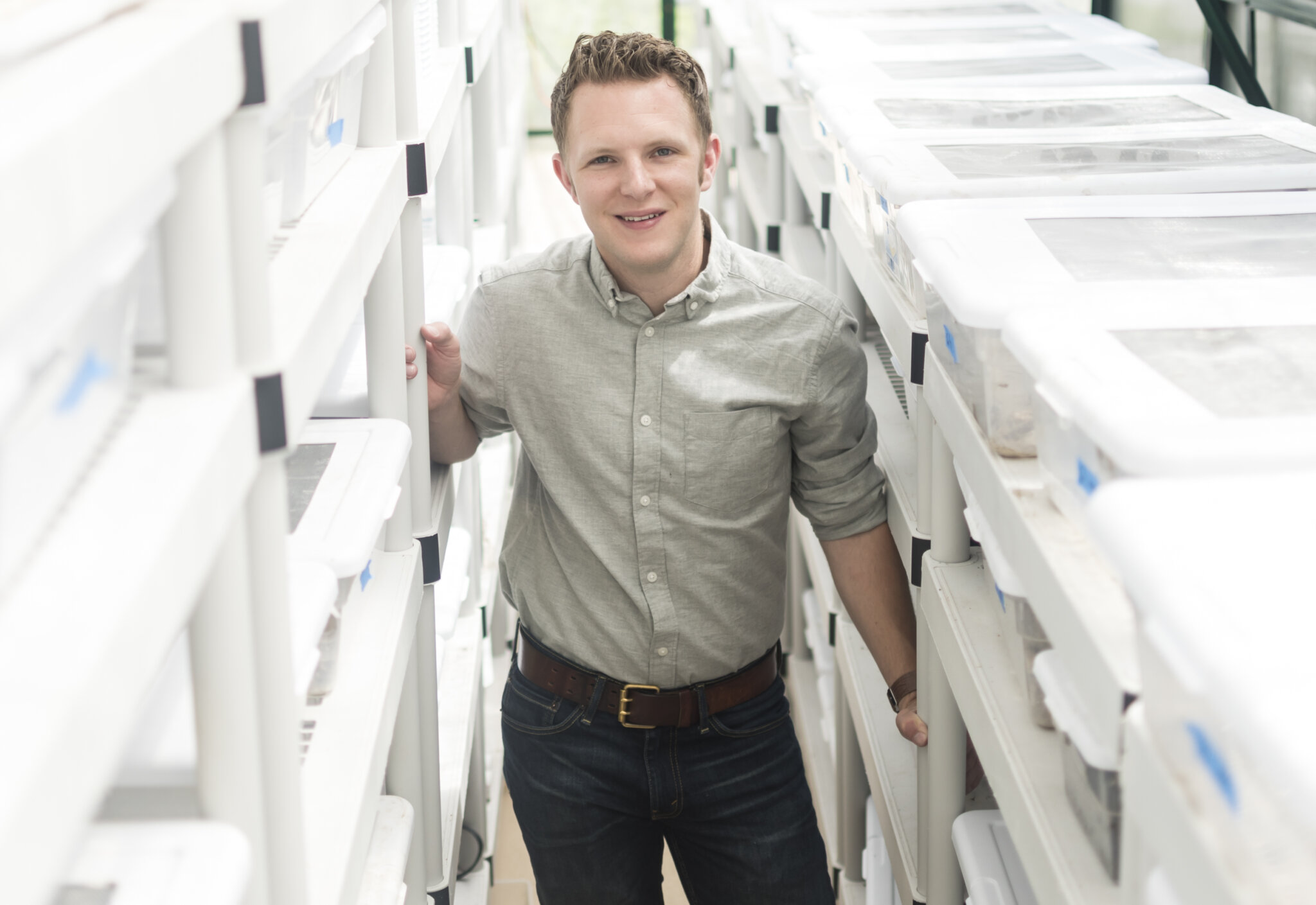

Talking Petit Gris with Peconic Escargot Head Snail Wrangler, Taylor Knapp

We hope you’d be forgiven for thinking all escargot are the same. A snail is a snail and, at your favorite French bistro, the little guys usually end up on your plate in the form of a vehicle for butter and garlic and a baguette. There’s a snail farmer in Cutchogue, however, who’d like to have a word with you.

“If you eat snails at any restaurant in the U.S. and it didn’t come from us, it means it came from a can or [they’re frozen],” says Taylor Knapp, the owner and ‘head snail wrangler’ of Peconic Escargot, the first and only USDA-sanctioned snail farm in the country.

“No one was raising snails,” he says. “Ten years later, we’re still really the only guys in the game, and I’m talking about the country.”

Prior to Knapp’s leap into artisanal snail-farming, the scarcity of live, domestically-raised snails came down to the fact that Petit Gris (or little grey snails) have been deemed an invasive species by the USDA, which does not permit them to be grown openly on a farm. That is, until Knapp pitched the government a way to keep the hungry critters safely contained — and they listened.

“Petit Gris breed quick and they’re voracious eaters and they will eat it till it’s gone. They can do a lot of damage,” Knapp says. “We still raise them in dirt … but in a greenhouse, in pens, with locks and closures and screens, like indoor beekeeping, or mushroom growing.”

The typical escargot you get from a traditional French bistro, says Knapp, has never been fresh. It almost always comes out of a can imported from Asia or Europe.

In contrast, his North Fork-raised Peconic Escargot is killed-to-order and has a limited freshness window; it’s also markedly more expensive at $68 per (shelled) pound than, say, your average $12 can of snails imported from France. The difference, however, is in the flavor. First introduced to North America by Europeans in the 1850s, the species itself is raised to be eaten and enjoyed, even without the aid of garlic and butter sauce.

“The petit gris that we raise are smaller than your typical canned snail, but that’s a good thing! These are the bay scallops of the snail world — sweet and tender,” says Knapp.

He breeds roughly 50,000 to 70,000 of the snails per year in his 300-square foot greenhouse. Though he primarily sells wholesale to restaurants, Peconic Escargot is available in stores and online; he also sells escargot caviar and oven-ready snails in two types of butter sauces.

“A lot of our restaurant clients, most of the time they’re not French restaurants, because [French restaurants] are often so used to using the canned products,” says Knapp. That leaves him primarily selling to high-end eateries across the country, including NYC’s Semma, a highly-rated Southern Indian restaurant.

Part of his job as a snail farmer, says Knapp, is to teach chefs and home-cooks that snails are not to be feared; they’re just a simple form of protein.

“You can do whatever you want with a snail, it’s just an animal,” he says. “It tastes like a mushroom and has the texture of a clam. Whatever you can do with mushroom flavor and clam texture, you can do with snails – tacos, grits, ramen, dumplings. The sky’s the limit because it’s a very versatile ingredient.”

Knapp should know since he’s also the chef at much-loved Greenport pop-up restaurant PAWPAW. Inspired by the Indiana native’s culinary travels, the food at Paw Paw has roots in Knapp’s work at Noma — the New Nordic restaurant in Copenhagen consistently named among the world’s best — and all his ingredients farmed, fished, and foraged are sourced on the North Fork.

“The food your eating at PAWPAW is not Scandinavian, but we’ve taken those lessons that I’ve learned at Noma and applied them to the way we’re doing things here, which is if we can find a local flavor to season a dish with, we always go for that,” says Knapp. “So, instead of putting vanilla in a desert, it may have sassafras from the sassafras roots that we dug up in Southold. There are incredible flavors that come from our own backyard, so there’s a lot of foraged ingredients … the idea [at PAWPAW] is that it’s very fresh and it’s not over-manipulated.”

Located inside the Lynn Beach House in Greenport, the menu at PAWPAW “is always a surprise and changes weekly,” according to the website. A sample posted online includes an eight-course tasting menu with dishes like a savory duck egg custard and black pearl oyster mushroom with spruce bough oil, snail caviar, and wild garlic mustard; blackfish with grilled broccoli and beach plants, mint, pistachio and casteltravano olive; short rib of beef braised with juniper and bayberry; and a fall stew of charred eggplant, black garlic, and sunchoke.

Specific escargot-centered dishes (made with Peconic Escargot, of course) can also be ordered, but only as a supplement. There are two seatings at PAWPAW on select Saturday nights throughout the year of no more than twenty guests. Knapp’s next two dinner experiences are scheduled for December 9 and 16. Reservations are required.

Originally intended to be a short-term pop up, the former chef and founder at Jedediah Hawkins and First and South has found a year-round audience with PAWPAW’s intimate dinners. “I wanted to keep cooking, I said, ‘we’ll do a couple of these and call it a day, it’ll be a fun little thing to do,” says Knapp. “Anyway, we’ve been doing it for eight years … people keep coming in and they really enjoy it and we have fun with it. Plus, I don’t think there’s many restaurants that can say they’ve never served a piece of meat or fish that isn’t from Long Island.”

Learn more about Peconic Escargot at peconicescargot.com.