Summer on My 'Yacht' – Living the Good Life on a Derelict Houseboat

Back in the early days of Dan’s Papers, I used to sell all the ads myself. In the spring, I’d stop by the merchants one by one and show them my plans for the summer and they would say yes or no. One particular year, I was having serious personal problems and although I’d start up talking about the paper, I’d end up talking about my problems.

“She doesn’t want me anymore,” I’d say, tearing up. “I have to move out.”

Most merchants felt sorry for me, but had no way of helping. As we were now on to another topic, the sales slumped. It wasn’t going to be a good year.

And then I told my tale to Florence Palmer, an older woman who owned a restaurant and marina on Three Mile Harbor. (Today the restaurant is known as Sunset Harbor.)

We were looking out at the rows of boats rocking in the slips.

“I have an old boat you could live on for the summer if you want,” she said.

“You do?”

“I’d be happy to have you stay here.”

She indicated what was, at that moment, the largest boat tied up in her marina.

“I could pay,” I said.

“Nope. You’re having a hard time. This is what friends are for. Nobody’s using this boat.”

As we walked down the dock to have a closer look, Palmer told me about it.

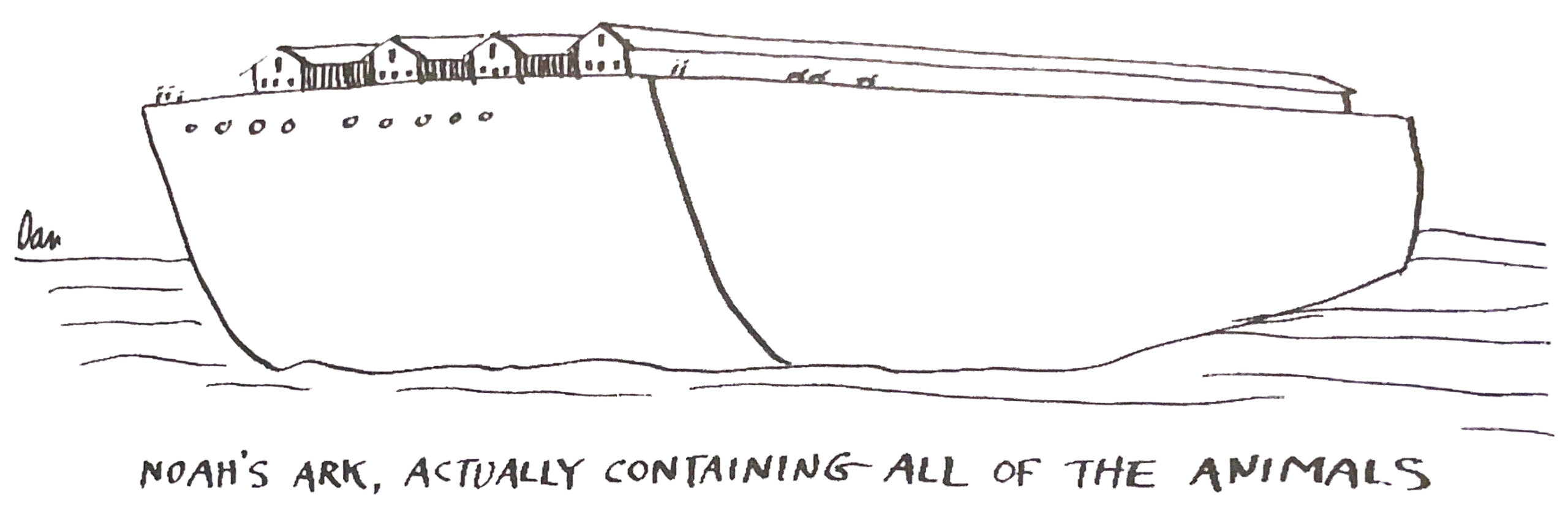

“A wealthy man fell in love with this broken-down boat in Connecticut and had it towed here,” she said. “He said he intended to restore it. But then, apparently, his wife vetoed the idea. So he never came. He’s abandoned it. It floats. But it doesn’t go.”

I had one of the most amazing summers ever.

Let me describe what was in this slip. The ship was 54 feet long and, according to an old stained manual in the wheelhouse, built by ACF (American Car and Foundry Company) in 1932 as a touring yacht to take wealthy people from one yacht club to another during the summer social season. Made entirely of mahogany, it had circular holes in the sides for portholes but no portholes, twin four-cylinder inboard engines below seized up and no longer able to start, bunkbeds in the bow for a necessary two-man crew, a kitchen with no running water, a dining room with stained glass and mahogany cabinets for the crockery but no crockery, a place for a dining table but no table and a wheelhouse with all sorts of broken gauges and a ship’s wheel that spun freely.

Through a small door, stairs led down from the wheelhouse to a corridor with two bedrooms on one side, another bedroom and a bathroom (that worked) on the opposite side and under a deck at the stern, which had a metal frame for an overhead awning but no awning, a master bedroom featuring a bed with a beautiful wooden headboard carved with colorful woodland animals to help you sleep. Nowhere, however, was there electricity. On the other hand, an extension cord attached to an outlet at the dock spooled out aboard and down into the engine room, where a motor hummed on and off as it pumped water back out of the boat through a hole just above the waterline so this ship could continue to float.

It was love at first sight.

But it needed work. At Village Hardware on Newtown Lane in East Hampton, I bought a hammer, nails, big plastic letters that said Phoenix (I’d named it), paper plates, cups, plastic spoons, knives and forks, toilet paper, napkins, paper towels, lanterns, large white painters tarps to lash with clothesline to the awning frame above the rear deck for shade, eight folding captain’s chairs for the deck, cleaning supplies, flashlights, more clothesline to zigzag up and down on the railings all around to keep people from falling off, soft drinks, chips, a bag of ice and a Styrofoam cooler.

What a summer that was. Among other things, I had covered-dish banjo jam sessions for family, friends and musicians every Saturday night. People on neighboring ships in the slips joined in the singing, which, by agreement, started just before the sun set over the far shore at 8 and ended at 10.

About a week after I moved in, a 46-foot Chris-Craft pulled in to the slip next to mine. All shiny and new, its captain had motored it up from Florida. We talked. He said the owner, whom he worked for, planned to come out for weekends. But the weekends went by and he didn’t. However, on a Friday in late August, I saw the captain striding happily down the boardwalk with bags of groceries.

“He’s coming,” he smiled at me. “I’ve got sirloin, Champagne, caviar, the works.”

But no, he didn’t. He canceled. So, Saturday night the jam had the best dinner ever. And after that, the owner still never came.

Having made other arrangements, I left the boat around September 15. A chill breeze had come through. In October, a small, quirky man, saying he wanted to talk to me about the boat, was ushered upstairs to my office.

“I’ll get right to the point,” he said. He sat. “I intend to buy the boat you were on this summer and restore it. I’m going to have it towed to New Jersey. Did you know this yacht was featured as the centerfold of Motor Boating magazine in July of 1932?”

“No I didn’t,” I said.

“This is a very valuable boat. But I have a question. Where is the dory?”

“What?”

“The ship had a dory. A small tender for motoring people to shore and back.”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“It’s made of mahogany. Quite valuable. You sure you don’t have it?”

“I don’t have it and I don’t know who has it. I’ve never seen any dory.”

He leaned forward and looked at me suspiciously.

“Are you sure?”

“My guess is, a local clammer took it. Probably painted it white. I bet it’s out there somewhere.”

He stood. He took a business card out of his pocket and handed it to me.

“If you ever come across the dory, call me immediately,” he said.

And then he left.

The next spring, Mrs. Palmer told me the boat was gone. She didn’t know where. The bill was paid. Partially.

“I think it was that little man,” she said.

And that was that.