Fund Feud: Shinnecock Rally for Southampton to Preserve Ancestral Lands

Shinnecock Nation members and allies rallied August 5 outside of Southampton Town Hall to urge local officials to use funds earmarked for preservation to protect the tribe’s ancestral burial grounds from development.

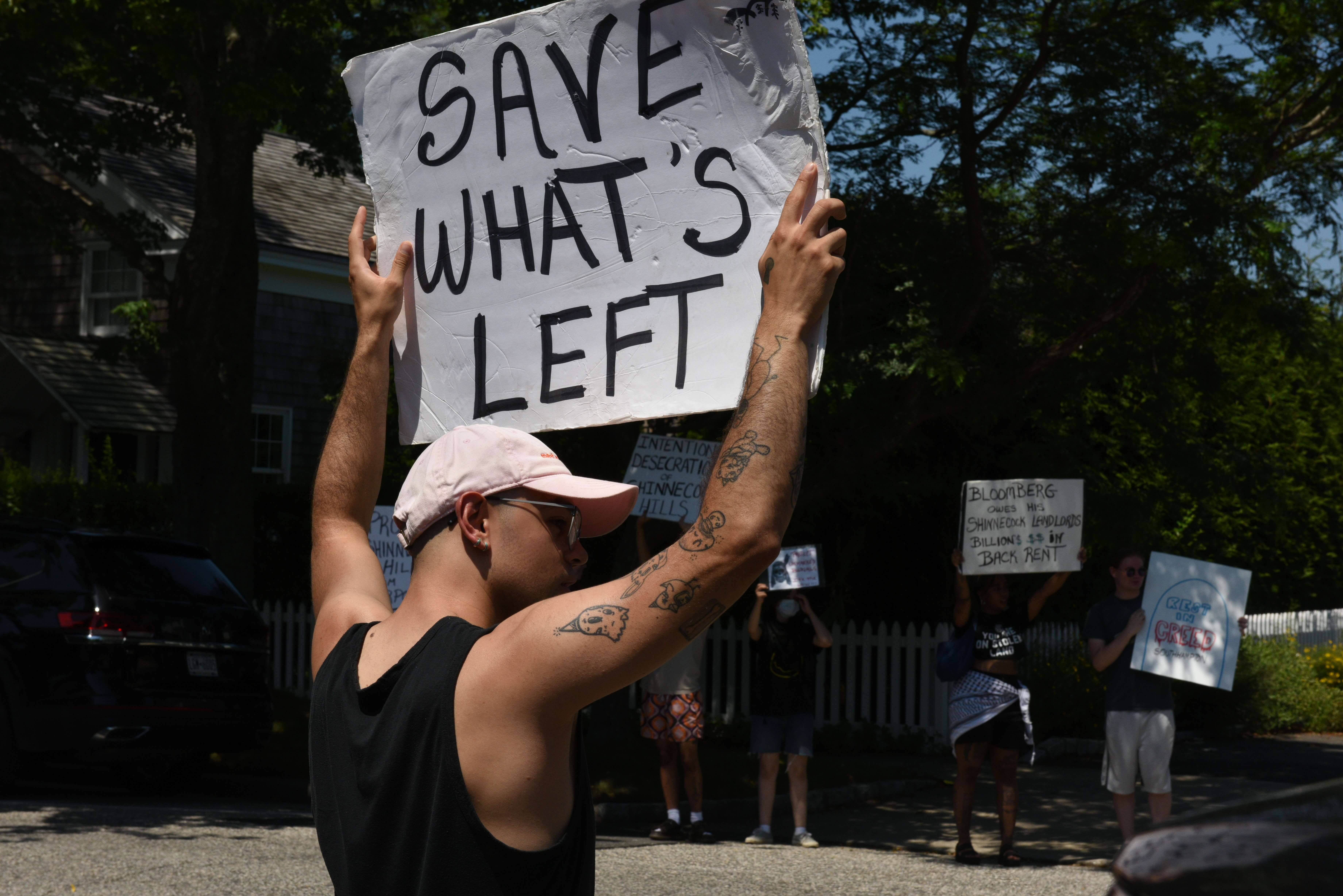

The Shinnecock Graves Protection Warrior Society — a group that aims to stop real estate developers that build on land where the remains of the tribe’s ancestors are buried — rallied to urge the Town of Southampton to use the Community Preservation Fund to preserve more of the tribe’s ancestral land in Shinnecock Hills. Protesters banged drums, chanted and picketed with signs outside of town hall to raise attention to their cause.

“Defend the Sacred,” “Save What’s Left,” “Rest in Greed: Southampton” and “This Indigenous Woman: I’m Done,” read some of the signs that the Shinnecock protesters — who joined forces with Climate Defenders for the rally — carried in their march on town hall.

In 2021, Southampton spent $5.3 million in CPF funds to acquire a 4.5-acre plot of land known as Sugar Loaf Hill, which the Shinnecock consider sacred ground where tribal ancestors were buried thousands of years prior but had a mansion built on top of it. But the Shinnecock GPWS is urging more Shinnecock land be saved from developers’ bulldozers — arguing that there has been insufficient use of CPF funds to prevent what the group calls the ongoing destruction and desecration of Shinnecock Hills, which now ranks as some of the most prime real estate in the nation.

“Purchase, preserve and protect these hills for the right reasons,” said Rebecca Genia, cochair of the Shinnecock Graves Warrior Protection Society. “It will stop desecration, overdevelopment and animal killing, and improve water quality.”

Environmentalists who rallied alongside the Shinnecock added that overdevelopment on the East End has also contributed to increased pollution and decreased water quality.

“It is our responsibility as climate activists to stand in solidarity with the Shinnecock Nation and protect the eastern shore,” said Ravi Zahari-Brunner of Climate Defenders.

The CPF program that the activists called into question was established a quarter century ago this year. It established a 2% real estate transfer tax on East End property sales, with the five Twin Forks region towns able to tap into the fund to acquire open space and save it from development. Outgoing New York State Assemblyman Fred W. Thiele Jr. (D-Sag Harbor) championed the creation of the CPF, which has accrued over $2 billion since 1998.

“I fully support the Shinnecocks in their efforts to dedicate more CPF funds to protect Shinnecock aboriginal lands,” Thiele told Dan’s Papers. “In fact, there is an amendment to the CPF Law that passed the (State) Legislature this past session on this subject that is currently awaiting action by the governor.”

The amendment clarifies that the CPF program could be used for “preservation of lands that contain significant cultural resources including the aboriginal lands of indigenous peoples, including but not limited to, burial sites, settlements, and lands utilized for ceremonial purposes,” the text of the legislation reads. Gov. Kathy Hochul has until the end of the year to either sign the amendment into law or veto it.

Many in the Graves Protection Warrior Society counter that the CPF does not represent genuine support, which is why they felt the need to protest outside Southampton Town Hall.

“We have no implicit control over the money designed to help us,” said Jennifer Cuffee-Wilson, a recovery coach of the Shinnecock Nation.

The protesters were heard by those inside town hall.

Southampton Town Councilman Michael A. Iasilli, who is the town board’s liaison to the Shinnecock Nation, noted multiple grants for community and economic development. He recently enacted legislation that dedicated October 10 as Shinnecock Heritage Day, supported youth and senior programs and leveraged community preservation funding for the repair of vulnerable Shinnecock homes and land preservation.

“The CPF is dictated by state law, but can be used to benefit the nation’s interest,” said Iassilli. “Southampton is less populated … thanks to the CPF’s service as a bulwark against overdevelopment.”

The advocates maintain that there is still much work to be done to undo centuries of injustice that have marginalized indigenous communities. The protestors noted that in 1703, town officials offered the Shinnecock a 1,000-year lease on 3,600 acres of land in Shinnecock Hills but later broke that lease by falsifying records in 1859, according to allegations the tribe has made in court.

Some of that disputed land is now Shinnecock Hills Golf Course and Stony Brook University. The Shinnecock Nation territory today is about 800 acres, or 1.3 square miles.

Rueben Genia, brother of Rebecca Genia, said the land was taken using foged indigenous leader signatures.

“The Claflin estate, which turned into Southampton College, was an acreage sold through the abdication of our contract in 1859,” he said. “Mr. Claflin bought 600 acres of newly acquired Indian land, according to their own records. We take all our information from town documentation.”

He added: “Egregious damage was done to burial mounds during the construction. This was all documented in their town hall.”

The protestors questioned whether they really have the town’s ear when moneyed interests in the playground of the rich and famous often speak louder.

Genia asked, “Why should they listen to a bunch of poor Indians when they have the wealthy to listen to?”