Art Walk: Explore the Renee & Chaim Gross Home/Studio in NYC

Nestled in an unassuming building on a tree-lined street in Greenwich Village is a dinner-party-worthy home studio that epitomizes a fantasy New York art world that, if it ever existed, no longer does, yet we can’t seem to stop searching for.

The historic townhouse of Renee Gross and her husband, sculptor Chaim Gross (1902-1991), spans three spacious floors. It now houses the Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation, which offers public tours. The ground floor features a sculpture studio and an adjacent gallery showcasing work from Gross’s seven-decade career. The narrow stairwell is packed with unevenly hung paintings, leading visitors to a temporary exhibition space currently hosting the show Art for All: Innovations in Twentieth-Century Printmaking. The top floor, which served as the main living area, presents a dizzying mishmash of the couple’s remarkably varied collection.

In 1963, the Grosses converted a former art storage warehouse built in the 1830s into their home and studio. The Foundation was first established in 1974. Comprising over 12,000 objects, the Foundation’s collection includes Chaim’s sculptures, drawings, and prints; a photographic archive; and the couple’s extensive collection of African, Oceanic, Pre-Columbian, American, and European art that remains installed in the townhouse as the Grosses originally arranged it.

Chaim, the youngest of ten children in a Hasidic family, was born in 1904 in Máramaros County, Kingdom of Hungary, in the village of Ökörmező (now known as Mizhhiria, Ukraine). The family fled to Kolomyya during World War I, returning briefly in 1915. Shortly after, Chaim moved to Budapest to pursue an arts education, then to Vienna a year later. Eventually, he settled in New York and continued his artistic pursuits at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design. He remained in New York for the rest of his life, although he was also an active member of the arts scene in the gay refuge Provincetown.

Renee was born Rebecca Nechin in 1909. After World War I, she immigrated with her family to New York City from Lithuania and studied literature at Brooklyn College. In the 1930s, she met Chaim. They married and had two children: Yehudah, an engineer, and Mimi, an artist.

Chaim began his journey working in two dimensions but quickly realized his preference for three. He was an early adopter of direct carving, a technique where the process informs the final object instead of relying on a meticulously planned model. While bronze and alabaster works populate the ground floor studio and exhibition space, Chaim appears to prefer wood, often carving into blocks of exotic hardwoods like lignum vitae, a wood from South America.

Circus imagery recurs throughout Gross’s sketches and carvings: acrobats dangle from each other’s lithe limbs, dancers balance on narrow pedestals, and a child rests effortlessly on a larger figure’s outstretched hand. His forms, many of which echo the African works displayed in the living quarters upstairs, are influenced by African techniques and aesthetics.

Mother and child figures also punctuate the studio and gallery, reclining peacefully in each other’s arms in alabaster or wrestling playfully in bronze.

His career extended well beyond the studio. Chaim was a longtime educator, with a five-decade tenure at The Educational Alliance beginning in 1926, where he taught Louise Nevelson, many of whose paintings adorn the walls of the Gross home. In addition to arts education, Chaim was also a member of the New York division of the Public Works of Art Project and the founder of the Sculptors Guild. In 1957, he published a book titled The Technique of Wood Sculpture.

Chaim’s studio on the lower half of the split-level ground floor is delightfully chaotic. Work tables, vertical files, and projects in various stages of completion line the perimeter of the room; brushes, sketches, tools, and assorted objects cover every surface; a custom-built floor made of three-to-four-inch wood blocks unfolds in an even grid across the space; a sloped skylight allows blue winter sunlight to filter in.

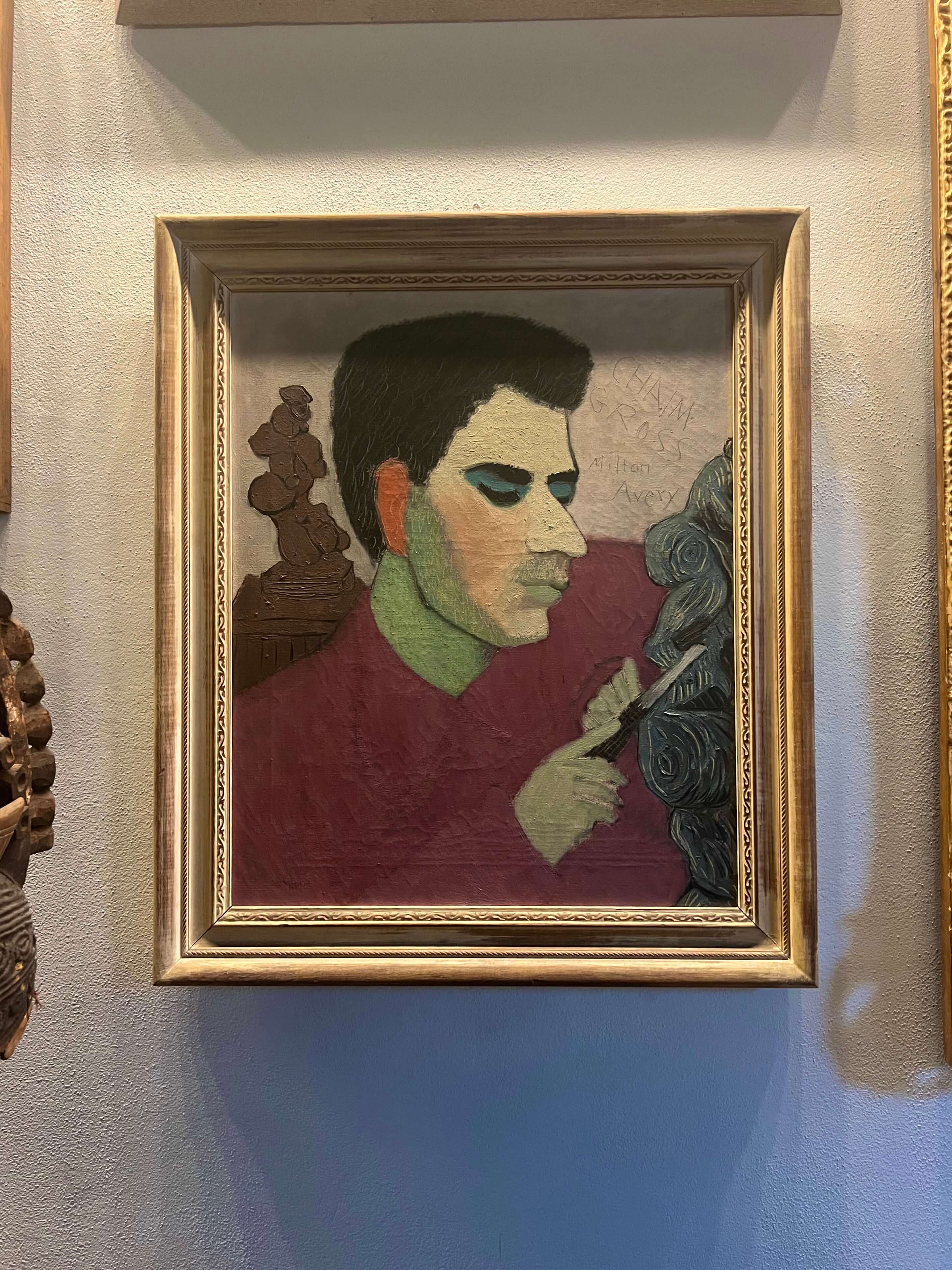

The top floor feels lived-in, to put it nicely, yet it remains markedly static compared to the vibrancy of the studio. Dark wood furniture, upholstered in faded burgundy velvet, fills the dimly lit living room; paintings stacked one atop another in heavy gilded frames line the gray-yellow walls. Multi-textured African masks preside over the chaos. As my eyes adjust to the onslaught of colors and styles, an unexpectedly queer-coded Milton Avery portrait of a young Chaim—complete with blue-shadowed eyelids and a plum-hued shirt—jumps out at me. With such an extensive and varied collection, the curatorial possibilities are endless. Yet, the Grosses’ primary goal appears to be cramming as much onto the walls and surfaces as possible.

Like the living room, the dining area is adorned with framed artworks of various sizes and mediums (a Willem de Kooning presides over the head of the table). As one circles the long wooden table and surveys the clutter of books along the wall, it becomes evident that the Gross residence was once vibrant with interactions and events—one can’t help but wonder who would have found themselves with a seat at the Gross dinner table.

The European and American collection features works by renowned artists such as Max Ernst, George Grosz, Pablo Picasso, Milton Avery, and Willem de Kooning, along with Renee and Chaim’s daughter Mimi and many of their friends. In the grand, salon-style space, everyone is given equal regard. There is a certain comfort in seeing a life frozen in time.