Shootout at the Ranch: Trouble at Montauk's Third House

When William Delmadge was 18, his father arranged for him to become a New York State Trooper. His dad thought he was a no-good son of a bitch. Maybe being a trooper would straighten him out. It didn’t.

One of the first jobs Delmadge got involved with was getting the monthly payment from the Dickinson family out at Third House in Montauk. This was in April 1925, 98 years ago.

Delmadge was taken out there from the police barracks in Bay Shore by Ed Granger, an older officer. They traveled through the woods to Third House around 4 in the afternoon, knocked on the front door, and when Frank Dickeinson opened it and looked them up and down in their trooper’s uniforms, he said just a minute, left and returned with five $100 bills.

“What was this all about?” Delmadge asked as they walked back to the car.

“There’s hundreds and hundreds of boxes of illegal hooch stored by the rumrunners here. Us troopers ‘guard’ it. It means we show up first of the month and they pay the fee.”

“And the chiefs at the barracks know about this?”

“Some of them,” Granger said.

Delmadge was quiet most of the rest of the way home. He was thinking.

At 2 o’clock in the morning a few days later, five men, armed with rifles and pistols, banged on the front door of Third House. Ed Granger was not one of them. But 19-year-old Delmadge was. He’d put this together. The headlights of two vehicles shone on the front door. With him was Jeremiah O’Keefe, an ex-trooper, and William Shaber, another ne’er-do-well friend of Delmadge. Frank and Thomas Smith of Patchogue were in the other vehicle, a large moving van they owned.

The door opened and a bleary-eyed Dickinson stared at them. He spoke to Dalmadge. “I remember you,” he said. “I already paid the fee.”

Upstairs, now wide awake in their beds were Dickinson’s wife Loretta, their three children, Shank, Phineus and Eleanor, age 4, 7 and 11, and, in another bedroom, Frank Dickinson’s father, also named Phineus, age 70.

The five men cocked their guns. “All the liquor boxes go in the van,” Delmadge said.

And with that, the men entered and Frank, saying “no problem,” led them to the west wing and the barn. Loading all these boxes would take hours.

None of the men, however, had seen Phineus Sr., in his nightclothes, at the top of the stairs, taking in all that was happening.

At this particular time, nearly all of Montauk was woods. A few miles from Third House, on the narrow beach at Fort Pond Bay, there was a small village occupied by about 100 Canadian fishermen from Nova Scotia and their families who’d built boat docks and shacks out of scrap wood on property they did not own. The village had a post office, school, store, bar, restaurant and general store.

By day, the Canadians went out fishing. By night they would take their fishing boats to the freighters anchored just beyond the 12-mile limit, take on the crates of illegal liquor they had and motor them to shore — and from there off to Third House a few miles away where they could be stored until the gangsters, the bootleggers, came out from New York City to fetch them. The Canadians were paid well.

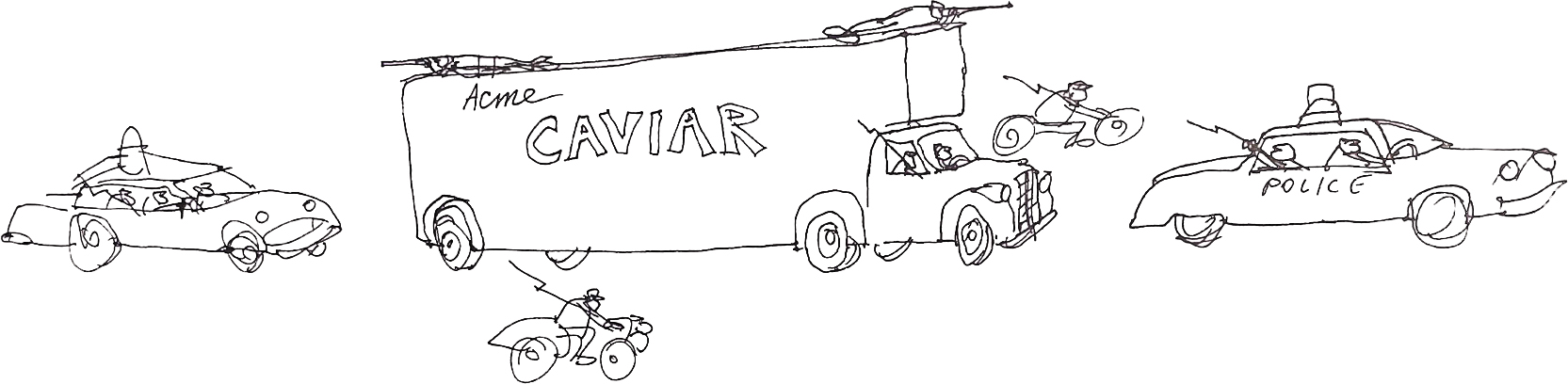

There in that moonlight, Phineus quietly sneaked out the back stairs, climbed on a horse and fast as he could rode off to the fishing village to round up the Canadians. An hour later, two truckloads of Canadians carrying shotguns, pistols and rifles, drove up to the front door of Third House, intercepted the robbers, and engaged them in a brief gunfight. Both Delmadge and Frank Smith, sitting in the van, were hit. They screamed. It was over.

Both were pulled from the van and thrown to the ground by the fishermen, who then stripped Delmadge of his badge, shield, belt, hat, lanyard, cartridge belt, pistol and boots. They then had the remaining bandits take the wounded troopers to a doctor.

There’d been a drunken brawl, they told the doctor, who patched the two men up. He said Delmadge was running a low fever and should be kept in bed overnight. After the men left, Dr. Edwards called the police.

The police found Delmadge in bed at the home of his girlfriend, Helen Smith. Delmadge repeated his story. Smith, however, said Delmadge stole her car. She didn’t want anything more to do with him.

Also that morning, the police came to Third House, handcuffed Frank Dickinson and took him off to jail in East Hampton on charges of possessing alcohol. However, enough Canadians went to the court arraignment later that day, bailed Frank out and got the charges reduced to a misdemeanor.

Eventually, Delmadge and his four compatriots were put on trial and sent to jail. But it all wasn’t over. This whole thing, covered extensively in the New York daily papers, was a huge embarrassment to the U.S. Coast Guard, which announced that there would be a massive raid on the freighters. There would be an armada of 42 picket boats, 8 cutters and 12 seaplanes to attack the freighters the following week. Of course, learning of this, all the freighters motored out beyond the 12-mile limit, waited until this “Dry Navy” raid, as it was called, finished its operations, and then came back.

A day after the gunfight, Federal Revenue Officers came to Third House with crowbars and sledgehammers to pry open all the boxes and smash all the bottles, sending alcohol, wood and shattered glass throughout the home.

“They also destroyed, furniture, children’s toys, beds, lamps, hunting rifles and everything else,” Shank Dickinson, who was there as a child, later told me. “It took five people three days to clean up the mess.”