'Montauk to Manhattan: An American Novel' by Thomas Maier - Part 2

Editor’s note: This is the second of a three-part series in which Dan’s Papers will publish excerpts of Thomas Maier’s new book Montauk to Manhattan: An American Novel, published on July 9 by Post Hill Press.

Chapter 2: Tycoons

While waiting for the day’s filming to begin, I thought of how fate had brought me to that remarkable place on the beach, like some aimless Odysseus washed up on shore. I considered myself particularly fortunate given the almost miraculous origins of my novel.

Years earlier, while struggling as a local newspaper reporter, I stumbled across the historical story of Austin Corbin, the nineteenth-century entrepreneur who would become the fictional protagonist of The Life Line.

Bold and ambitious, Corbin was the toast of 1880s’ New York. He projected the same drive and industriousness that inspired Americans to pick up Horatio Alger’s “rags-to-riches” novels. One pundit described the bald, long-bearded, and full-bellied tycoon as “part hog, part shark.” But Corbin’s big dreams and self-aggrandizement caught the public’s fancy.

After attending Harvard Law School, Corbin became a banker, Wall Street speculator, mortgage-lending swindler, plantation owner, resort developer, and, eventually, a railroad man. His ruthless go-getter voraciousness was compared to fellow American tycoons Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould. He partnered with financier J. Pierpont Morgan in various shady enterprises.

Corbin belonged to “that tribe of human monsters who prey upon poor men,” observed one magazine, “who, being influenced by greed, make war upon the weak, regardless of right.”

Unlike some millionaires who hid their wealth, Corbin was happy to showcase his massive mansion. He luxuriated in a gaudy lifestyle celebrated by the press. His fame grew widely, enough for him to be considered one of the leading citizens of his day.

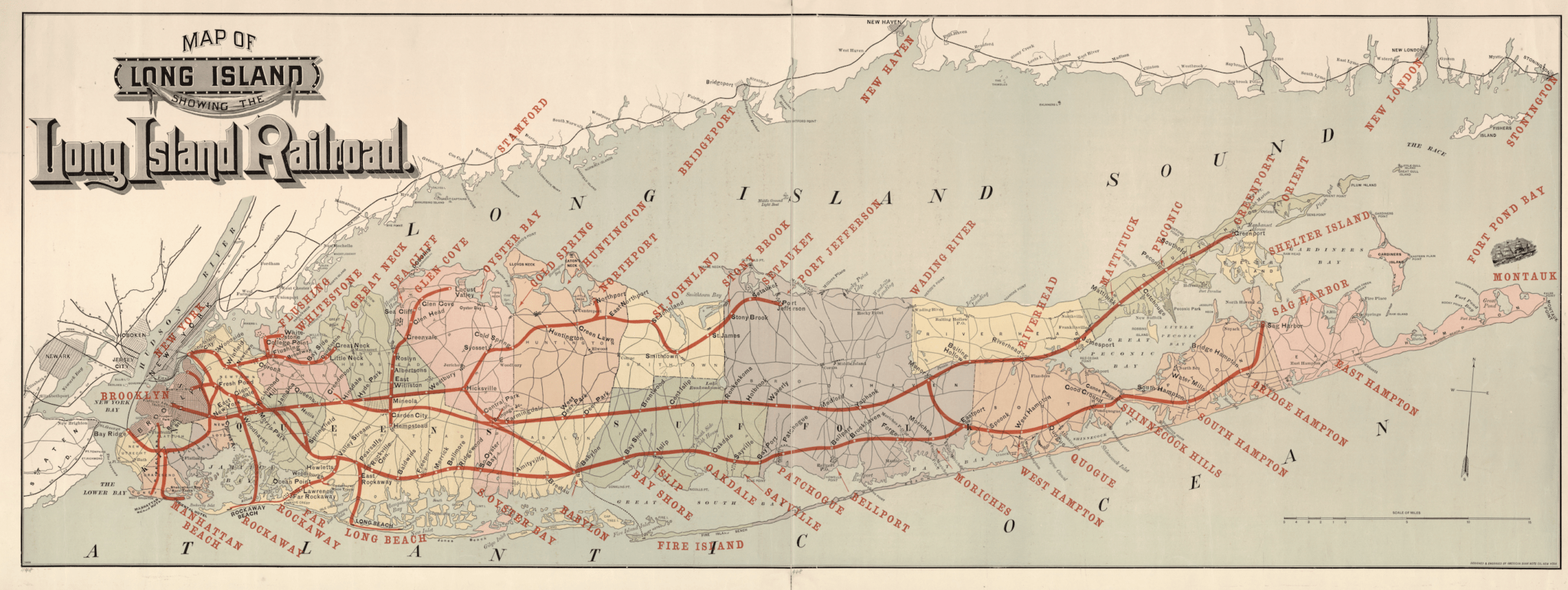

In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur paid homage to him by traveling aboard one of Corbin’s Long Island Railroad express trains to visit his private summer estate. “President Arthur’s Excursion: Speeding Over Long Island at the Rate of About a Mile a Minute” declared a Brooklyn Eagle newspaper headline touting this escapade.

Though a money man with vast interests around the country, Corbin was best known in New York for turning acres of abandoned sand dunes along Coney Island into a popular ocean resort. His stylish seaside hotels, including one called The Oriental with grand spires reaching towards the sky, catered to wealthy white Anglo-Saxon Protestants like himself. He expressly forbade so-called “undesirables” from his door, especially Blacks, Jews, and Catholic immigrants with foreign accents.

Nevertheless, thousands of other New Yorkers came to Corbin’s summertime enclave. They enjoyed sunning themselves along the ocean beach, Jockey Club horse racing, and nightly fireworks concerts at an outdoor ten-thousand-seat amphitheater surrounding a man-made lagoon. Composer John Philip Sousa and his band played “Stars and Stripes Forever.” Elaborate shows reenacted historical events, like Civil War naval battles, and well-known natural disasters like “The Last Days of Pompeii” — enthralling audiences with the kind of grand showmanship that movies would later provide.

For five dollars, thrill seekers could go up in a hot-air balloon, as high as a quarter mile into the atmosphere. They’d be pulled back to earth with a cable after getting a bird’s eye view of all Corbin had created.

Like Buffalo Bill and Houdini, Corbin realized that Americans, along with all the other necessary staples of life, needed entertainment. They wanted escape and amusement — what became the essence of Coney Island. With his high-society resort, he carved a dreamland out of the city’s desert.

“To him New York owes almost all that is good at Coney Island,” The New York Times later eulogized in his front-page 1896 obituary. Admirers like the Times editors took note of Corbin’s Yankee ancestry and applauded the kind of entitlement behind his takeover of tribal lands during his career.

“Long Island at that time was an almost unknown territory to any others than natives,” said the paper of record. Corbin was the first — but certainly not the last — fast-talking New York tycoon to seek his fortune by promoting himself shamelessly in the city’s newspapers.

My novel The Life Line revolved around Corbin’s biggest boondoggle. At his zenith, he envisioned a way to make millions by short-cutting the week-long trip for steamships, square rigs, and schooners between New York City and Europe. Instead of navigating the sometimes-treacherous Long Island coastline of 120 miles, these ships could land in Montauk and travel rapidly into Manhattan aboard Corbin’s private express trains. He claimed his plan would eliminate a day of travel from the Atlantic journey for international passengers and hopefully turn Montauk into another resort haven, the Miami Beach of the north.

Corbin wanted to dynamite the northern bulkhead of Montauk to create a deepwater port where the ships would land. That project alone would be a remarkable engineering feat, proof of his determination to move heaven and earth. But to connect both ends of Long Island with his railroad, Corbin would need the land rights of the remaining Montaukett Indian nation living there peacefully, a proud but diminished people in the Hamptons.

Corbin’s greediness and ambition reflected all the avarice of America’s Gilded Age. Up from their bootstraps, indefatigable men like Corbin seemed born to greatness. “I don’t care to retire — this is my pleasure,” he explained to reporters. “I like to see the machine run, to help it run, and to feel that I am steering it.”

As I learned from research for my novel, Corbin accomplished this shameless land grab of Native American reservations through chicanery and threats of violence. He smoothed over public opinion with full-page ads in all of New York City’s newspapers and billboards, touting his multimillion dollar “Montauk to Manhattan” campaign.

More than a century later, the outrage and opulence of Corbin’s story still resonated with Kirkland. By championing the Montaukett cause, he wanted to be “on the side of the angels,” Max told interviewers, and he appeared convincingly sincere. He took all the proper steps, lest he be accused of “cultural appropriation” — a phrase explained to him by the studio’s lawyers.

After buying the rights to The Life Line, Max hired an elderly Montauk chief, steeped in tribal lore, as a consultant. He also vowed to film some TV scenes on what remained of an ancient Native American reservation, tucked away on Long Island’s otherwise-trendy Hamptons terrain.

“This is all stolen land, Jack, and that’s important to understanding our history,” Max said, stating the obvious to me, as he looked up and down the beach where his cameras were now in place. “It was a brutal genocide — a war of extermination — with thousands of people erased from the map. If we are successful, this production will be the great retelling of the Native American experience. How white men like Austin Corbin ran off with the best part of America and turned the Indians into invisible people in their homeland!”

With his gravelly voice in full roar, Kirkland outlined his plans for transformational glory with our project. “Over-the-top streamers, binge-watching — they are now for us what movies were for our parents. They define our era. I want people watching at home to think about what we did to the Montauk Indians. Maybe get off of the fucking couch and march up and down the street in protest. With all this money Comflix has given us, I want to be like D. W. Griffith — only in reverse — and turn The Birth of a Nation on its head!”

Kirkland’s eyes were aglow, with the fury of a true firebrand. How much of Max’s soliloquy he truly believed was hard to figure out. He was famous for bombast about his productions, part of the marketing campaign he knew was needed in this content-rich universe of on-demand platforms and a clueless citizenry left to its own devices.

Nevertheless, Max was correct about at least one thing: the success of The Life Line depended all on him.