East Hampton Doctor Helps Lead Lyme Disease Testing Breakthrough

Ongoing research into Lyme disease using a locally sourced biobank appears to be on the cusp of a major breakthrough that could change the way we test for the illness, improve efforts for early Lyme detection and offer advancements in various other medical applications.

Dr. George Dempsey of East Hampton Family Medicine, who has been collecting blood and urine samples from East End Lyme patients for the Bay Area Lyme Foundation’s Lyme Disease Biobank since 2014, explains that this new study has found a marker that could detect Lyme earlier than before, while also showing if the illness has been treated.

“If we can show two points in time together — the early detection of Lyme disease and then resolution of the infection — it will be game changer,” Dr. Dempsey says. “We will have a new way to look at how antibodies behave in Lyme but also other diseases affecting the immune system.”

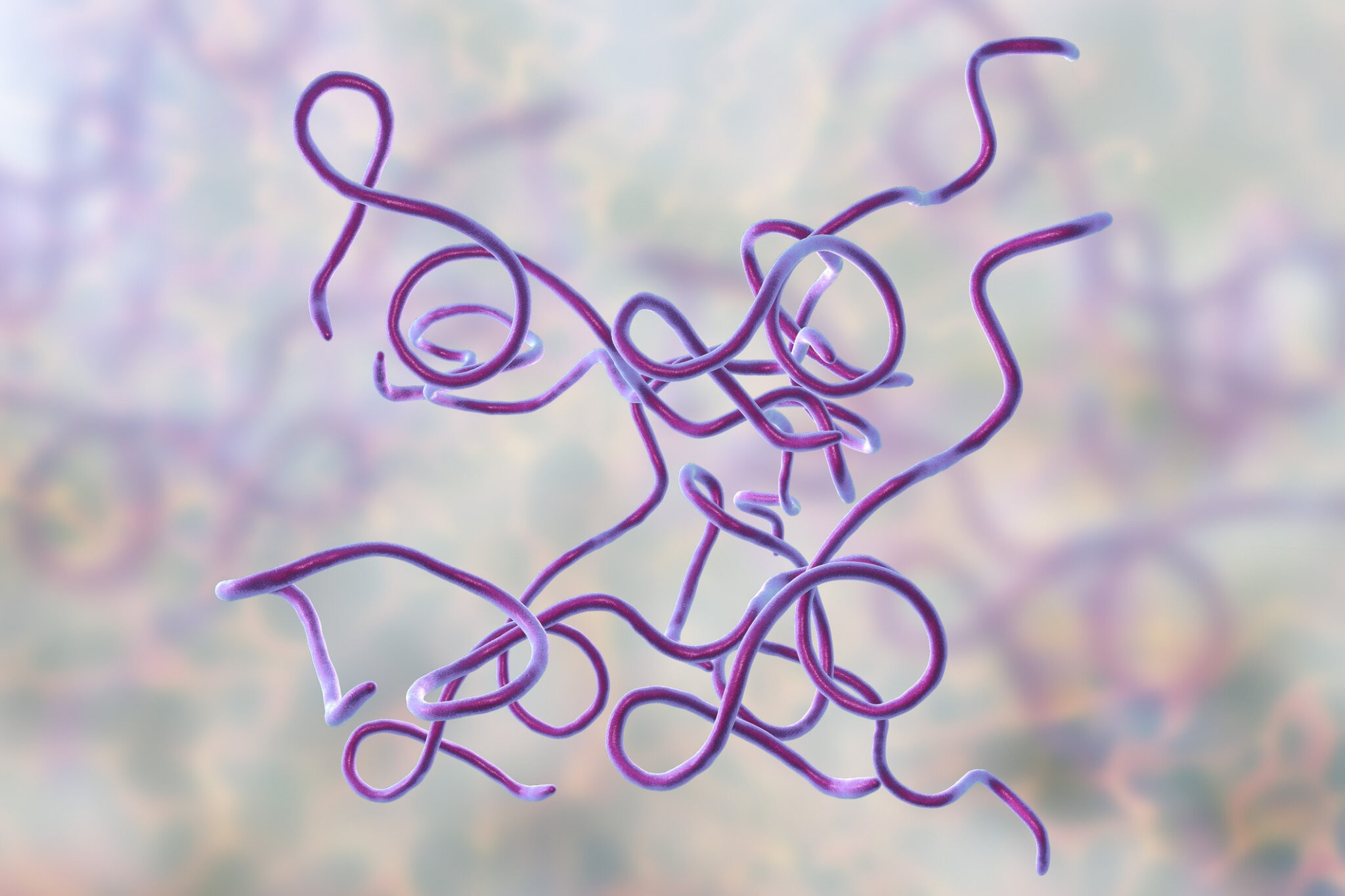

Right now, the only FDA-approved diagnostic for Lyme disease measures antibodies that are developed to fight the offending bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi, but these antibodies aren’t detectable for several weeks following transmission through a tick bite. And the quicker one can get treatment, the better it is for defeating the illness, which can be debilitating and difficult, or even impossible, to cure in late stages.

“When it’s early, at the stage of a rash, the antibodies have not developed yet. It’s a two-stage process. There’s the initial, primary response and there’s the secondary,” Dr. Dempsey says. “The primary response is the body just going, hell, something’s not right, and it’s basically kind of shooting in the dark but getting inflamed. Then it’s starting to characterize it — oh, look at this, now I’m going to make an antibody. And that takes a few weeks, so that is why the testing has not been helpful in the early stage.”

At the same time, he points out the value of knowing when Lyme has been eliminated from a person’s body. Since antibodies are the only metric for detection, tests really only show whether a patient has had the illness or not, without revealing its duration or the level of infection.

“By the time you treat it, the antibodies maybe have started to develop, so even though you treated it, the antibodies are there because they were hired, they were recruited,” Dr. Dempsey says, describing why people will test positive for Lyme even after treatment.

Now, however, if this promising study bears fruit, much more information could be gleaned from what they’re calling the “GlycoLyme assay.” According to the study, published in The Lancet, a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal, the authors were able to examine the behavior of certain markers to determine time points of a Lyme infection. It’s published online at the lancet.com for anyone interested in reading the specific science.

“This is deep science, which is actually the whole point of it, what I engaged in with the biobank, was to enable deep science,” explains Dr. Dempsey, who is named among eight authors of “Host glycosylation of immunoglobulins impairs the immune response to acute Lyme disease.”

First recognized from a cluster of children suffering from arthritis in Connecticut in the 1970s, and now in locations around the world, evidence of Lyme disease goes back at least 15 million years, with the earliest example found in a tick fossilized in ancient amber, from long before man walked the Earth. Here it is carried solely by the tiny blacklegged ticks, aka deer ticks, and causes an array of unpleasant symptoms.

Sufferers can experience fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint aches, and swollen lymph nodes. In later stages, these symptoms can become worse, with the addition of severe arthritis, heart palpitations and irregular heartbeat, nerve pain, dizziness, shortness of breath and more.

Patients are often alerted to the infection by a bullseye-shaped rash surrounding a tick bite, which will usually prompt immediate treatment with antibiotics, but not everyone is lucky enough to get a telltale rash. This is why the new testing would be vital.

Dr. Dempsey also hopes this research and the new assay will help resolve some contentious, controversial issues surrounding Lyme. Specifically, he acknowledges the belief, held by many, that the disease can be chronic, with people either blaming Lyme for a range of general, persistent symptoms because they have the antibodies, or blaming these various symptoms on Lyme without presenting any antibodies because the symptoms match and have eluded any other diagnosis or explanation.

“All that stuff is where it gets buggy, and that’s where you could have one person who says you have chronic Lyme, another person says it’s old Lyme, and if someone is feeling bad, is this Lyme just because you have antibodies? Or is it something else?” he asks. “The symptoms are vague, or I just feel lousy. You can’t pinpoint these symptoms very well. Like long COVID — it’s all similar. People just don’t feel right, but we don’t have a way of pinning down the marker that clearly shows that’s what it’s related to,” Dr. Dempsey continues, adding later, “It’s going to give us a lot of insight to a lot of these questions that everyone has. And it might give us a better handle on what is chronic Lyme and not, or who has it or not. It might begin to sort that out a bit better.”

Dr. Dempsey is hopeful that this particular assay may provide the insight into whether people can develop Lyme and not get antibodies long term, whether there is that subgroup of people who do not develop an antibody response. “That’s going to help answer that question, which nothing else has up to now,” he says, noting that in science he’s learned that you must be open to possibilities until the work proves otherwise.

“How else can you tell if someone has chronic Lyme? The only thing else you can do is try to isolate it from the body, try to culture it somehow or find it, and no one has been able to do that,” he says.

Now that the study is published, Dr. Dempsey says it’s time to find private funding, get through the red tape and move ahead with more research and data collection for the biobank.

This summer, Dr. Dempsey will again work with the Drexel University research team, but instead of focusing on early detection, he is exploring resolution of the infection.

“The next step is to get FDA approval and have longitudinal testing. People have been volunteering their blood and urine early in infection and then retesting about a month later,” Dr. Dempsey says. “What we need to do next is have people come in, usually with the rash — some pretty classic symptoms — we treat them, but we also send the labs out to the biobank, and then a month later, and then we would want to do it (again) perhaps a few months later. So then we could see over time how this glycosylation pattern evolves and correlate that with how (patients) are feeling,” he says, explaining that they would also follow any changes from those who continue to have symptoms after treatment.

“We have to get enough samples for the FDA to be satisfied,” Dr. Dempsey continues, acknowledging that the process will take time. “No matter how much money you get, you have to have volunteers,” and, unfortunately, his practice is one of only two sites contributing to the biobank. The Marshfield Clinic in Minnesota has come aboard, but they are still just two sites collecting the important samples, which have already led to exciting innovations, including a French lab that Dr. Dempsey says created a card with a chip in it to be placed over a tick bite using dozens of tiny micro needles to detect the presence of Lyme in the bite.

Each year, some 476,000 new cases of Lyme are reported, and the standard diagnostic misses 60% of cases during the earliest stage of illness, which happens to be the most important time to cure the disease. So new and accurate tests for Lyme disease are imperative if Lyme is ever to be fully understood and defeated.

Dr. Dempsey is looking for people to share samples and take part in this valuable work.

To get involved in the Lyme Disease Biobank, people experiencing symptoms of early-stage Lyme disease, that has not yet been treated or who are in the first 48 hours of taking antibiotics, are asked to donate a small sample of blood and fill out forms reporting symptoms. Participants will receive information on tick-borne diseases, advice from experienced doctors, and tick-bite prevention tips. Contact East Hampton Family Medicine, located at 200 Pantigo Road in East Hampton, at 631-324-9200.