Shinnecock Voices: 'Killers of the Flower Moon' a Film of Indigenous Torment from White Perspective

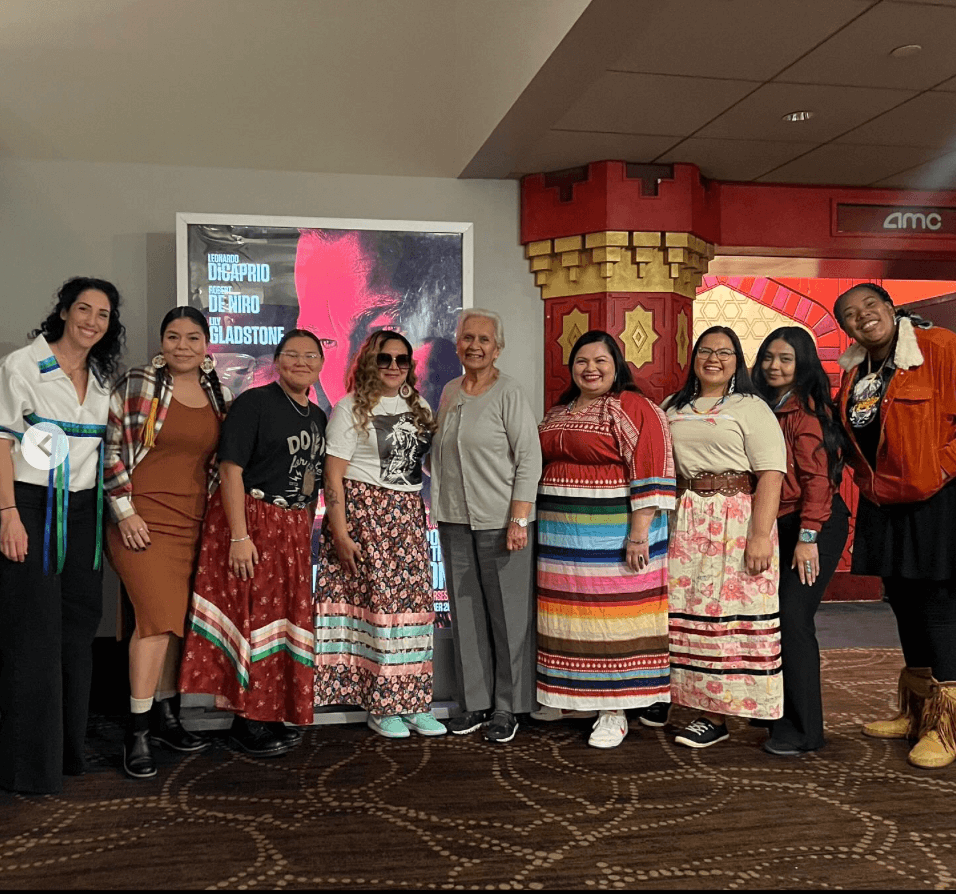

Ahead of the wide release of the anticipated Martin Scorsese film Killers of the Flower Moon, Paramount Pictures orchestrated events welcoming Native communities from all over the country to attend free screenings. Local theaters, like the Sag Harbor Cinema, invited Indigenous guests to experience the film first-hand. At the screening at AMC Lincoln Center in NYC — where I attended — ribbon skirts, wampum pieces and beadwork bedecked Native attendees. It was a poignant exhibition of support for a movie whose cast, still steeped in a tense SAG-AFTRA strike, were contractually barred from walking the red carpet.

The palpable ripple of pride felt on the carpet was tangible, underscoring the transformative moment we’re getting to witness. With the success of shows like Reservation Dogs, Dark Winds and Rutherford Falls placing Native characters at their narrative core, and Hulu’s Prey having smashed streaming records, Indigenous stories have been gaining traction like never before. How would Hollywood handle the chilling saga of the Osage people’s torment, and could these characters in Killers of the Flower Moon transcend mere plot devices?

From 1920–1925, 60 headright-holding Osages were brutally murdered during the grim chapter known as the “Reign of Terror,” which has been the subject of a number of literary works. These headrights granted their holders a share of the Osage mineral estate’s quarterly funds, while simultaneously making them targets.

The 1934 book Sundown by John Joseph Matthews, an Osage, and the 1990 book Mean Spirit by Linda Hogan, a Chickasaw, use the murders as the atmospheric backdrop for their literary creations. Dennis McAuliffe Jr., an Osage, wrote The Deaths of Sybil Bolton based on the murder of his grandmother, whose death, initially attributed to kidney failure, was revealed to be the result of a gunshot wound.

David Grann’s 2017 book Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI was the book that Martin Scorsese used as his primary source material. When initially developing the script, and using Grann’s book as a guide, Scorsese’s first draft explored the investigations of the murder and the role they played in developing the FBI.

However, in a New Yorker interview, Scorsese discussed the moment when he and Leonardo DiCaprio embarked on the rewriting process. He recalls the conversations, saying, “You realize, of course, that means we go in the center of script, rip it open and change everything and tell the studio you want to play the other guy, and we’re going to go this way, and Lily (Gladstone) is great, and we’ll rewrite the whole thing, which is what we did.” Despite the film’s runtime of three hours and 26 minutes, there was a lot that was excluded.

While there has been a swell in Native characters represented in Hollywood, society has moved beyond mere tokenism. As conversations around representation continue to gather momentum, one-dimensional portrayals on screen no longer suffice. While each of the Native actresses (Lily Gladstone, Tantoo Cardinal, JaNae Collins, Cara Jade Myers and Jillian Dion) plays their role with incredible tenacity and strength, the script omits the true level of fear that ravaged the Osage Nation, and the film’s central family.

Instead, the audience is shown the lengths to which white characters went to plunder the wealth of the Osage Nation. The film expends ample time detailing the orchestration of these heinous acts, but the magnitude of the losses incurred remain disproportionately under-explored. In this narrative, the Osage Nation is relegated to a backdrop, rather than the central focus.

Representation in Hollywood has historically been filtered through a white lens. With a majority of above-the-line jobs — director, cinematographer, writer, producer — occupied by white people, inherent biases persist. Scorsese crafted a beautiful film. However, inadvertently, the film consigns the Osage Nation to the periphery rather than casting them in the central role of their story.

This sentiment was echoed by a consultant and Osage tribal member, Christopher Cote, who was present at the Oklahoma premiere and shared the following, “Martin Scorsese, not being Osage, I think he did a great job representing our people, but the history is being told almost from the perspective of Ernest Burkhart (played by Leonardo DiCaprio), and they kind of give him a conscience and kind of depict that there’s love. But when somebody conspires to murder your entire family, that’s not love. That’s not love, that’s beyond abuse.” While love is a central theme of the film, it is not a love story.

In an era where narratives featuring people of color are increasingly represented in cinema, softening the depiction of white characters’ cruelty diminishes the truth of the impact on BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and other people of color) bodies left in racism’s wake. One cannot help but ponder the emotional impact of a character who was able to confront the full weight of his abhorrent actions. Instead, DiCaprio adopts the persona of a dopey everyman, suggesting that his situation befalls him rather than acknowledging his active role in the demise of a family he should have been protecting.

Underplaying white characters’ cruelty diminishes the effects of racism on the minds and bodies of marginalized communities. The undeniable fact remains that a group of white men conspired to deny the Osage people the wealth they rightfully posted and were willing to go to any lengths for that wealth’s acquisition. Countless racist acts have been committed in this country when a person of color behaves as if they have the same freedoms of white people.

If we continue to avert our gaze from this harsh, yet indispensable reality, cinematic depictions of race relations will remain superficial fixes, incapable of instigating the transformative surgery required to heal the wounds of our nation.

Andrina Smith is a storyteller, writer and performer whose work frequently explores race and the ways we can increase Shinnecock representation. She currently spends her time between Brooklyn and Southampton.

“Shinnecock Voices” is a monthly column in which citizens of the Shinnecock Nation share stories and opinions and discuss the projects and campaigns they’re working on, to allow readers an inside view into their incredible community.