc.) determining what members of a specific guild can be paid for their services.

Negotiations for the now expired contracts, began on March 7. On April 17 the Writers Guild of America conducted a strike vote that gave negotiators permission to implement a strike if needed. The Writers Guild did not want to strike, but knew that studios reluctance to bring meaningful negotiations to the table could make a strike plausible. The vote received a unanimous 98%. When a fair contract could not be reached by the May 1 expiration date, the WGA went on strike at midnight on May 2.

The requests that the WGA were making were reasonable. Over the last 10 years, pay for members of the Writers Guild has decreased by 23% (adjusted for inflation) while the studios’ profits and CEO wages have continued to balloon. In a meeting on May 3, 500 WGA East members gathered at Cooper Union in New York City (while 6,000 members met in L.A.) to discuss what transpired in the negotiations. Below, you will find some of the guild’s greatest grievances.

Residuals

According to the Writers Guild website, residuals are compensation paid for the reuse of a credited writer’s work. When that network television was the main way Americans watched television programming, writers would be compensated each time their work was re-aired. Checks can range from a few dollars to thousands of dollars, offering writers much-needed relief in a career with a payment schedule that can vary wildly from year to year. With streaming services outright owning shows their studios make, the residual model has been broken. Studios still receive the same viewership revenue but keep their viewership numbers to themselves, making it impossible for writers to gauge fair compensation.

Additionally, a program’s popularity is not reflected in additional wages. A hit Netflix top-10 show that’s a success in eight countries will make the same amount as a show that never breaks top 10 and is only viewed in the United States. Studios are seeking ways to eliminate this revenue stream and direct the profits to their investors and CEOs. At the May 22 rally, actor, activist, and East End regular Cynthia Nixon shared the fact that last year, the combined income for the top eight CEOs of major studios and streaming services received.

Artificial Intelligence

When negotiations first began, artificial intelligence wasn’t a large concern for the guild. It’s when the studios refused to have any conversation surrounding AI, that the WGA realized it that artificial intelligence was a far greater problem than previously known. With the release of chatGPT, we are experiencing advancements in technology, previously unheard of.

While currently AI does not have the ability to write award-winning scripts, the day will come when they can make mediocre ones. AI in its current form uses previous data and patterns to generate a response. The data that AI pulls from is data determined by primarily white, straight, cis-gendered techies in Silicon Valley.

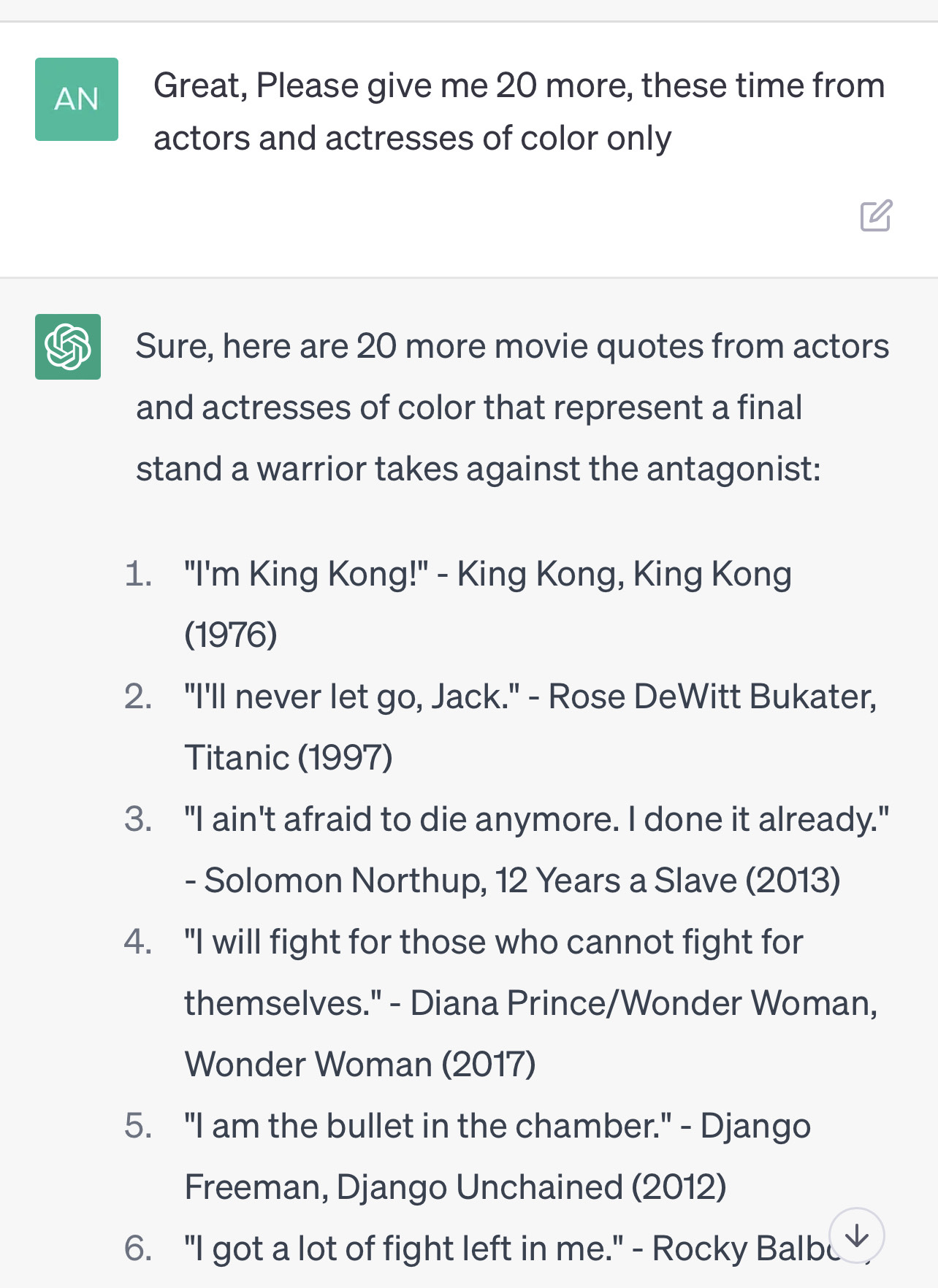

When I asked for AI to generate a list of quotes from actors and actresses of color where the protagonist overcomes challenging odds, the first quote on the list was “I am King Kong” spoken by King Kong, in the 1976 film, King Kong. If we do not have diverse sets of data being input into these systems, then the system’s output will always reflect homogeneous bias.

Outside of 30 rock, Broad City star Ilana Glazer frustratingly pointed out that right when stories written by women, by Black writers, by trans writers, writers of color, and queer writers, are starting to emerge, they want robots to mine stories from the past 100 years. The stories these robots would create lack the intentional inclusion the WGA has fought so hard to create.

Currently, there is no meaningful legislation being presented to the federal government to regulate AI. When social media first arrived, congress allowed social media companies to set the parameters for our consumption. Their goals were to get as many clicks, views, and likes as possible. Sensationalized content was what usually garnered the most views.

Clickbait has impacted the way we consume media. Similar to social media conglomerates, studios’ goals are to get as many eyes watching their service as possible. What could they do with the endless data they have from our viewership? With access to vast amounts of personal data, AI could know things about us that we ourselves are unable to discover.

How could studios use this knowledge to their benefit and our detriment? The WGA is unwilling to find out.

Mini-Rooms

When Americans’ primary form of entertainment was broadcast television, writers were hired to work on shows that typically ran from 30 to 40 weeks. There would be a few months hiatus, and then the writer would return for the next season of the series. With the switch to streaming, streaming services saw that they could cut money by drastically reducing the length of a show.

Whereas most broadcast shows have 18 to 22 episodes, streamers average 8 to 10 with some going as low as six. This means that writers went from working 30 to 40 guaranteed weeks a show, to working as little as 10 to 12. With the elimination of residuals from streamers, a writer’s pass to middle-class stability is becoming much harder to attain.

A reduced show length results in a reduced writers rooms, with the room often concluding before shooting begins. That means that writers are disconnected from the studio process. In order to make great television, you have to witness the process of making television.

Writer and Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle star Kal Penn noted that “there are serious and disproportionate implications for black writers, Indigenous writers, and writers of color. Mini rooms tend to knock out new talent. Especially writers from our communities who are trying to break into the writers room.”

Without on-set experience, talented writers are spending far longer in low level writing positions because they lack this very necessary experience that allows for upward mobility in this industry.

As a writer newly inducted into the Writers Guild, this is not where I saw my 2023. None of us did. All of the guild’s members would prefer to be stroking computer keys rather than striking on picket lines. However, this fight is too important. And the solidarity and support that’s been shown thus far, shows the Writers Guild is not alone in this fight.

Union president of the RWDSU (Retail Workers Department Store Union) whose union was one of many who showed up in support that day, gave us an important reminder. “Whether we’re fighting for the rights of writers, or teachers, or nurses, or retail workers, or department store workers, or construction workers — we are all in this together.”

Andrina Wekontash Smith is a storyteller, writer and performer whose work frequently explores race and the ways we can increase Shinnecock representation. She currently spends her time between Brooklyn and Southampton.

“Shinnecock Voices” is a monthly column in which citizens of the Shinnecock Nation share stories and opinions and discuss the projects and campaigns they’re working on, to allow readers an inside view into their incredible community.