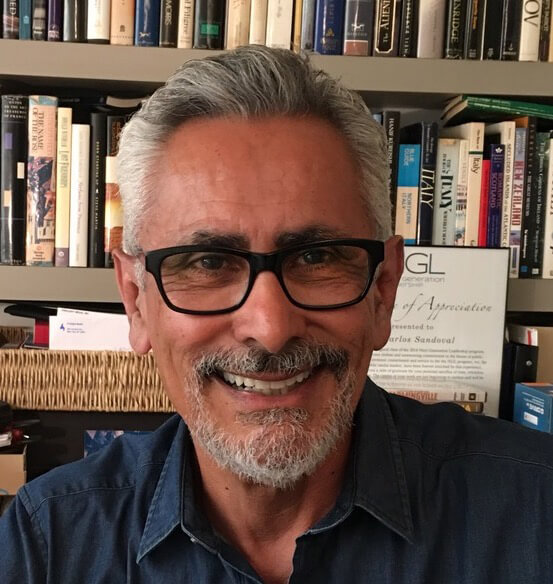

Being Gay Saved My Life: Filmmaker & Writer Carlos Sandoval

In the melting pot of America, millions of individuals are raised at an intersection of cultures, from multifaith households to multiethnic families. For Carlos Sandoval, an Emmy-nominated filmmaker of Mexican American and Puerto Rican descent, the cultural crossroad with the biggest impact on his life and career is his identity as a gay Latino.

Growing up in a Southern California barrio, he could feel one culture pulling him toward safe careers with financial security and a bit of machismo, while his other half yearned to embrace his creative artistic side. Graduating from Harvard College and the University of Chicago Law School, he decided on a practical life as a Manhattan lawyer.

Then an HIV diagnosis began to drain his vitality and he sought respite with his partner on the East End. Unsure of how much time he had left on Earth, he grew determined to create his “swan song” and began drafting a variety of written works with the potential to live on after his death.

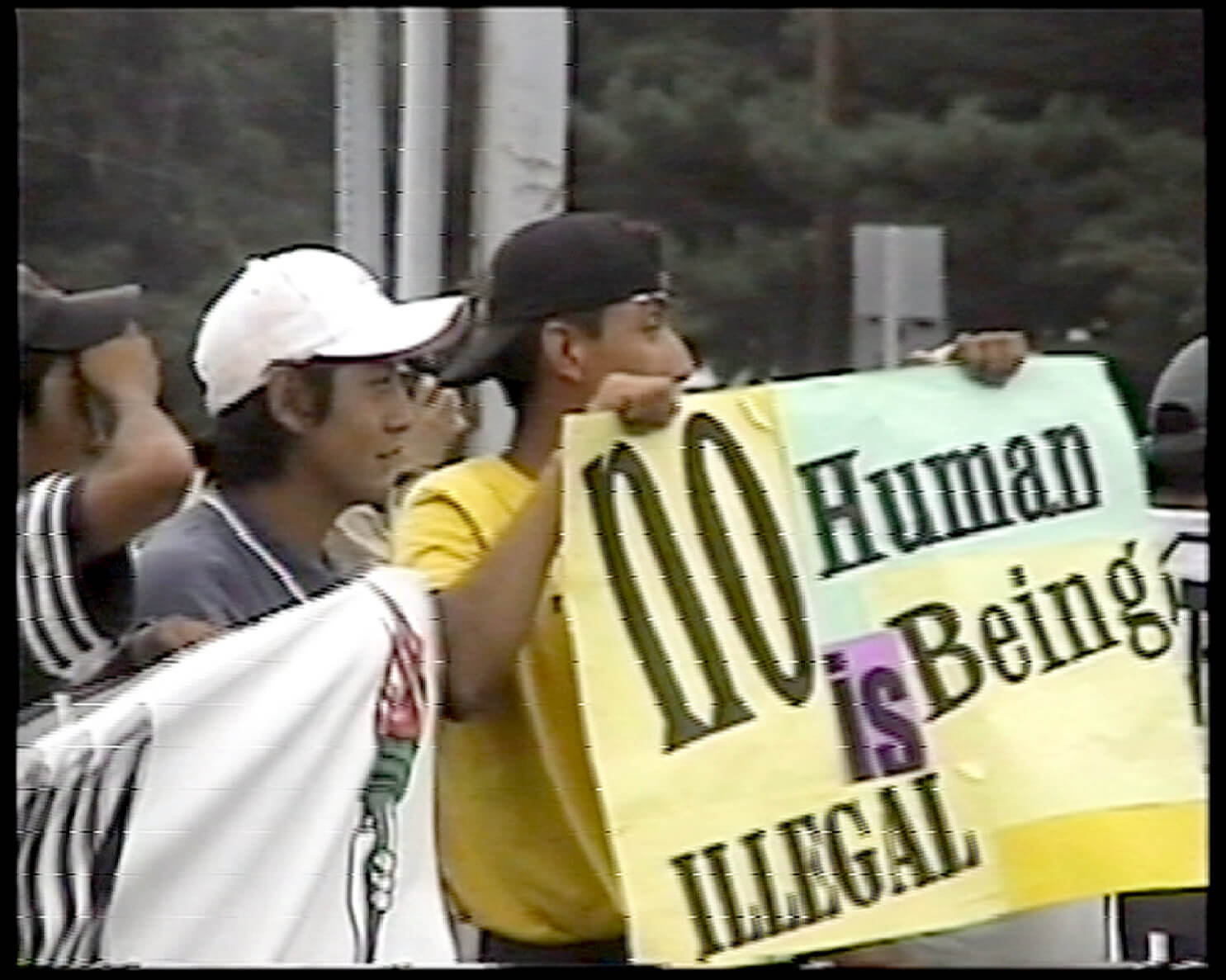

To Sandoval’s amazement, in 2003, he and Catherine Tambini premiered Farmingville, a 78-minute documentary that they directed and produced, for which Sandoval lived and worked in the Farmingville community for nearly a year to observe first-hand the racial tensions between Latino immigrants and longtime Farmingville residents.

The film won the 2004 Sundance Film Festival’s Special Jury Award and inspired Sandoval to continue his unplanned filmmaking career with nationally broadcast documentaries including The State of Arizona and A Class Apart. With his swan song fulfilled, and then some, and his HIV under control, a 71-year-old Sandoval is now shifting his focus back to his pre-filmmaking writing and teaching at the Columbia School of Journalism.

We had the pleasure of speaking with him about his fascinating story.

A Conversation with Carlos Sandoval

How do you feel that your identity in terms of sexuality, ethnicity, et cetera has influenced your career opportunities and decisions?

It was very lucky that as a kid from a barrio in Southern California, I ended up at Harvard. … I did very well the first two academic years, but something happened in my junior year, and I had to take some time off. I went into a bit of a depression. I think part of that was the delayed reaction to the culture shock; I didn’t know how the world functioned. …

As a graduate from an Ivy League school, I didn’t know to what extent doors could be open to me or how to open them. I decided to get into book publishing because I loved reading. I always treasured them, but I didn’t think I could be a writer.

So I thought I might be able to help in the birthing process by becoming an editor of Latino writers. I didn’t realize that to live in New York on a publishing salary, you had to have a trust fund, which I did not. So I wanted to get away from that. I had several really fun jobs, including being a member of the U.S. delegation to the U.N. and working the policy think tank.

Eventually, I felt like I could no longer be the bright, young thing, so law school was the route to go.

In terms of my ethnic identity, I felt at that point, in my naivete, that the issues of discrimination were taken care of. The stories had been told about our position in history and the like, so there was no need to address them anymore. Little did I realize how long that struggle would be. I didn’t want to ghettoize or pigeonhole myself by focusing on Latino themes, and yet many years later, that’s where I would end up going.

In terms of my sexuality, I don’t think that it played as much of a role in my career, professional choices, other than the fact that I felt that there were certain things that I might’ve tried to do but didn’t do because of the stigma around being gay at that time. And by that, I mean politics. The possibility of going into the public light while having to cast that in the shadow was not something that I felt would be possible to do.

But I also have to say this: Being gay saved my life. The de facto segregation that existed in Southern California at that time meant that you were not supposed to be intellectual or creative if you were Hispanic, but I was able to express that side of myself (through the exploration of my gay sensibility). … And that sensibility made me want to get away from home and strive for more.

I think that had I been a straight kid, a straight Latino kid, my life would’ve been much more circumvented, but being gay set me apart in a way that I wanted out and might not have otherwise.

In the ’60s, people were rebelling. In some ways, my rebellion was conformity and mainstreaming myself because I didn’t need to “rebel.” My entire life was a rebellion. For me, it was about how do I succeed or find the world that I want to live in. And that world was one that was much more conventional from the one that everyone was rebelling from. I was looking to musicals when everyone was looking at rock. The macho world, I didn’t want. It was punishing to me. The gay side of me counteracted that macho side.

After leaving your life as a Manhattan lawyer, how did the East End help you to heal and to redirect your focus into writing?

I was able to take time off and really use our place (in the Hamptons) as a retreat where I could spend time in solitude, and that allowed me to do a lot of experimentation. My writing went on to take several forms, including a couple of plays — one that got a reading at the Jungle Theater in Minneapolis — and some essay writing …

One of the pieces that I wrote was for the Long Island section of The New York Times. I came across the incident of the hate-based attempted murder of two Mexican day laborers in the town of Farmingville. The headline, (stating that the assailants) wanted to kill some Mexicans, struck me, and I was deeply hurt, offended and angered by that. I felt that something should be done. … To really move the dial emotionally, I felt that a story would be the best way to go, so I decided to begin tackling a documentary, but I only planned to get it off the ground. I didn’t expect to end up co-producing it.

Not only was there an actual creative space that the East End gave me, but also being on the island attuned me more to what was going on around Long Island. That combination of things led to that first piece … and the way that I approached that was kind of nuanced and balanced, applying my University of Chicago law and economics background to that and trying to see who actually was bearing the cost and reaping the benefits of the day laborer population that had descended on the town. So that all ended up becoming the basis for the film.

Had you experienced anti-Hispanic sentiments on the East End around that time?

At the time, no. I remember having written — I think around 1998 or 1999 — a piece in which I talked about a trip my boyfriend and I had taken to Southern California, reflecting on the discrimination that I experienced when I was growing up there in the ’50s … then coming back to the East End and seeing the beginnings of the Hispanic community developing there and thinking, “Wow, we have an opportunity for a different model here.

This is a more welcoming community.” And I thought that we were going to sidestep that. Indeed, some of that existed on the East End, particularly out in Montauk with the initial influx of immigrants that were staying in the Montauk hotels. And there were reactions like the “volleyball wars” that took place; workers were playing volleyball, and they’d have these huge gatherings in Springs, and neighbors complained about it, but I think it got managed fairly well. It didn’t hit that kind of extreme that it did in Western Suffolk, although I do have to say that I would see smaller bits of microaggression, not so much directed at me, but some of the Latino immigrants at that time.

Once you had settled into the quieter East End life, how did you decide to not only kickstart a Farmingville documentary, but to immerse yourself in that community during a time of high racial tensions?

I wish I could say it was an active decision, but it just was an evolution. I think that seeing that (attempted murder headline) prompted me to action. I felt I couldn’t let that stand. …

I met with Nigel Noble (who won the 1982 Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Subject), who was supposed to be our original director, and he put me in contact with Catherine Tambini. Nigel couldn’t take on the project (right away), as he had other commitments.

I rented a place in Farmingville meanwhile to really get a sense of community, and I lived there for about nine months. At a certain point it became clear that Nigel was not going to be able to participate in the project, so Catherine and I took over. I call myself sort of an “accidental filmmaker.” I really did not expect to be able to do that … but I guess I’ve really become a storyteller.

I never thought of myself as a creative person, and I think that was partly because growing up as a working-class Latino in the Southwest at that time, the expectations were limited. I did not think that I had what it would take to be creative. Plus, I needed to be practical in terms of really making some money. I didn’t think I could be a writer. I didn’t think I could be a filmmaker. I didn’t think I could be creative, in part because it was not an option.

We in the Hispanic community weren’t the creators, so it took me a long time to discover that aspect of myself. Now I find that it is what I enjoy … to the point that I teach. I’m an adjunct professor at Columbia University, the School of Journalism, and advise each year a couple of students in their thesis project and try to impart what I’ve learned.

With Farmingville thought to be your swan song due to your HIV diagnosis, how has your prolonged health affected your sense of purpose or outlook on life?

It has made me more comfortable in my skin. I feel I have a legacy. That was my greatest fear: to pass without having done something or created something. Not to be boisterous about it, but I really felt Farmingville did that. … People have written their master’s thesis about it. People still come up to me and say, “I taught that film in my classwork,” or, “I studied that film at graduate school.”

And people said it was important in terms of development of policy. It was the first film of that era (to address) the immigration debate. It was a seminal work in many ways. Our approach was more balanced and nuanced … and the approach seemed to be kind of innovative. I feel like I contributed something with that. I stand a little taller, walk a little prouder, and feel that I have my voice to do more things.

To go back to the HIV for a second, it’s not guilt that I feel, but I often contemplate the fact that — whereas so many others, including dear friends, couldn’t reach their potential — in some ways HIV, or the time that I had to take away from work because I thought I was at death’s door, gave me the opportunity. I feel very blessed that I’ve been able to find myself and not indirectly because of the virus.

In your personal experience, how has the stigma around HIV evolved since you were diagnosed?

It’s night and day. Well, there was the external stigma and the internal stigma. The external stigma was other people’s fear of the disease. Luckily, I was not ill or had to deal with those very early days of being quarantined in hospitals and being isolated in that way. But I obviously did not speak out. I was not open about it because I didn’t want people to be put off by me. On the other hand, the internal stigma was if I needed to take a blood test, I always felt obligated to tell whoever was taking the test, “Be extra careful because I’m HIV positive.” And it made dating difficult. …

Now it’s changed. The support that I found among friends and family, well friends more than family … but in terms of friends, they’ve been incredibly supportive throughout. Now mind you, I don’t go around announcing it to everyone. It’s a matter of fact now, but I do feel that things have changed remarkably.

What do your writing and filmmaking endeavors look like today?

I’ve pulled back from filmmaking because I’m 71 years old now. It takes a lot to do the kinds of films that I used to do. I’m lucky in that now I can be the wise film man. I do more story consulting and that sort of thing.

I’m trying to turn towards writing more because my great ambition in life is to write a family memoir or history of my family. It’s something that I first got attracted to when I was in college, and I’ve not let go since. In fact, when I started writing in that period after leaving (my career as) a lawyer, I tried to write this family memoir. I didn’t quite know how to deal with it. That’s what led to the play, and the screenplay that I wrote. …

My writing really stemmed from that impetus of wanting to write that family memoir; that’s what I’ve been wanting to do. A lot of stuff keeps getting in the way of it, but I’m hoping that now I’ll be able to turn to it. … I (recently came) across an approach on how to cover 600 years of my family’s presence in what’s now the United States in a way in which I think I can touch on a couple of touchstone stories that will allow me to skip generations and centuries but lead to a coherent arc.

I’ve done a lot of research towards it, and I’m hoping that now the storytelling chops that I developed through filmmaking will inform my ability to tell these stories as a writer.

Looking back on what you’ve accomplished in your life and career thus far, what stands out as most fulfilling or personally rewarding?

I wish I could be profound about that, but it’s really my filmmaking and all my children there. I think it’s because of what I’ve seen from audiences when the films are shown. Farmingville was the catalyst that gave way for dialogues around a very difficult issue. Unfortunately, the issue continued to unravel. (The documentary) didn’t save the world, but I do think that it helped ameliorate situations in certain communities.

And again, it’s been taken up in schools and the like with another one of my films, A Class Apart, which was an American experience about the Mexican American civil rights movement and a case that was argued successfully by a group of lawyers before the Supreme Court just before Brown v. Board of Education.

It’s been incredibly gratifying to present it to audiences and have people come up to me in tears afterwards and say, “Thank you. This is my family’s story. This is what my parents talked about,” or, “This is what I experienced, and I’ve not seen myself on the screen before, so thank you.”

It was deeply moving to see that. To be able to give someone a moment to validate themselves, I think is the greatest thing that I’ve accomplished.