After Death, Artist Linjie Deng Lives New Life with Honesty & Pride

Born in China in July 1992, gay New York artist Linjie Deng also died in July 1992, at least according to his death certificate. With his adolescent life forced to remain a secret in his home country, Deng came to the U.S. with a commitment to living his new life as openly and honestly as possible, resulting in opportunities to showcase his multimedia portfolio in esteemed shows like the Hamptons Fine Art Fair and Art Basel Miami Beach and to raise funds for the causes dearest to him.

While China’s one-child policy, in effect 1979 to 2015, would allow families with two children to avoid penalties in rare circumstances, three children was unheard of. With two older sisters in the Deng family, young Linjie couldn’t officially exist. “In order to keep my family safe and alive, I had to die on paper and live a lie,” Deng says. “I could not go to school because I cannot have a Chinese citizenship. My parents hid me from the police in their storage and wouldn’t let me call them ‘mom and dad.’ They told me that if anyone asks, I’m not a part of the Deng family.”

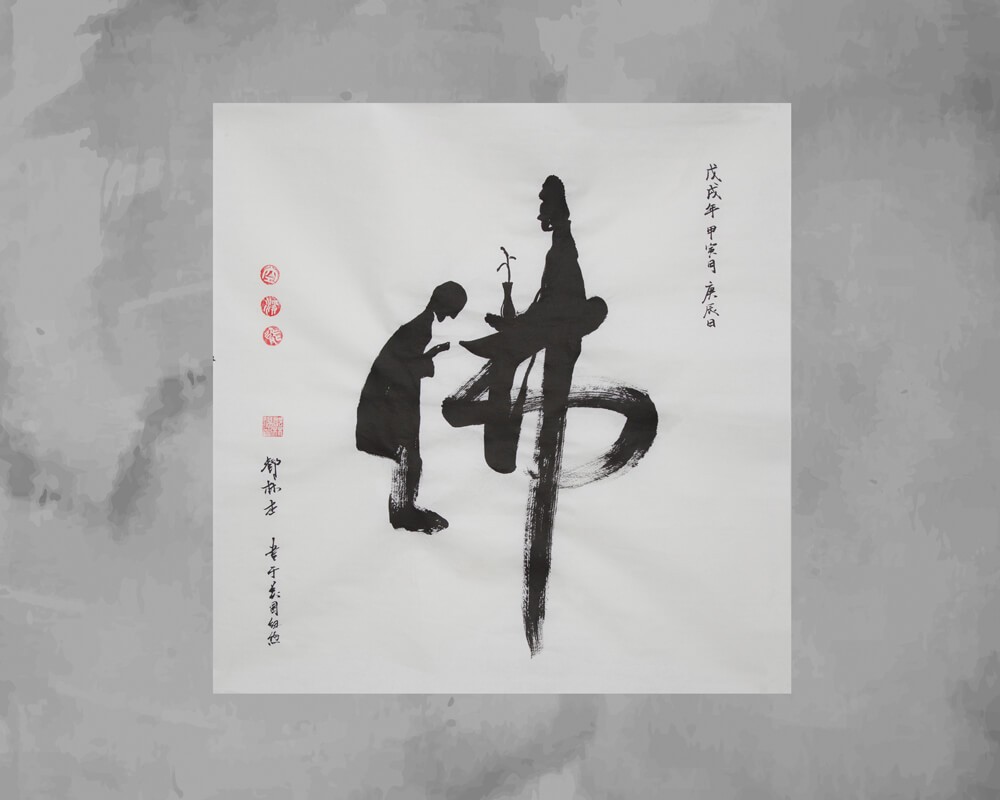

Encouraged to never speak, 6-year-old Deng discovered a loophole to both honor his parents’ wishes and finally “voice” his truth. Using the pen brush and paper provided to him by his parents, busy fireworks vendors, he would sit quietly in a packing box practicing calligraphy, writing the same sentence every day: “‘Hi, I’m Linjie Deng.’ This was the only way I could tell the world who I am,” he explains.

Deng was able to attend Beijing City University in 2011, and in 2015, he decided to leave behind his life as the secret “unnecessary child” and redefine himself at the School of Visual Arts graduate school in New York City. “It’s both scary and exciting, but I get to decide who I want to be because no one has ever met me before. I can create my own identity,” he recalls, adding, “Later on, I realized that part of my new identity is gay.”

In order to pay tuition, he had to begin selling his Chinese seal and calligraphy artworks. He made $80,000 in one week.

Calligraphy was initially a method of protest for Deng, but as he developed his own spin on the ancient art form, he saw it as a way to bring people together, whether or not they can read Chinese script. “I decided that I’d like to do some art without the translation,” he says, alluding to his calligraphy pieces featuring human silhouettes. “I think if people can feel my art without reading the language, there is less of a filter for my audience.”

From Chinese seals and calligraphy, Deng expanded to a number of other art forms and mediums, including abstract ink art, watercolors, acrylic paintings, installations and one particularly bold performance art piece.

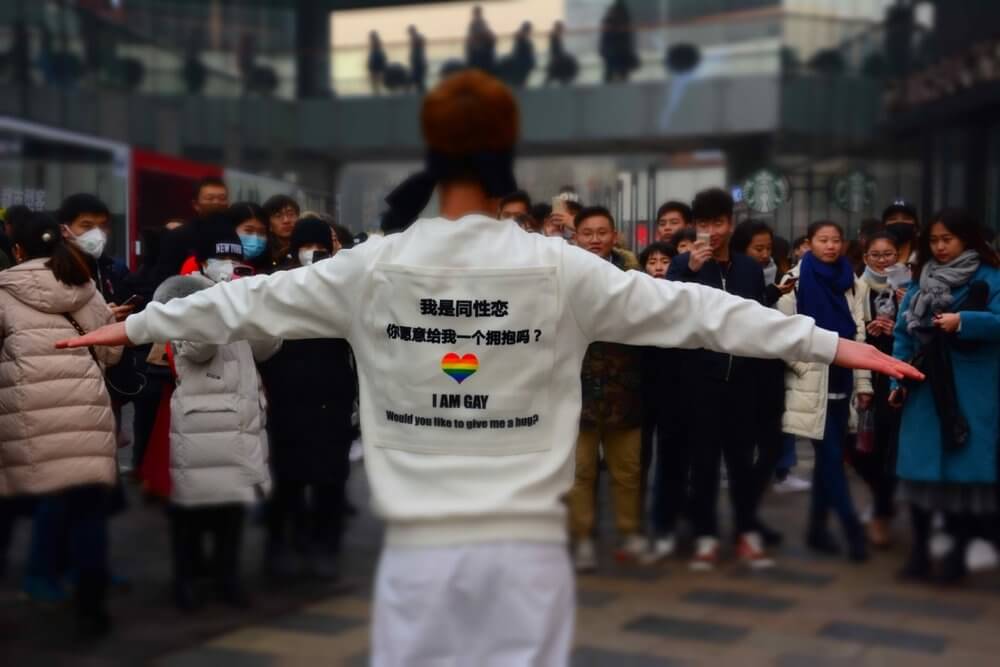

On January 1, 2017, he returned to China to stand blindfolded in Beijing Square, wearing a white jacket that read, “I’m gay. Would you like to give me a hug?” in Chinese and in English. With a camera recording the cultural experiment, he nervously waited to find out what onlookers would do. In the hour before police asked him to leave, he averaged about one hug per minute from supportive young women, with one girl hugging him a second time at the request of her boyfriend, who was worried he’d be labeled as gay if he approached Deng himself.

“There are over 30 million gay men in China, and that’s like Canada’s entire country population, but 90% of Chinese gay men have to fake it by marrying a woman in order to make their parents happy,” Deng estimates. “They build a life on a lie, but I don’t want to live in a lie again.”

As the recording of Deng’s performance was going viral on Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo, the content was restricted for the use of the word “gay.” He responded with the #Togayther movement, where he challenged fellow Weibo users to record videos of themselves answering the questions: What would you do if your child was gay? The first week’s 500 #Togayther videos snowballed into nearly 400,000 responses, Deng recalls, commenting, “The government and the social media company can keep a few people quiet, but they cannot keep everybody quiet.”

His multimedia art gained traction with collectors and galleries, and in 2020, he was invited to participate in that year’s virtual Hamptons Fine Art Fair. “At that moment, I had no idea what the Hamptons is,” he shares. He has since attended the event in person every year, and, as one of the few young Asian artists represented at the fair, he’s proud to be “bridging the culture gaps” through his art. “I want to see people’s reaction about the culture, about my art,” Deng adds.

Through the Hamptons Fine Art Fair and similar events, Deng has had the opportunity to meet several American parents, many of them same-sex couples, who have given fulfilling, healthy lives to girls displaced by China’s former one-child policy, a fate he was thankfully spared. Inspired by these families, he honored the gay parents of straight children and the straight parents of gay kids in his “Superhero Super Gay” painting. “You are your own superhero, and if you’re super gay, that’s OK,” he says of the piece.

Many other paintings in Deng’s portfolio incorporate a rainbow Pride flag motif and have proven popular with both queer and straight collectors. Recently, he donated one such painting to the Dan’s Papers Out East End Impact Awards event, which auctioned it to raise funds for LGBTQ+ healthcare services at Stony Brook Southampton’s Edie Windsor Healthcare Center and at Sun River Health.

Deng addresses numerous social issues with his art. In March 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, he was the victim of a hate crime at the 86th Street subway station on the Upper East Side. A man called him a “f___ing yellow” and shoved him to the ground.

In response, Deng created six artworks, “all yellow because they called me a f___ing yellow,” which the Carlton Fine Arts gallery on Madison Avenue displayed in a solo show titled Asian Art SPA. All the proceeds from that show went to Think! Chinatown, a nonprofit organization helping the Asian community to stand together.

“I think that as an Asian artist, art is my best weapon, and my artwork is a solution to help the American people,” he says. “That makes me feel the most proud.”

One of the most rewarding elements of being an artist, Deng shares, is that he can see people’s true selves. “When I have art fairs like in the Hamptons, I stand in my booth, and I don’t talk to everyone every time. When they walk into my booth, I like to see their faces,” he explains. “I’m watching their ’emoji’ because I think that with people’s body language, the emoji never lies. With one eye, one reaction, I can tell whether they like it or hate it. I like that part. … That’s why I like Hamptons people, they’re nice and honest. They like your art, they buy it. They don’t like your art, they just walk away or take a photo.”

One project that tested the extent of people’s honesty with Deng is an experiment called “Dream Tattoo,” where he asked passersby in Bryant Park to tell him their biggest dream and he’d make them a tattoo reflecting that.

“They’d tell me that their dream is to become a writer or a singer or to be rich, then I’d translate their dream in Chinese, write it in calligraphy with an ink pen brush on their hand, and take their photo covering half their face — so half American face, half Chinese tattoo,” he remembers. “When people participate in that project, they’re very honest. They consider me a tourist artist. They think I’m from China — come here one day, gone the next day. Like, ‘I’ll never see you again in my whole life, so I can be honest with you one time,’ so I get a lot of funny and interesting answers.”

The next big project for Deng is a simple one: to digitize his art portfolio.

“Every time I say goodbye to my artwork, I only have one photo, but I never take a high-resolution photo or scan my artwork. That means that in the future, I will never get a chance to publish my catalog because I don’t have good-quality digital versions,” he says. “Now, before I do any new projects, I’m starting to document everything. After I do all the digital scanning, I’m thinking about releasing a digitalized art catalog, and a published version in the future.”

This way, his art will live on.

To see more of Linjie Deng’s art, visit linjiedeng.com and follow him on Instagram @linjie_deng.