By The Book: A “Tail” As Old As Time

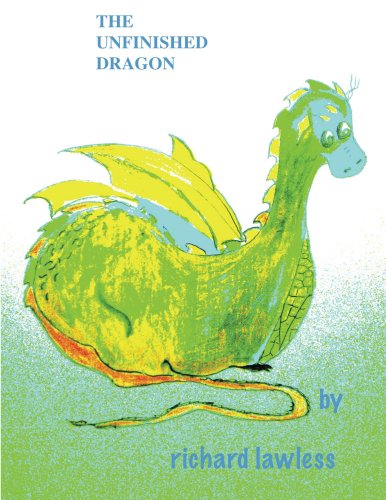

It’s hard to believe that the children’s book The Unfinished Dragon (CreateSpace) and the two sequels it spawned, Camembert and Brie, have had only a kind of underground existence, making their way by word-of-mouth or through a chance meeting with the author, Richard Lawless. Lawless is also an artist and he lives in East Hampton. The charming Edward Sorel-like illustrations that adorn the books exhibit a wit, whimsy and grace that match the prose. The stories, delightful and clever, exhibit an intuitive understanding that good children’s narratives invite a willing suspension of disbelief while touching seriously—but softly—on themes of loss and dread. Lawless also provides a soupcon of levity for knowing adults who are likely reading along with their young charges. They’ll recognize the occasional nod to them, as when a hawk named Sid tells Camembert the friendly dragon that he used to be an agent, but was miserable, had stomach trouble, finally got out, and now is “free as a bird.”

The Unfinished Dragon (26 pp.), the first in the series, shows from the start its literary age-appropriate bona fides. It begins dramatically with Camembert’s father, Bertram, an old warrior dragon, commanding his young son to “Breathe fire!” Next paragraph: “I can’t.” Lawless knows his fairy tale myths, Oedipal and otherwise, and how to use simple diction and reigning clichés to critique gently the expectations of contemporary culture. The father, a dragon of great repute, tells his young son Camembert that he expects to retire, wants to fish, sail, play golf, swing in the hammock, but “how can I ever stop touring and signing autographs if my only son can’t carry the torch of Dragonhood…the family flame?” Alas, Camembert’s a pussy cat, so to speak, unlike typical fire-breathing dragons and certainly unlike the dragon toughs he sees hanging around playing hooky and showing off their red hot flames. He likes to write poetry, and he fears that because he’s different and doesn’t want to scare enemies or frighten little children, he’s a loser. He doesn’t want to be like his father, but wants his father to like him.

The old warrior expects compliance. Camembert’s mother Beatrice, though more understanding, is lovingly cavalier. As he leaves to practice fire breathing in the desert, she calls after him that she thinks he’ll make a fine tennis player. Camembert slinks off, but cannot do the flame thing. Meanwhile, dragon-slayers arrive. But so do friends. These include Sid, the hawk, and also a coyote and an ant, all of whom instinctively take to Camembert, seeing his good heart. Lawless uses these reappearing diverse creatures as a unifying device as well as a sympathetic Greek chorus, signaling that Camembert is not alone.

Well, of course, there’s a turning point but it’s not a simple-minded one. After much practice and perseverance (kids, there’s a lesson here), Camembert breathes fire. Does he ever! He can’t stop. It becomes excessive (kids, there’s a lesson here, too). He comes home anyway to show his parents his accomplishment, but alas, they are gone—death in the story is nicely finessed—Bertram and Beatrice have become mountains. Now Camembert really comes into his own, as does Lawless—The Little Dragon That Could takes nourishment from the stars and becomes a dragon whose exhalations are colors of the rainbow, glorious colors and different shapes, different qualities, some with music. In a later story, when Camembert is himself old (and wise), the theme turns on the universal quest to be special, which Lawless relates to the uniqueness of being the only one of one’s kind, as are we all as individuals, and so we are each extra-ordinary.

It’s unlikely that a young ’un will know what “camembert” refers to, and maybe some older folk won’t know more than the fact that it’s the name of a cheese, but such is the book’s appeal that it prompts a click onto Wikipedia where camembert is described as a “soft, creamy, surface-ripened cow’s milk cheese,” first made in the late 18th century at Camembert in Normandy, and that it resembles brie. Now of how many children’s stories can it be said that they prompt research!