Shinnecock Citizens Rise in Science & Environmental Advocacy for the 7th Generation

In recent years, the Shinnecock Indian Nation has gained significant attention in the realms of science and environmental policy, thanks to the achievements of its next-generation academic citizens. Among those at the forefront of research are Dr. Sierra (Wiegman) Brown, Kelsey Leonard and Joshaya Trotman.

While many readers have just returned to the grind of fall work and “back to school” after a summer in the Hamptons, it’s a fitting time to highlight some of the recent work these accomplished young women are doing in academia and climate advocacy. Their ability to integrate our Indigenous Shinnecock knowledge with modern scientific practices at work is unique. All three are working on research that illuminates critical environmental and health issues around the natural world. These support our Indigenous belief in creating a better world for the “seventh generation,” or seven generations coming after us.

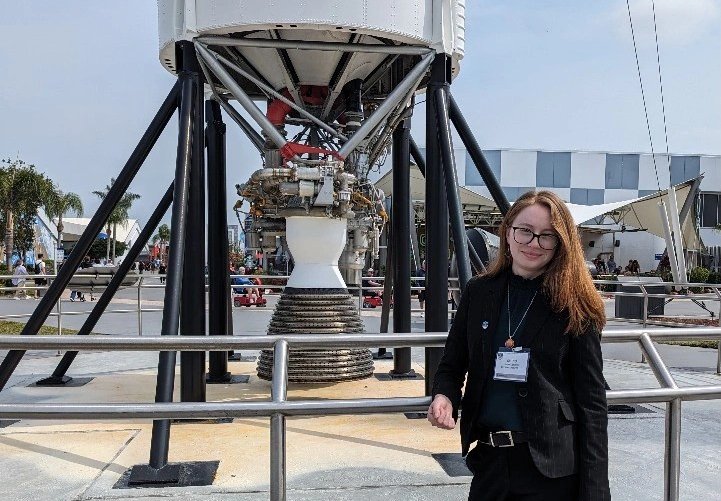

Sierra Brown, an alumna of SUNY Fredonia, where she received her bachelor’s degree, and Brown University, where she earned her Ph.D., who grew up on the Shinnecock Indian Reservation, combines planetary science study with Indigenous environmental policy studies. She’s always been enthusiastic about environmental stewardship, she notes. “My grandmother fondly recalls the garden I set up to ‘save the monarch butterflies’ when I was in elementary school and my mother rather sourly recalls the number of rocks I put through her washing machine to ‘get them clean’ when collecting them.”

In high school, Brown took an astronomy course in an effort to be able to “see the pictures everyone else saw” in the sky – constellations. “Spoiler alert,” she jokes. “The constellations don’t really look very much like what they’re ‘supposed’ to be. However, in that course I was able to go deeper into the content with independent studies with the professor and decided I’d like to work for NASA.”

The resourceful young woman then searched the alumni directory at her university, Fredonia, and found someone who worked for NASA. She cold-called him to ask what to major in. “He told me that ‘you have to know your own planet before you can know others,’ and so I majored in geophysics and geochemistry.”

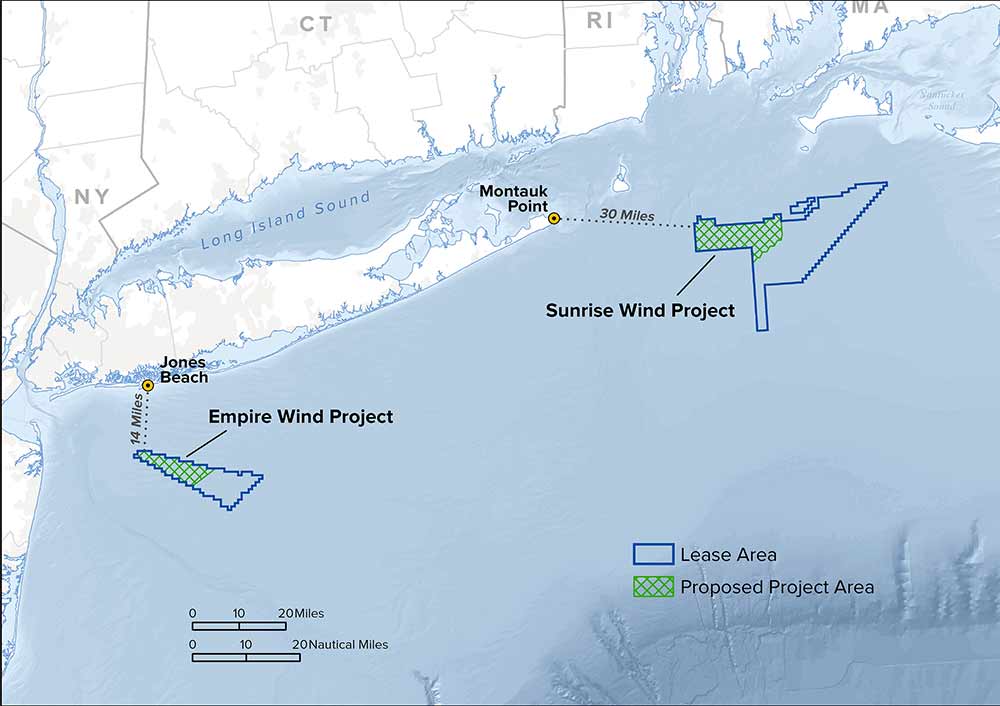

Years later, Brown not only works for NASA, but also does some elite research projects related to our Shinnecock homelands through her new company, Two Worlds Scientific. One such project, she says, “develops a way to measure the reflected wave energy within Shinnecock Bay to investigate the concerns that bulkheading of shorelines have increased the intensity of waves hitting Shinnecock’s coastline. Another looks at creating a GIS visualization tool that integrates traditional Shinnecock knowledge with data from NASA and other publicly available data from government agencies.

“This tool would be co-developed with the community,” she adds, “and used to make actionable decisions regarding environmental equity and justice potentially about various topics such as solar panel placement, water quality monitoring and land reclamation targets for future migration necessary due to rising sea levels.”

Environmental concerns of the Shinnecock Nation are always front of mind for Brown, who spends a lot of time thinking about her homeland and how to remain focused on its needs. In graduate school at Brown University, she earned an M.S. and Ph.D. in earth, environmental and planetary sciences. While her doctoral research was groundbreaking, focusing on the geochemical modeling of the Martian surface and contributing to several NASA missions, Brown realized she needed an intentional tie to home.

“The further I got through [graduate] work, the more I realized that I felt disconnected from my culture and needed to be able to integrate it to feel authentic,” she recalls. “So here I am today, trying to do just that: integrate indigenous knowledge with a western scientific education and put that work to use to benefit our community.”

The Indigenous practice of “two-eyed seeing,” which combines Indigenous and Western ways of thinking and acting, helped to inform her role as principal investigator of a NASA “Transform to Open Science Training” grant, “Knowing the Sky: Building Open Science Skills through Native Knowledge Practices.” This initiative aims to foster open scientific practices that honor and incorporate Indigenous worldviews and helped her win the NASA Space Tech Catalyst Prize for her efforts in supporting underrepresented groups in space technology development. Brown continues to focus on developing software tools to empower Indigenous tribes in their environmental justice initiatives.

A fellow Shinnecock citizen, Kelsey Leonard, is an active and passionate advocate of Indigenous water justice, with impressive academic degrees: an A.B. from Harvard University, an M.S. from the University of Oxford, a J.D. from Duquesne University and a Ph.D. from McMaster University, and more credentials. Leonard is a water scientist, legal scholar and policy expert whose research concentrates on Indigenous water justice, a key part of creating governmental environmental policies that help support and heal our mother earth.

Leonard argues often that “there cannot be Land Back without Water Back,” referring to the international Indigenous #LandBack movement and advocating for Indigenous sovereignty over water resources. She was named one of the “30 Under 30” world environmental leaders and received the “Native American 40 Under 40” award. Her 2019 much-watched TED Talk, “Why lakes and rivers should have the same rights as humans,” helped make Leonard an increasingly prominent voice in water rights and environmental ethics spaces.

Growing up on our coastal ancestral lands at Shinnecock, Leonard found a passion for water as a living being capable of carrying stories – as our ancestors believed. Travel to Samoa during college led to further study at Harvard and other universities, like the University of Waterloo, where she is the Canada research chair in Indigenous waters, climate and sustainability. Roles with the Mid-Atlantic Committee on the Ocean and the National Ocean Protection Coalition Science Advisory Team keep Leonard closely connected with efforts in environmental planning.

An emerging talent in biotechnology, Joshaya Trotman of the Shinnecock Nation is an associate scientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai with a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biotechnology from Brown University. There, Trotman conducts research on the role of NRP1 in biliary fibrosis, and more broadly, she looks at diseases that affect liver function.

The success of Indigenous scientists – notably all women – like Dr. Brown, Dr. Leonard and Joshaya Trotman is encouraging. With the strength of their passion and commitment to solving environmental and epidemiological challenges, younger generations of Shinnecock and other tribal communities can see possibility in STEM careers for themselves. Their work also helps emphasize the importance of creating a new paradigm in scientific research, one where traditional ways and ecological knowledge coexist with scientific inquiry.