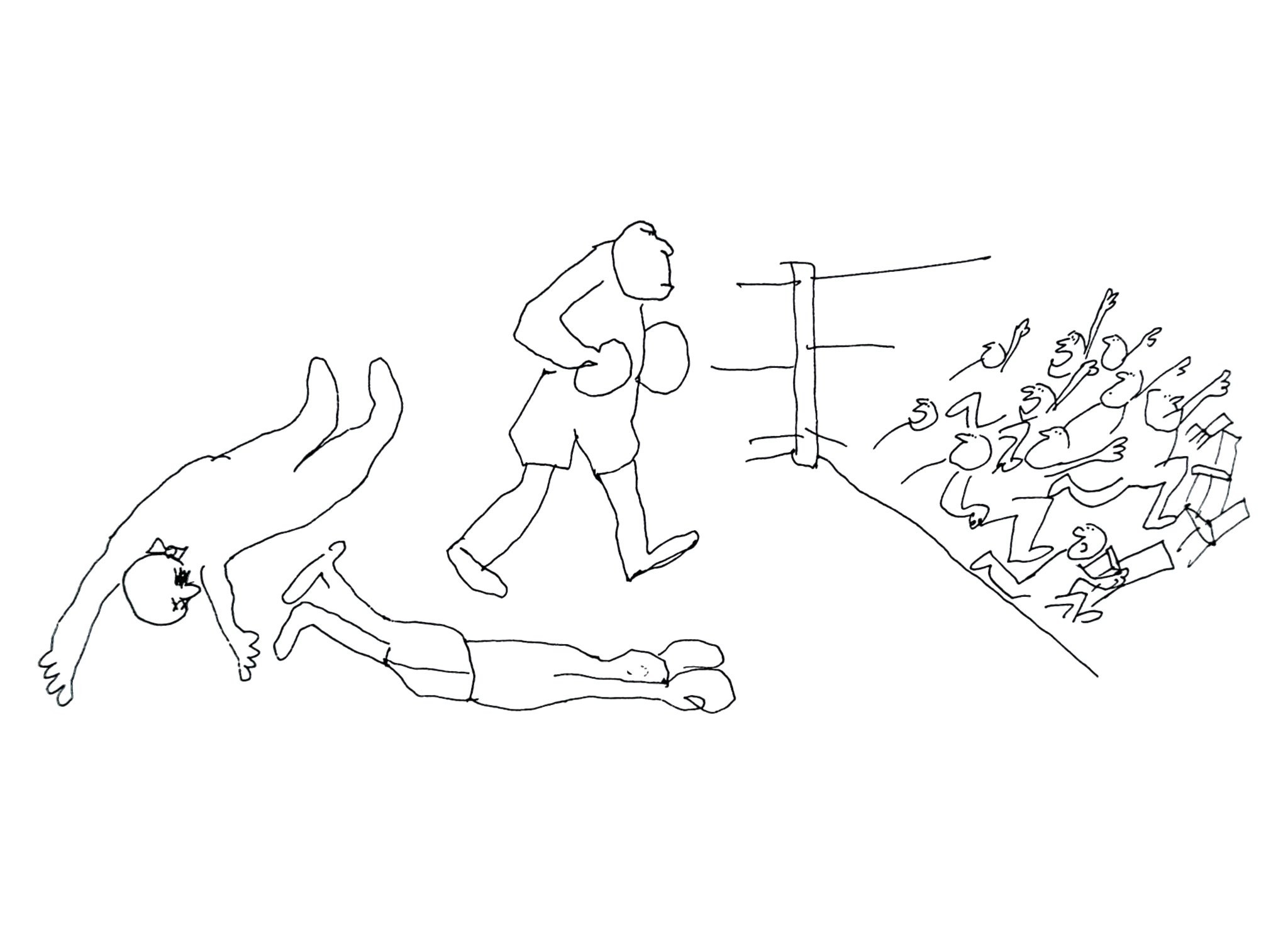

The 501c3 Smackdown at Conscience Point

In the red corner, incorporated in 1910 as a non-profit corporation that subsequently secured interest in part of a 5-acre property at Conscience Point where the first English settlers in New York landed in 1640, I present the Southampton History Museum.

And in the blue corner, founded in 2013 as a non-profit corporation and now the sub-tenant on part of the History Museum’s Conscience Point property where the first settlers landed in 1640 is the challenger, the Conscience Point Shellfish Hatchery!

Please come to the center of the ring.

It is rare to see two non-profit organizations, one raising oysters and clams to replenish the species and the other celebrating and teaching visitors about how English people got here, now getting it on.

They’d been friends as tenant and sub-tenant next to one another for years. In more recent years, not so much.

Things came to a head on November 30. But it really began on October 30 when the shellfish hatchery received a lawyer’s letter from the Southampton History Museum that 30 days after this letter was sent, the shellfish people’s lease would be at an end.

“It has come to SHM’s attention that CPSH has been conducting commercial operations from the premises, has sublet the premises to commercial entities – and has allowed these entities to conduct commercial activities from the premises,” it read. “SHM demands that CPSH immediately cease and desist from conducting any and all commercial activities from the premises and immediately cease any sublet activites. Based upon CPSH’s ongoing violation of the lease, the board of trustees of SHM has voted to terminate the lease effective November 30, 2024. As such CPSH is required to vacate and surrender possession of the premises to SHM on or before the termination date.”

From what I am told, a hatchery is where humans encourage a species to propagate, thrive and get itself scattered out into a bay by the humans. What is, instead, happening here, is that in addition to doing that, the humans have allowed two commercial fishing boats to tie up at the hatchery’s dock, have their captains pay rent to the hatchery, and then sell oysters and clams to local restaurants and fish stores. One place mentioned as a recipient of shellfish is the exclusive Southampton Beach Club on Meadow Lane where wealthy club members can eat their lunch, sunbathe and swim in the ocean in the summer time.

Furthermore, the property being rented to the hatchery has become a mess. Trash is everywhere. There’s fish buckets and parts of ship engines, rags and beer cans and such.

In this, the first round since the bell sounded on November 30, the hatchery people have been sent reeling. They agree it’s a mess. They agree they should have asked the tenant ahead of time if they could sublease dock space to fishing boat captains who sell clams and oysters. And they have vacated the premises. Or have they? Actually, they’ve lawyered up.

The law says that tenants may continue to stay in possession while they fight an eviction notice. I know this from personal experience. Long ago, when I started Dan’s Papers at age 20, I moved out of my parent’s home in Montauk only after finding a quirky rental situation in East Hampton. It was a small cottage South of the Highway for rent for not much money. I didn’t have much money. But it was being offered as a summer rental by a husband getting a divorce from his angry wife. He prevented her from staying there. And she prevented him from staying there. So nobody was staying there. However, the husband agreed that if I wanted to pay his mortgage for him – she was paying none of it – and risk having his wife evict me, I could go right ahead. And so I did. I paid the June mortgage of $63.42, moved in, and when she arrived in a rage to evict me I’d already done what my lawyer told me. Change the locks and don’t let her in. Give her my lawyer’s card. He would then hold her off until September. So I did that. It was not pretty. But that fall, after paying almost nothing for the summer, I bought the place. My first home.

Anyway, on the leased property, the shellfish people have, with the approval of the landlord, expanded a small shed by the dock into an office and welcome center, where visitors could see literature and photographs on how the oysters are raised in the hatchery.

Meanwhile, Southampton Town gives walks through the property to the general public. On these walks they encounter the boulder upon which is affixed an iron plaque explaining that the first person coming down the plank in 1640 was a woman who said “for Conscience Sake, we’re on dry land.” This was a reference to their beliefs. They were from Lynn, Massachusetts and they’d fled to a new place because they were being persecuted by other residents of Lynn for believing a different kind of Christianity than they did.

Elsewhere on this property owned by the Town is a large boathouse, built in the early twentieth century by a man name Tupper. Long after he was gone, the boathouse, still standing but abandoned, became a late night disco called L’Oursin. I loved it and went there several times. There were live bands, flashing lights, smoke, alcohol, etc. etc. I recall dancing one night – just one dance – with a young woman wearing nothing but a see through clear plastic dress. When the music ended, I smiled. But she ran off.

Years later, this disco was where Lizzie Grubman, a NYC publicist in a Mercedes her daddy gave her, got angry about how the bouncers were making her park and go to the back of the line to get in, put her car in reverse and ran over some of the would be patrons before roaring off in a huff.

This was such a sordid affair – nobody died however — that the nightspot was closed, leaving the town to announce their intention to restore the boathouse (at a cost of $10 million) and make it a marine museum like the one we have in East Hampton. The Town arranged with a non-profit called the North Sea Maritime Center to make that happen. This entity, another non-profit, has no connection with either the Shellfish hatchery or the Southampton History Museum.

It’s just that the Southampton History Museum doesn’t want all this crap next door at the Shellfish hatchery.

Can’t they all just work this out?