The Controversial Life of Larry Rivers Explored in New Doc

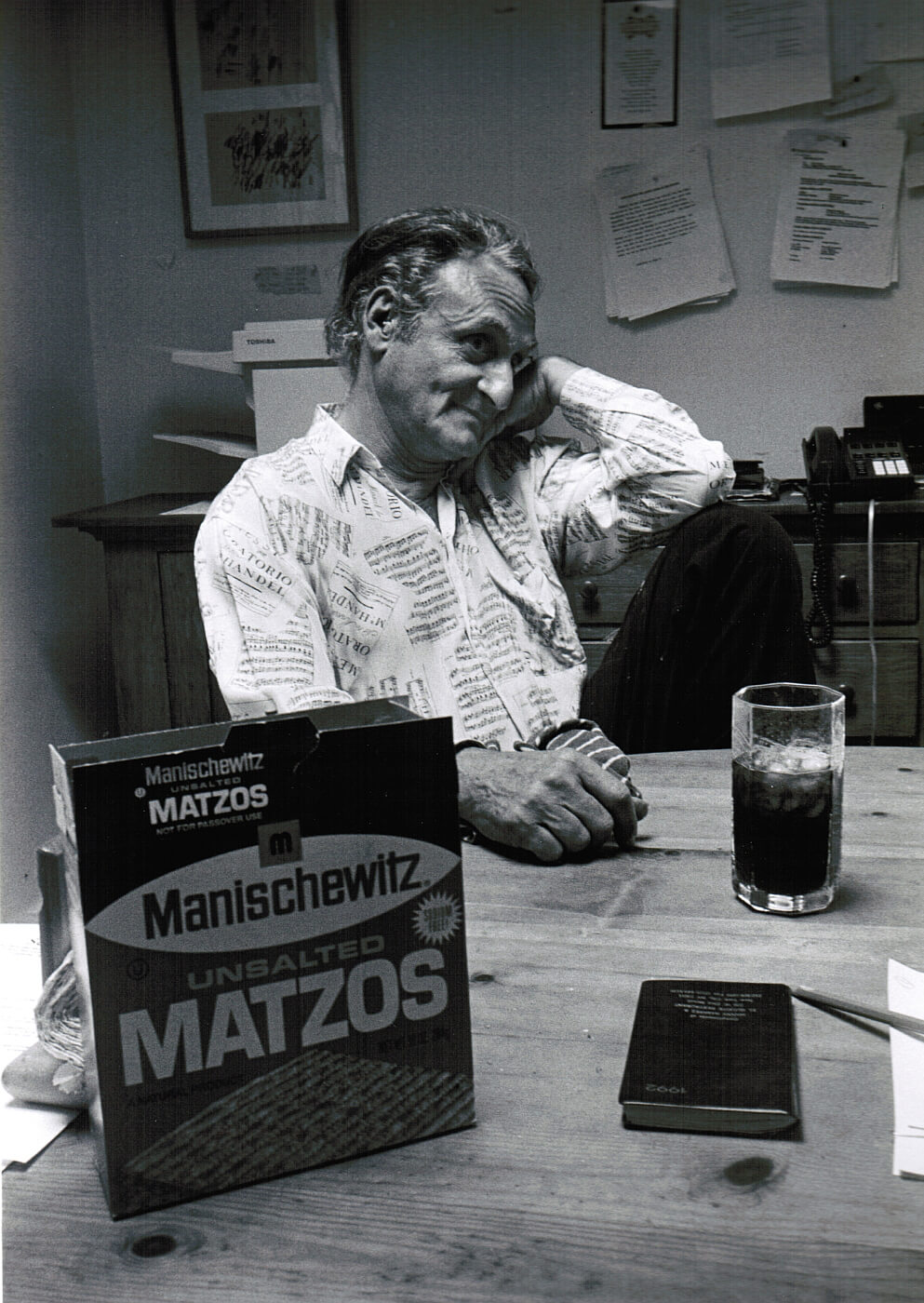

The Hamptons was, and still is, famously home to some of the greatest and most celebrated artists of all time, but that vaunted list — including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Motherwell and Andy Warhol, among so many others — often leaves out the exceptional grandfather of Pop Art, Southampton’s own Larry Rivers.

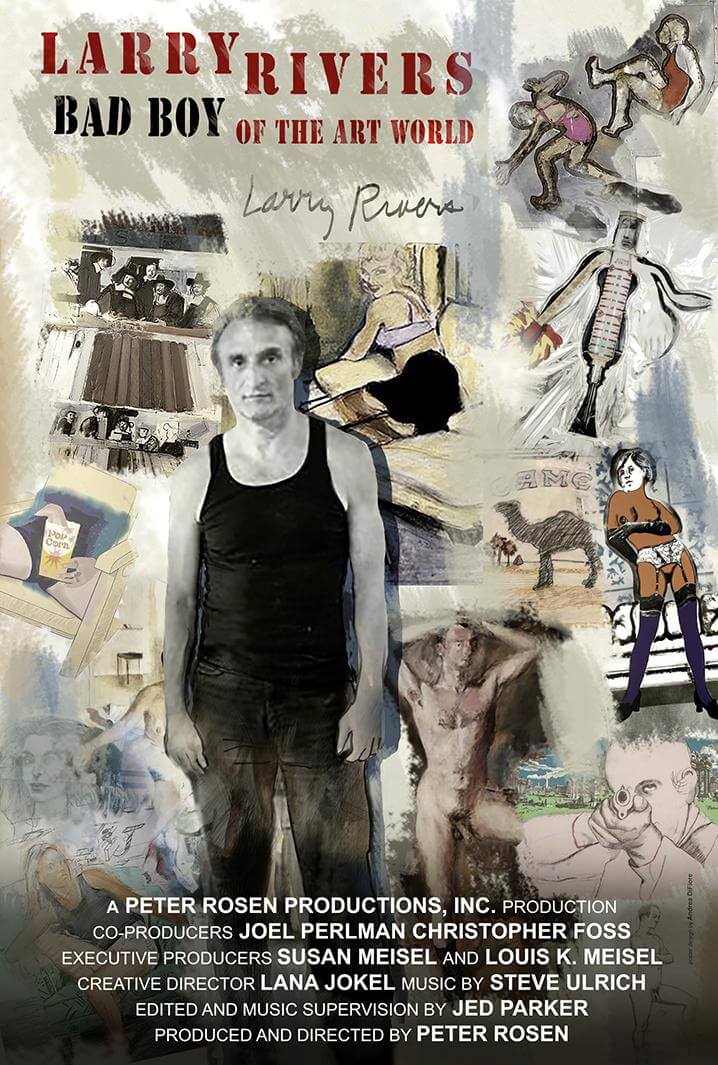

A new documentary film about Rivers and his complicated legacy screened Wednesday at Sag Harbor Cinema, and it’s as much a testament to his important role in shaping the direction of modern art, as it is an unvarnished look at a complex character who never shied away from saying or doing the uncomfortable thing or expressing himself in ways that might, during this particular time, have him erased from the annals of art history.

Larry Rivers: Bad Boy of the Art World begins with Rivers saying to a woman he’s interviewing, “I have a feeling that this thing might turn into an orgy. Do you feel that could possibly happen?” followed shortly by a scene of the young painter holding a gun to his own head, and then to his son explaining today, some 20 years after Rivers’ death, that people thought his father was an asshole, and “people still think he was an asshole.”

It’s an introduction to the once drug-addled, art provocateur who slept with men and women, played jazz and shot smack with Charlie Parker and Miles Davis — and bridged the gap between the Abstract Expressionist movement of the 1950s and the Pop Art revolution led by Warhol in the ’60s.

Rivers, who died in 2002, also spent five years chronicling the growth of his young daughters’ breasts, starting when they were just 11 years old, for a controversial 1981 film called Growing. As Bad Boy of the Art World attests, this artist was not an entirely sympathetic character, and he and Growing in particular have been the topic of much heated debate and vitriol.

And so, whether one feels Rivers was making a legitimate art film, or exercising so-called perverted fantasies by filming his own daughters (who said he never touched them inappropriately but were nonetheless traumatized by his actions), should all of his contributions be denied? Bad Boy of the Art World attempts to answer this question and get to know the man at its center.

Before delving into his work in any significant way, the movie, directed and produced by Peter Rosen (co-produced by Southampton sculptor Joel Perlman and Christopher Foss, with executive producers Susan and Louis K. Meisel), lays out all of Rivers’ lasciviousness and arguably troubling choices, including the people he hurt and those who loved him — many of whom were one and the same.

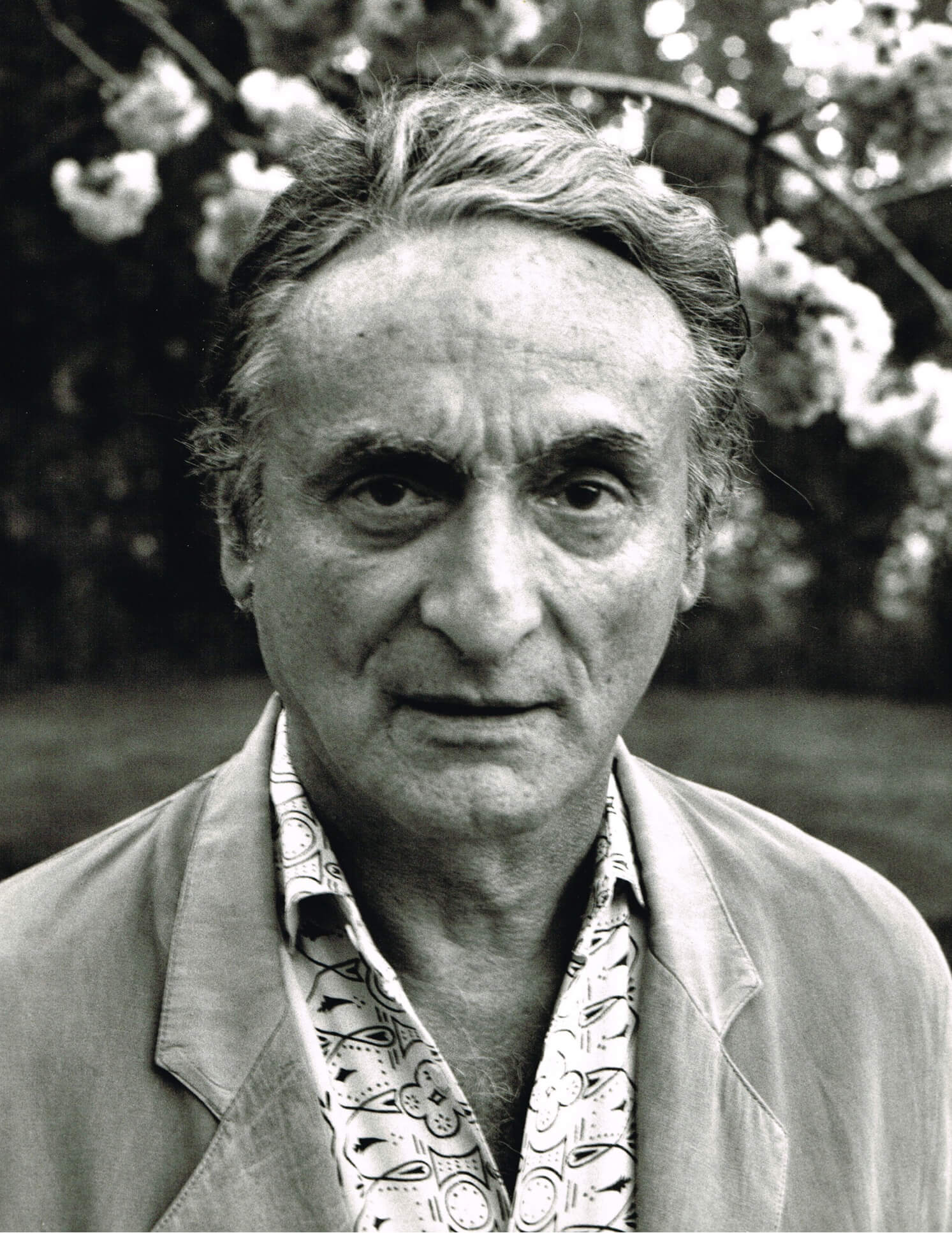

“All good documentaries ought to have some kind of structure like that where there’s a subject who has a problem or hurdles to get over and eventually is redeemed, or there is some overcoming the hardships,” explains Rosen. “In Larry’s case, we really did find there was some sort of a redemption once we interviewed the older daughter, Gwynne, because I think it’s very, in a sense, moving at the end when she kind of forgives him all of his transgressions.”

The film looks at many of Rivers’ greatest works — including his portrait of the last Civil War veteran on his deathbed, and his full-frontal nude painting of poet, critic and MoMA curator (and Rivers’ lover) Frank O’Hara wearing nothing but a pair of boots, which shocked the art world in 1954 — among other dazzling pieces, but it stays light on the technique talk.

“There are many really boring films out there about artists, and they’re just about the artist and his or her technique: How do you apply paint to canvas and what are the colors they’re using? That can be pretty deadly in a documentary,” explains Rosen, who instead made an entertaining film throughout.

“Once we established his character, then I thought I could get away with a second act which is really about his contribution, a very important contribution, as one of the two or three really most important American artists,” the filmmaker adds, while acknowledging that Rivers’ unapologetic persona and his most divisive film, Growing, run the risk of overshadowing his achievements as an artist.

Rosen says North Haven artist Eric Fischl, who participated in a panel after Wednesday’s screening (and whose memoir is also called Bad Boy), spoke directly to this, even before the event. “He says it’s sort of dicey to say certain things nowadays, but he looks at Larry as, as he calls it, a breath of fresh air in today’s environment of people not being able to express themselves, worried about being canceled, all that woke stuff that’s going on,” the filmmaker recalls, adding, “I think it’s a very good time to release a portrait of someone like Larry Rivers.”

He says he has been working on Larry Rivers: Bad Boy of the Art World on and off for more than 10 years, but now feels like the right time to finish it.

“We finally decided to try to finish now because the time seems to be right to bring out certain issues that really center on something as simple as free speech, free expression in Larry’s case,” Rosen continues. “Five years ago, I think this film may have gotten ignored or not even considered in any way. It seems to me, things are opening up a little bit, people are looking at all kinds of different ideas and perspectives on our culture. It’s probably a good time to release it, just to create discussion and just to create the dialogue about that. … I think we’re kind of breaking away from the dogmatic thinking that’s been out there in the culture, so it will be interesting to see how this film will be received.”

Speaking before Wednesday’s screening of Larry Rivers: Bad Boy of the Art World, Rosen said the Sag Harbor Cinema event would be something of a test run for his movie, which is not 100% complete. “We just wanted to test the waters and we thought Sag Harbor is a great community to do that in,” Rosen says, explaining that, at this point, the film has no distributor and he can only say, “It will be released sometime in the future.”