Hamptons Soul: The Bigger Picture of Philanthropic Giving

In this edition of Hamptons Soul, Rabbi Josh Franklin of Jewish Center of the Hamptons and Reverend Ben Shambaugh from St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, both in East Hampton, discuss philanthropic giving from the perspective of their faiths.

By Rabbi Josh Franklin

Sir Moses Montefiore, the 19th-century Jewish philanthropist, was once asked about his net worth. He gave a number far lower than expected. When challenged, he explained, “You asked what I’m worth. I’m only worth what I have given away.”

This perspective — radical in today’s world — is at the heart of Jewish wisdom. While conventional financial advice tells us to save and accumulate before giving, Judaism teaches the opposite: give first, and abundance will follow.

The Talmud (Shabbat 119a) explicitly links giving to prosperity, teaching that Jews in the Land of Israel were wealthy because they gave tzedakah (charity). Maimonides, the great medieval Jewish philosopher, reinforced this idea: “Anyone who gives tzedakah will never be poor.” At first glance, this seems counterintuitive. If you’re struggling financially, the logical approach is to hold onto every dollar, not give it away. And yet, Jewish tradition insists that generosity leads to greater wealth—not just spiritual wealth, but actual financial stability.

This principle goes beyond finances — it’s a mindset shift. In Jewish thought, wealth isn’t defined by what you accumulate but by what you share. The Kabbalists describe a divine flow, shefa, where blessings increase when we keep generosity in motion. Think of it like a pipeline: the more you let resources flow through you, the more you receive. But if you hold onto everything tightly, the pipeline clogs. Giving is what keeps it open.

It’s easy to dismiss this as a lofty spiritual ideal, but Jewish history proves otherwise. Despite centuries of hardship and exile, Jewish communities have thrived by prioritizing communal responsibility and philanthropy. Whether donating money, time, or expertise, giving has remained central to Jewish life.

It’s a countercultural way of thinking, but one that has stood the test of time. So, if you’re looking for real abundance, try something bold: give more. It might feel risky, but Jewish wisdom suggests that the more we give, the more we create a world of blessing — for ourselves and for others.

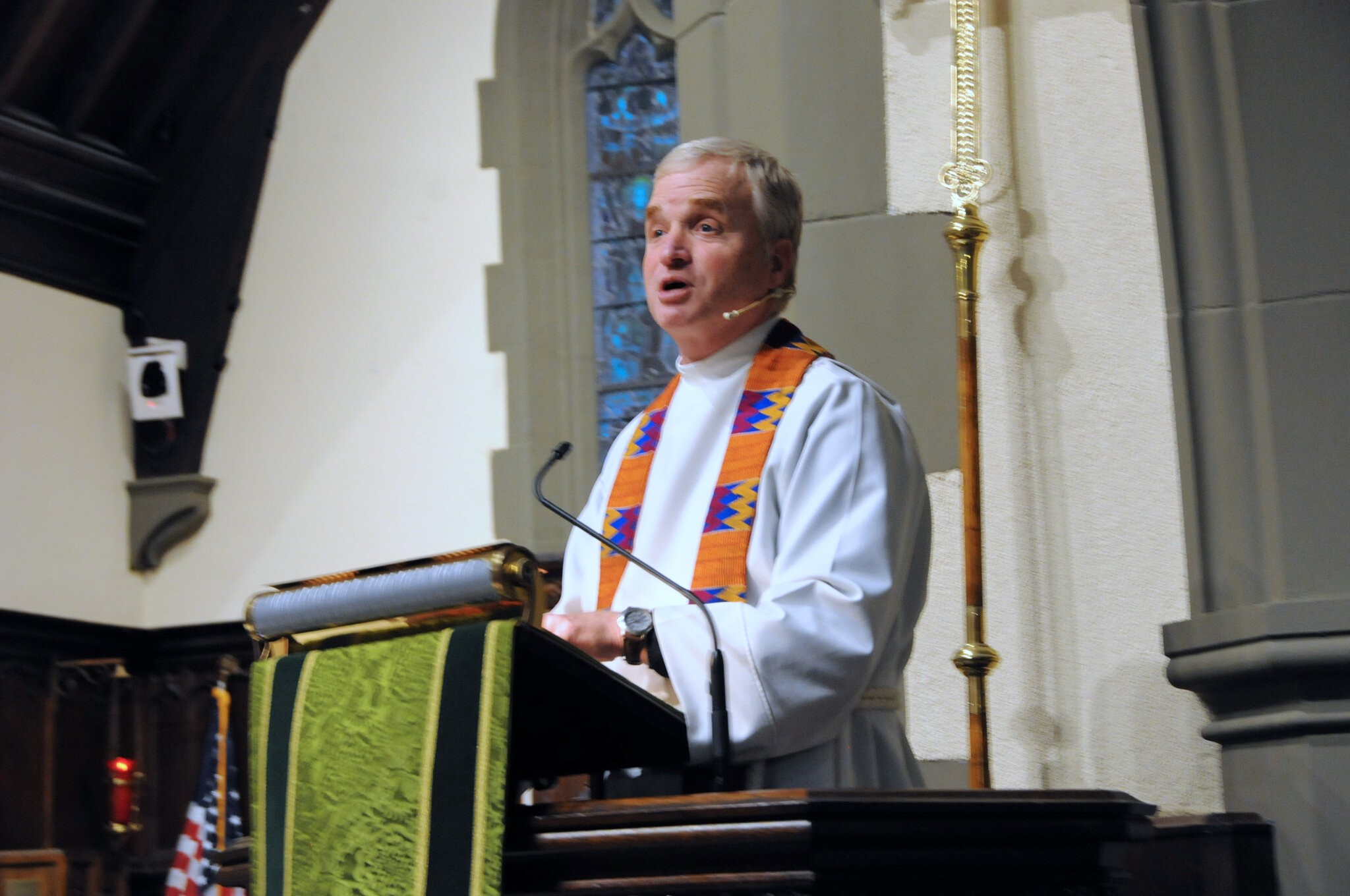

By Rev Ben Shambaugh

Consider, for a moment the “economic halo” of a faith community. An economic halo is the impact an organization has on the local economy. Most people don’t realize that beyond functioning on spiritual, educational, cultural and service levels, congregations also serve as economic generators, small business incubators, and leadership training centers for their local communities.

Partners for Sacred Places and the University of Pennsylvania conducted a study that showed that the average urban sacred site generates an economic impact of $1.7 million for the local community, with many generating even more. Imagine, for example, a congregation that has ten weddings a year, each of which bring in more than 100 people from out of town, all of whom spent at two nights in local hotels, buy food at local restaurants and shop at local stores.

Do the same the same calculations for an even larger number of concerts, baptisms, funerals and other events. If you add to this the less visible but even greater impact, for example of a person, who keeps his job because of attending AA meetings or stays married because of counseling or support or develops self-confidence and leadership skills because of participation in congregational life, the economic halo is huge. That doesn’t even touch congregation’s donations in finances or in free or reduced cost physical space, or the giving to the community of time, talent, and treasure by congregational members whose philanthropy was inspired by their faith. It also doesn’t mention the future and present impact of young people raised up in a faith community or the way that churches provide mentoring and job possibilities to those re-entering the work force after a period of struggle or unemployment.

Taxing congregations and other non-profits threatens their viability, and their loss would be expensive in more ways than we can imagine. We should not be taxing them. We should be thanking them instead — and doing what we can to help them thrive.

If you get an income tax cut, I have a suggestion: Donate the money you saved to congregation – even one you don’t attend. (If you don’t get a tax cut, consider donating anyway!) They are not only picking up the pieces of programs that have been cut, but they are also helping the economy grow. Consider their economic halo and polish your own.

The Rev. Dr. Benjamin Shambaugh is the rector of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in East Hampton. 631-329-0990 rector@stlukeseasthampton.org