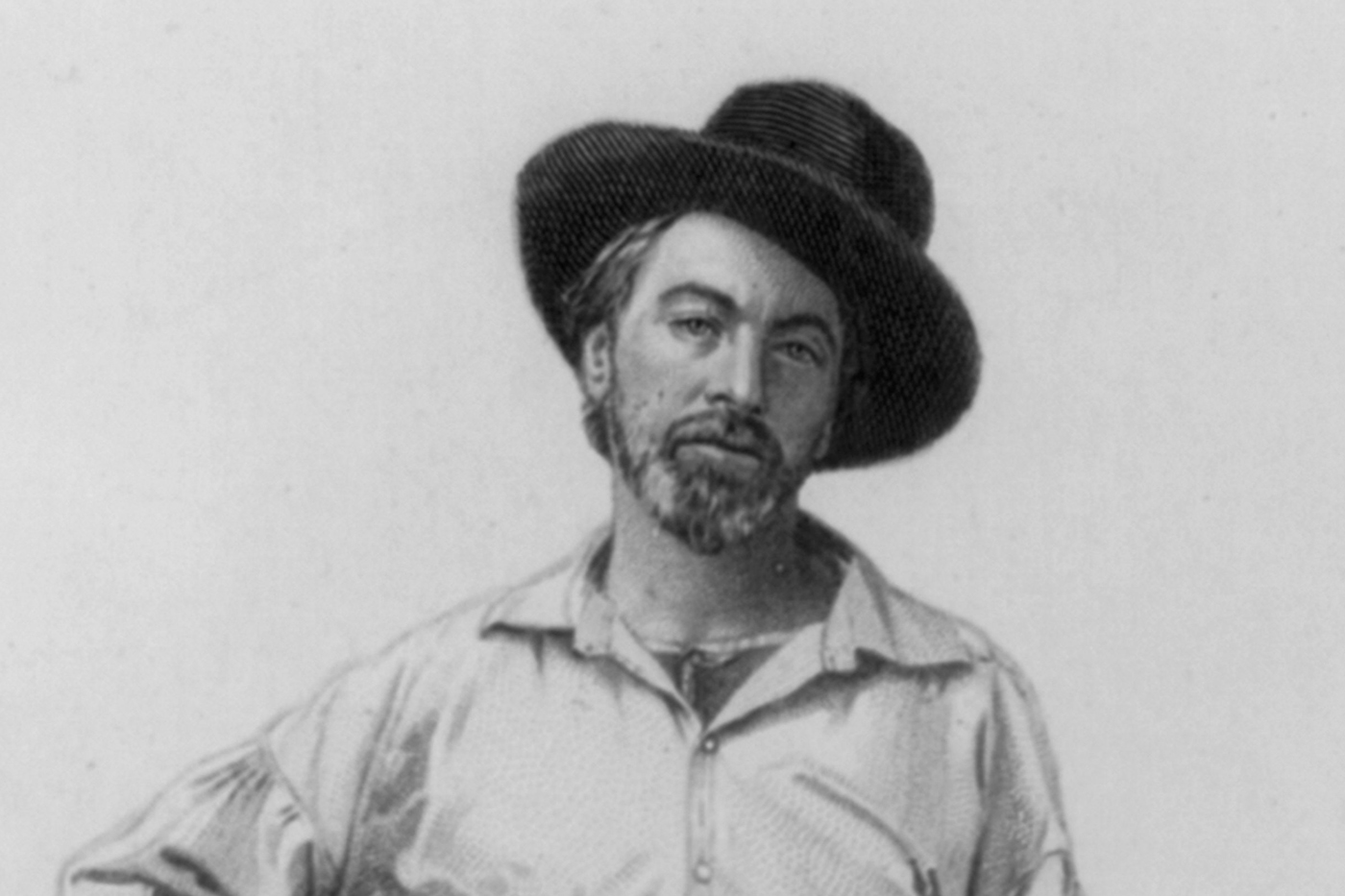

East End Myths: Was Walt Whitman Tarred & Feathered in Southold?

The little villages on eastern Long Island, built at the same time as early English settlements in New England, still display town greens and ponds, old English windmills, churches and cemeteries.

There’s a rich history here. Captain Kidd buried treasure here. Teddy Roosevelt and his Roughriders came. Thomas Edison fiddled with electricity, Albert Einstein spent summers in Southold and Jackson Pollock created a new art form in Springs.

Also here was America’s greatest poet, Walt Whitman. He was 35 when he wrote Leaves of Grass in 1840. Fourteen years earlier, at 21, he taught the kids of Southold in a one-room schoolhouse here. It’s said his time ended violently when citizens, charging him with sodomy, tarred, feathered him and drove him out of town.

When I arrived here as a teenager in the 1950s, I was shocked to hear this old schoolhouse called the “Sodom School.” Back then, a sodomite was someone who engaged in prohibited sexual activities.

I thought this could not be so. And it’s turned out, no evidence ever confirmed that Whitman’s violent eviction ever took place.

That same year I arrived on the East End, a graduate student named Katherine Molinoff wrote a Master’s thesis at CW Post College about Walt Whitman at Southold. Driving to Southold, she interviewed members of 50 families living here who each told her nearly identical stories about events they’d been told by their grandparents, who’d heard it from their grandparents. Here’s what was said.

Young Walt Whitman’s essays were being published by newspapers in Manhattan and on Long Island. He was against slavery and corruption and in favor of anything that celebrated life. As his essays did not make much money, he also worked as a school teacher. In 1840, he was hired to teach school at the Locust Grove School, a one-room schoolhouse in Southold. At this time, it was common practice for communities to hire enthusiastic and well spoken young men and women to teach their kids the ABCs. Hired for a semester, they’d be paid a stipend and given lodging and meals in the home of one of the families in town. They’d sleep in the attic, often with their students. They’d be friends, role models and mentors to the children. That semester, Walt Whitman stayed at the home of Mr. and Mrs. George Wells, who had two children.

Locally, Whitman’s passionate essays appeared in the Greenport Republican Watchman. Whitman opposed slavery, still in effect in the South and elsewhere, and he opposed Teapot Dome corruption in Manhattan, where palms got greased at Tammany Hall. He was in favor of life, fun, the mysteries of the universe and the beauty of everything natural on the planet, and he wrote freely and easily about whatever was on his mind. Here is a passage from a letter he wrote to one of his bohemian friends back in New York City. It’s confirmed he wrote this. And though it was never a column, it gives you the idea of how Whitman thought and wrote.

“I am sick of wearing away by inches and spending the fairest portion of my little span of life here in this nest of bears, this forsaken of all God’s creation; among clowns and country bumpkins, flat heads and course brown-faced girls, dirty, ill-favored young brats, with squalling throats and crude manners, and bog trotters, with all the disgusting conceit of ignorance and vulgarity.

“Send me something funny, for I am getting to be a miserable kind of dog.”

One Sunday, according to these reports, Ralph Smith, the pastor of the Southold Presbyterian Church denounced this 20 year old, calling him a Sodomite. Walt Whitman should be run out of town. Forcibly.

An angry mob assembled outside the church and headed toward the home of Mr. and Mrs. George Wells, stopping along the way to climb Kettle Hill, where fresh hot tar was heated over a fire and available to any farmer or fisherman for free for whatever purpose intended.

Hearing of their approach, Whitman fled the Wells home and hid in the attic of a home nearby owned by Dr. Ira Corwin. But Whitman was tracked down, held, tarred and feathered, and then was headed out of town until a woman named Aunt Lina arrived and demanded Whitman be let go into her care. The mob retreated, she attended to his wounds for a month then secreted him out of town never to return.

Though no records in Southold confirm this ever took place, some historians are convinced, persuaded by this community word of mouth, that it happened.

Read more of Dan Rattiner’s stories.