Montauk Lighthouse Revisited: The Fresnel Lens Returns

When I first came to the East End of Long Island as a teenager in the 1950s, the Montauk Lighthouse was off limits to the public. A chain-link fence put up by the U.S. Coast Guard blocked the way.

Passage was possible through a checkpoint however, if the armed officer let you through. But only the military was welcome. The Cold War was underway. Soldiers were all over Montauk. We had a U.S. Air Force base, a radar station, a fighter jet spare parts facility, a submarine facility and a U.S. Army base with big guns pointing out to sea.

Among other things, I’d been told that the Coast Guard was measuring the distance between the tower and the edge of the cliff once a year. The lighthouse, built in 1796 by order of George Washington, had originally stood 300 feet from the cliff’s edge. But erosion was ongoing. By 1956, the lighthouse stood only 96 feet from the edge.

As a result, when in 1960 I started The Montauk Pioneer newspaper that would later become Dan’s Papers, I began calling the Coast Guard to ask how much cliff had been lost from the year before. In 1969, the distance was down to 68 feet. I did some calculations.

“Seems the lighthouse will be falling into the sea in 1986,” I told the officer.

“Well, it won’t matter,” he said. “We’ve just received an order. The lighthouse will be abandoned and replaced by a steel tower 300 yards further inland.”

“Abandoned?”

“By the end of this year,” he said. “And probably torn down.”

I was shocked. The lighthouse was a historic monument. This couldn’t be allowed to happen. And so, I called upon the public to do something about it. I formed the Save The Montauk Lighthouse Committee. It had one member: Me. And as chairman, I invited everyone to a vigil on August 30, 1969 in the parking lot to light up the night.

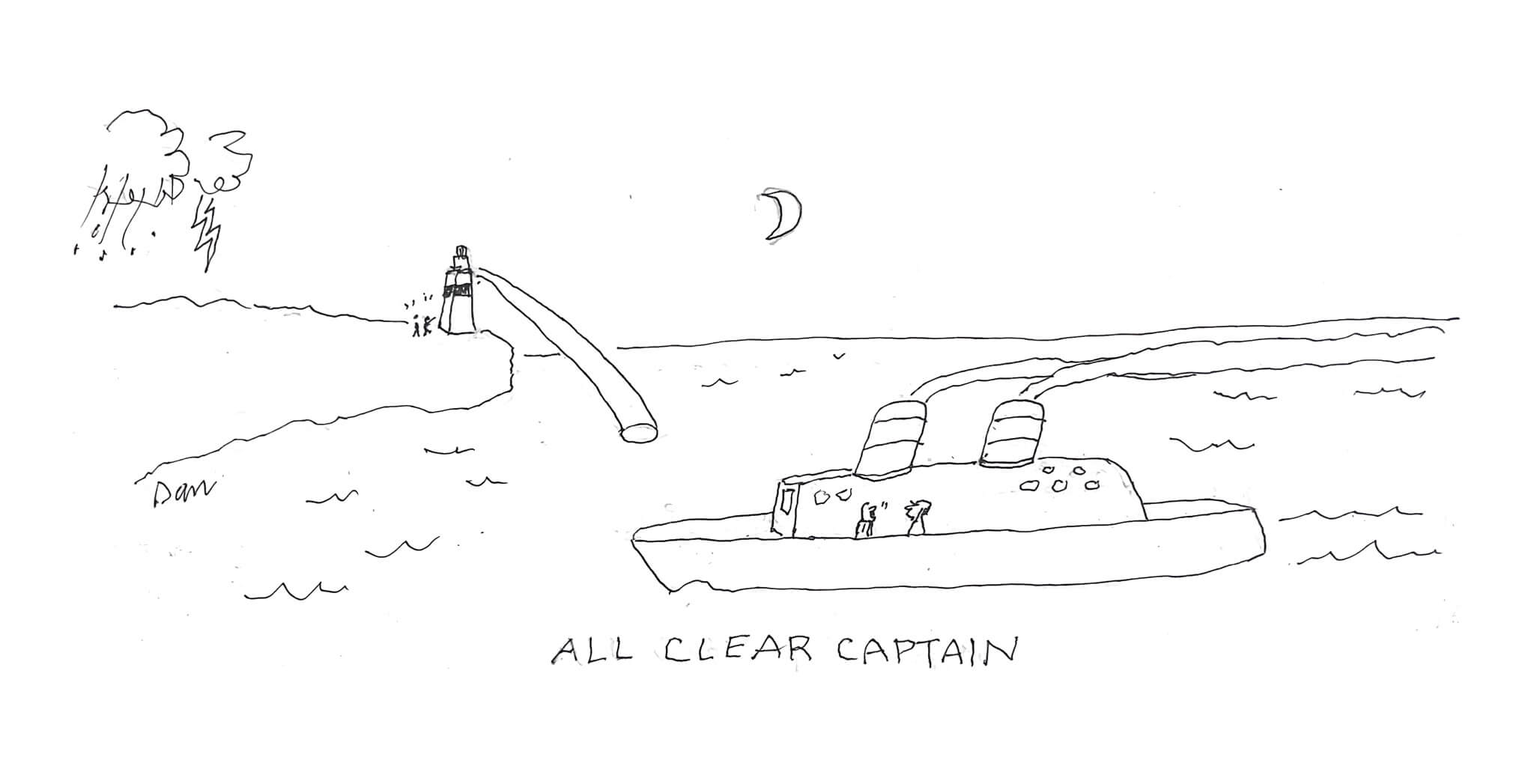

According to police, more than 4,000 people came and they held up lanterns, flashlights, torches, batons, spotlights and beacons. It was the largest protest ever held in the Hamptons. For an hour, the people stood vigil. The Bay Shore Fife and Drum Corps, with 10 flaming baton twirlers, marched and sang. A fire truck served as a speaker platform and among those speaking was Perry Duryea, a Montauk lobsterman who became the Speaker of the Assembly in Albany. Offshore, Montauk fishing boats sat at anchor with their lights blazing. Nobody at the Coast Guard could miss seeing this.

A few days later, a woman named Giorgina Reid appeared at my office. She and her husband had bought a home in Rocky Point that faced Long Island Sound. A storm had come through and 10 feet of cliff, their front lawn, had tumbled down into the sea.

“We had to stop this,” she told me. She researched how to do it. And she’d written a book, which she showed to me. It was possible, using a method invented in Japan, to cover a cliff face with terracing and seagrass. It would stop erosion. And it stopped the erosion in front of her home. The book was How to Hold Up a Bank.

“I can do this at Montauk Point,” she said. “I will bring volunteers. Can you arrange that?”

Was she crazy?

“Nope,” I said. Then I said, “But the chain-link fence does leave a few feet of grass unprotected at the top of the cliff. You could walk across the rocks below, climb up, and do it. Maybe they won’t stop you. I’ll write about it.”

So, she did that, and the Coast Guard didn’t stop her. What was going on? She and her volunteers came every weekend, hammering in wooden steps and planting seagrass. And the Coast Guard did nothing. But they did have a request.

“They want me to get insurance indemnifying them in case somebody is injured,” she told me.

The following year — this was now two years in — Coast Guardsmen, off duty, started bringing supplies and provisions to her on the cliff face. And now the admiral wrote that the Coast Guard was scrapping the idea of a steel tower and committing itself to the restoration of the lighthouse.

Five years later, the Coast Guard invited myself and Giorgina Reid (still out there!) to a luncheon in our honor at Coast Guard headquarters on Governors Island. There, they presented us with awards. Mine declares “appreciation” for what I had done. Hers notes “accomplishment.”

I have a photograph of the two of us, flanking a bemedalled admiral, smiling as we displayed our awards.

In 1987, the Coast Guard leased the property to the Montauk Historical Society so it could be made into a museum. Inside, today, a whole room is devoted to Reid for what she did, year after year, to stop the erosion there.

I hadn’t been to the lighthouse in a long time. Last Monday afternoon, however, my wife and I drove out to watch the sun, setting over the trees to the west of the lighthouse, bounce sparkling diamonds of light off an antique Fresnel lens that a giant construction crane had put up there on November 6.

This historic lens had been gifted to the Montauk Lighthouse by the French in 1903 and remained in use until 1987 when the Coast Guard, as part of the handover to the Historic Society, replaced it with a modern electric beam that produced less light but required very little maintenance. The museum could then operate without daily Coast Guard intrusion.

Now, however, in a major change, a huge crane has put the Fresnel lens back up top. The Montauk Historical Society will do the necessary daily maintenance.

And so, last Monday at dusk, a crowd of visitors applauded as the more powerful ancient beam was lit for the first time, blazing its light a full 15 miles out into the night.

Dozens of people need to be thanked for making this happen. Not the least of whom is Dick White Jr., the chairman of the Historical Society, who was present at that long ago protest I conducted.